Health insurance has been a hot topic in the nation for a long time. With programs such as the Affordable Care Act, or “Obamacare,” being inconsistent even when available, the healthcare hurdles and the ramifications of an unexpected medical problem are an everyday struggle for many Maricopans.

Ray Nieves, owner/operator of 911 Air Repair, recounted his battle with an insurance company after his oldest son was attacked by their dog. In July 2018, Nieves was on a job in Gilbert when he began receiving calls from his wife McKenzie.

“When I’m with a customer I usually don’t answer the phone. Obviously, we’re trying to maintain professionalism,” Nieves said. “So, I kind of just hit ‘ignore.’”

When a third call came in, Ray answered and received horrifying news — their German shepherd had bitten the head of their 3-year-old son Remy.

“The first responders and everybody showed up before I got there,” Nieves said. “They got him wrapped up, wrapped his head and put him in the ambulance. They were taking him to the children’s hospital in Mesa.”

Remy never lost consciousness, but the doctors determined his skull was fractured.

“They were really concerned with any skull fragments getting into his brain,” Ray recalled. “So, they had to go and do surgery. They brought a pediatric neurosurgeon who went ahead and ensured that there wasn’t anything in there.”

After a few days of monitoring in the hospital and 19 staples, Remy was back to a happy kid, albeit with a shaved head from surgery. Ray and McKenzie decided to shave their youngest son Rayden’s head as well.

“We tried to help him be a little bit more comfortable,” Nieves said with a smile.

Then the medical bills began rolling in.

“[It was] $10,000 for this, $2,000 for that, $15,000 here. It added up very, very, very quickly,” he said.

Nieves described the difficulty in acquiring and providing affordable health insurance as a self-employed, small-business owner.

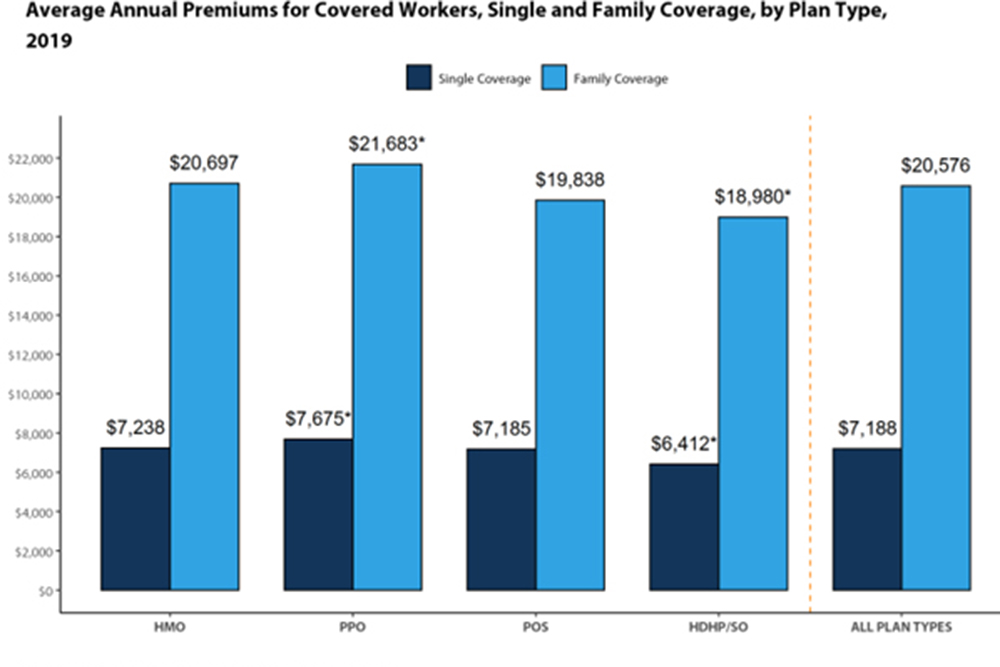

In a 2019 survey published by The Kaiser Family Foundation, small businesses in the United States that do not provide health-care

benefits to their employees still cite the cost as the central reason. The survey reported the average annual premiums as $7,188 for single coverage and $20,576 for families.

