Robin Holland has an unorthodox family.

One child wears an outfit consisting of fringed, cream leather, accented with real rabbit fur. There are also handloomed ties that ornament her long black pigtails, which peek out from beneath a beautifully colored, beaded headband.

She goes by “Dances with the Wind.”

Another child, known as “Turtle Song,” dons a brilliant scarlet blouse trimmed with ribbon and decorated with silver filigree. Her dark hair is braided and trails behind her, attached to a matching traditional hair piece that evokes fire.

For all their individuality, these “children” share one thing in common: they’re not human.

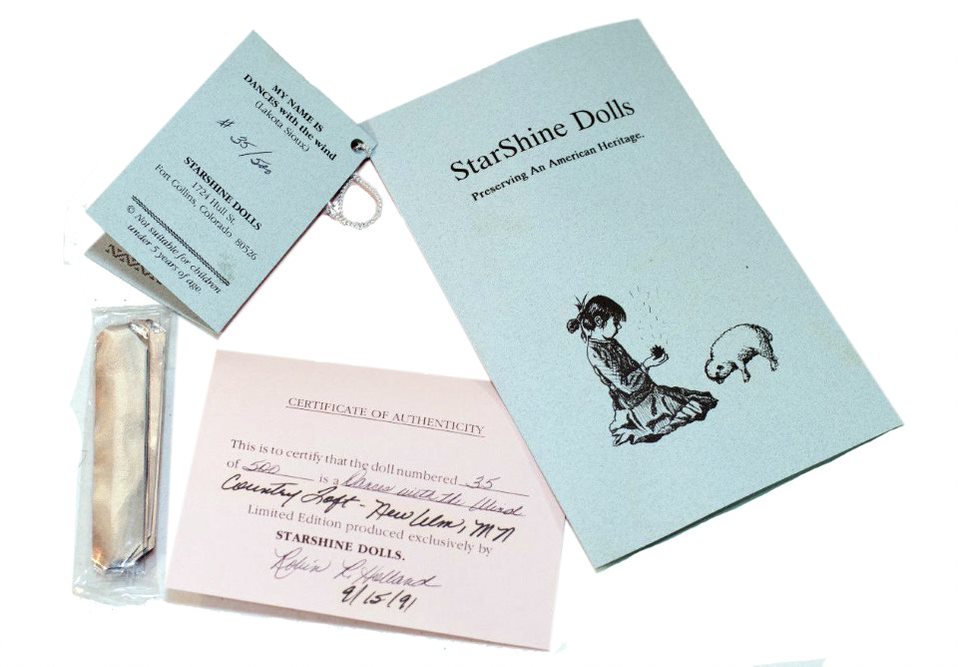

Holland, 69, a Maricopa resident since 2009, was once among the world’s most well-known dollmakers. Her company introduced an innovative line of articulated self-standing dolls called “Starshine Dolls,” which depicted various American Indian tribes in their cultural appearance.

When she wasn’t busy being a mother to five human children, she was busy becoming a mother to children made of vinyl and cloth. About 33 unique Starshine Doll designs were handcrafted by her company in the early 1990s.

But that was then. All things come to an end. And for nearly 30 years, the artist believed her beloved works had been left to gather dust as forgotten playthings of a past filled with success and a good deal of pain.

Little did she know that on the internet, interest was brewing for her Starshine Dolls.

Finding a niche

Holland’s business began by identifying a need.

Seeing the need for a reasonably-priced, yet appropriately-detailed Native American doll, she decided to take matters into her own hands. She took a doll, removed its hair, and put in its place a long-haired modacrylic wig with straight bangs, which she then adorned with Navajo-inspired braids, ties, and a white feather.

Later, she designed a dress and some jewelry to complete the doll’s transformation. Her new name became “Morningstar.”

“I took her on a trip down through New Mexico and I stopped at different doll shops along the way to talk to people and see if they’d be interested,” Holland explained. “And they were all interested.”

When she returned home, she took $2,000 out of the bank and used it to place an advertisement in the November 1989 edition of Doll Reader, a leading magazine for collectors. By the end of the year, she had received over 200 orders.

American Heritage

Holland, an Ohio native raised in New Mexico, has long had strong feelings about Indigenous culture.

“I love the Native American people,” she said. “I think they’re beautiful, and they have been mistreated forever. That’s why I decided to do these dolls.”

In true cottage industry fashion, she converted the loft of her Fort Collins home into a doll studio and immediately began work on the growing list of orders. A special agreement with Götz Puppenmanufaktur allowed her to purchase excess supplies of the German company’s dolls, which arrived at her doorstep bald and undressed. These “naked” dolls were the perfect palette for her creativity.

Morningstar was followed by “Prairie Flower,” a doll representing the Cherokee Tribe. The demand soon required more hands and at its peak, Starshine Dolls employed 15 artisans who helped in all aspects of production. A Navajo couple from Tuba City, Arizona, handcrafted authentic jewelry for every doll, while an expert leatherworker from Lee Leather produced the genuine hide for their costumes and moccasins.