“When you are self-employed it’s very difficult to get health insurance,” Nieves said. “It’s kind of like a pay-to-play thing. I’m paying more than my mortgage to have insurance for my family. You know, 1,500 bucks a month to carry insurance that isn’t even the best insurance available.”

“There needs to be reform when it comes to stuff like that, and I just don’t think that anybody’s coming forth with long-term solutions,” Nieves said. “I mean, it’s always been a really touchy subject as far as health insurance and stuff go. To me, it seems that it’s a really bad industry because there’s a lot of money involved. You see what the CEOs and stuff are making, and I’m not against them making money. I mean, that is capitalism, but it’s also a human right.”

Medicaid programs such as Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System (AHCCCS) aim to provide care for low-income households that otherwise would not have insurance. The Census Bureau estimated 4,000 Maricopans — 7.8% of its population of 50,000-plus — were without health insurance in 2018.

U.S. Department of Health data shows 17.4% of children in Pinal County are not covered by health insurance.

Nieves is not hopeful the status of U.S. health care will change anytime soon: “There’s just a lot of stuff that comes into play, and that just goes to show you why it’s such a difficult problem to solve.”

Dr. Philip Wazny, NMD, believes no one knows how to solve the health-care problem, at least not yet.

“Looking at the medical literature, wages and income have not kept up with deductibles,” Wazny said. “It is at the point where patients are not coming in for what may seem like just a cough, now it’s bronchitis or pneumonia.”

Wazny described this lull in people going to doctors in fear of being charged as an “unfortunate rebound” because people could end up with a far more severe ailment if left untreated, oftentimes high blood pressure or diabetes. He said people should be able to choose how they are treated, but with so many big companies involved, it could be quite a while before the nation sees a shift.

“I really think the doctors get paid through the pharmacies, and I really personally do not like doctors,” said Manny Chavez, owner of Prestige Landscaping. “It went from healthcare to a money gold mine.”

He is not in a position to offer health insurance to employees and said they are covered by liability insurance if they are injured on the job. “If the employee gets hurt or not, I’m still paying so much for how many hours they work,” he said. “I still get charged from unemployment insurance, and that’s like the biggest killer to me.”

Health insurance and even healthcare was not a priority when he was growing up, just the work.

“As a Mexican, you were never going to the doctor, and you couldn’t afford it anyway,” Chavez said. “Personally, we were never really supposed to retire. We were supposed to work until our body just quit.”

He said the U.S. healthcare system isn’t necessarily rigged on purpose, “it just happened the way it happened, and everybody’s in each other’s pocket.”

With the Affordable Care Act turning 10 years old, new steps are being made to further solve problems presented to patients in the medical industry. In December, U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions and bipartisan House leaders approved the Lower Health Care Costs Act of 2019.

According to a summary of the proposed legislation by the House Committee on Ways & Means, included in this agreement is the protection of patients and families from surprise billing with a system for “independent dispute resolution often called arbitration.”

These proposals could protect millions of Americans just like the Nieves family who happen to fall victim to the expensive and intimidating health-care system.

This story appears in the March issue of InMaricopa.

![Elena Trails releases home renderings An image of one of 56 elevation renderings submitted to Maricopa's planning department for the Elena Trails subdivison. The developer plans to construct 14 different floor plans, with four elevation styles per plan. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/city-041724-elena-trails-rendering-218x150.jpg)

![Affordable apartments planned near ‘Restaurant Row’ A blue square highlights the area of the proposed affordable housing development and "Restaurant Row" sitting south of city hall and the Maricopa Police Department. Preliminary architectural drawings were not yet available. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/041724-affordable-housing-project-restaurant-row-218x150.jpg)