Holland had to quit both her jobs — at the doll store and as a seminary teacher — just to keep up. “I used to sit and sew from eight in the morning to 10 at night,” she recounted. “I worked around the clock to get them out there.”

material was used for the Starshine line — no corners cut, the pamphlets proudly proclaimed. For the beadwork, glass beads were specially imported from Czechoslovakia and worked by hand. Some dolls even have actual moose hair and parakeet feathers.

All the hard work did not go unnoticed. In 1991, her Cheyenne-inspired “Singing Dove” received the prestigious international DOTY (Doll of the Year) award. Starshine Dolls could be found in shops throughout the country, including popular destinations like Busch Gardens and Nashville’s now-defunct Opryland USA. The Denver Post hailed her as “one of the most successful doll makers in the world.”

That all ended in 1993.

Holland had never set out to make money; she simply wanted to help preserve Native American culture in the way she knew best.

Unfortunately, her unwavering commitment to the dolls’ detail and accuracy meant she certainly wasn’t making any money, and in fact, was quickly losing it. A tanking market, as well as the pricey theft of about $6,000 worth of dolls, left her sinking in debt and unable to continue turning her dream into reality.

“I felt like a total failure,” she admitted. “I worked myself to death and then all of a sudden — bam! — nothing. I was so disappointed.”

Just over three years and hundreds of dolls later, the Starshine Doll company closed shop. Holland was forced to take a second mortgage out on her house to work on paying off the bills. The remaining stock of unfinished dolls was given away through programs like Toys for Tots. Slowly, she began to erase the painful dollmaking endeavor from her memory.

In 2009, with her children grown and away from home, she and her husband, Dan, left the Centennial State and settled in Maricopa, putting nearly 1,000 miles between her and the home where her Starshines were born and died.

Rediscovery

Try as she might to forget the dolls, others did not.

In December 2020, she received a call from her son, Adam. “He says, ‘Mom, you’re famous and you’re in Wikipedia and you have a fan club,’” Holland recalled.

Through her son, she learned that her dolls were now some of the most collectible and highest-priced of their kind on the market. One of her original Morningstar dolls, once priced at $249.95, was recently listed on eBay for $999.99, plus shipping. Some Starshines have sold for over $3,000.

“I was just blown away. I thought they went into the black hole of the universe,” she said with a laugh.

Heather Arms attributes this to their painstaking artistry and design.

“Their quality is incredible and evident the moment you see [a] doll in person,” she wrote. “I personally hope one day that Robin [will] know how much Gotz Doll Collectors have come to admire, cherish, appreciate and love the exceptional beauty, design and craftsmanship of her dolls.”

Arms, a doll aficionado known online by her moniker “GotzDollJunkie,” is the creator of the Götz Doll Wiki, a community website dedicated to researching and indexing dolls created by the Götz company. An entire section of the site is solely devoted to preserving Robin’s Starshine Dolls, which have become valued favorites among collectors.

Apart from their intricate detailing and very limited quantities, another factor that has made her dolls so valuable is that their original facial mold is no longer made and thus highly sought after.

Though it was used on other dolls before, its association with her work has led to it being affectionately referred to as the “Starshine mold.”

But when Adam Holland first stumbled across the website, his mother knew nothing of this nor had any idea her dolls were still remembered by anyone. He left an appreciative comment thanking Arms for her effort, and when she replied asking if she might have the opportunity to talk to Robin herself, his response was, “I hope you have a lot of time, because my mom loves to talk about dolls!”

The next generation

“I never thought my house would be full of dolls again.”

Today, a dresser in Holland’s small cyan sewing room is filled with an assortment of unclothed dolls in various conditions. Some she has purchased herself, while others have been sent to her by those eager to receive the Robin Holland treatment.

She and Arms are now friends, and their connection has allowed the former doll artisan to connect with some of her most ardent supporters. United across states and time zones, their passion is very much alive and greatly exceeds their size.

She does things a little differently this time. The love is still there, but now she creates at her own pace, no longer burdened by piling orders or the threat of accumulating debt. She enjoys traveling to various thrift and antique stores across the West for unique materials and items to dress her dolls, making only as many as she can or simply feels like.

All the same, her fans are just thrilled the master is back.

“I’ve met new people and friends through these dolls that I said goodbye to 30 years ago,” Holland said. “And suddenly, they’re coming back to visit me. You would never expect that because they’re inanimate objects.”

She doesn’t let it consume her life as it once did. When she’s not constructing a new Starshine she spends much of her time painting, which is a pastime that has proven useful in filling the walls of her colorful Tortosa home. Still, as she’s recently learned, there’s apparently something quite special that happens when she channels her creativity toward crafting miniature representations of America.

“Maybe there’s something more to it than I thought.”

This story was first published in the January edition of InMaricopa magazine.

![MHS G.O.A.T. a ‘rookie sleeper’ in NFL draft Arizona Wildcats wide receiver Jacob Cowing speaks to the press after a practice Aug. 11, 2023. [Bryan Mordt]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/cowing-overlay-3-218x150.png)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)