There is no voice like the voice of experience. Someone who has been there and done that is a more respected source than someone who has studied theories.

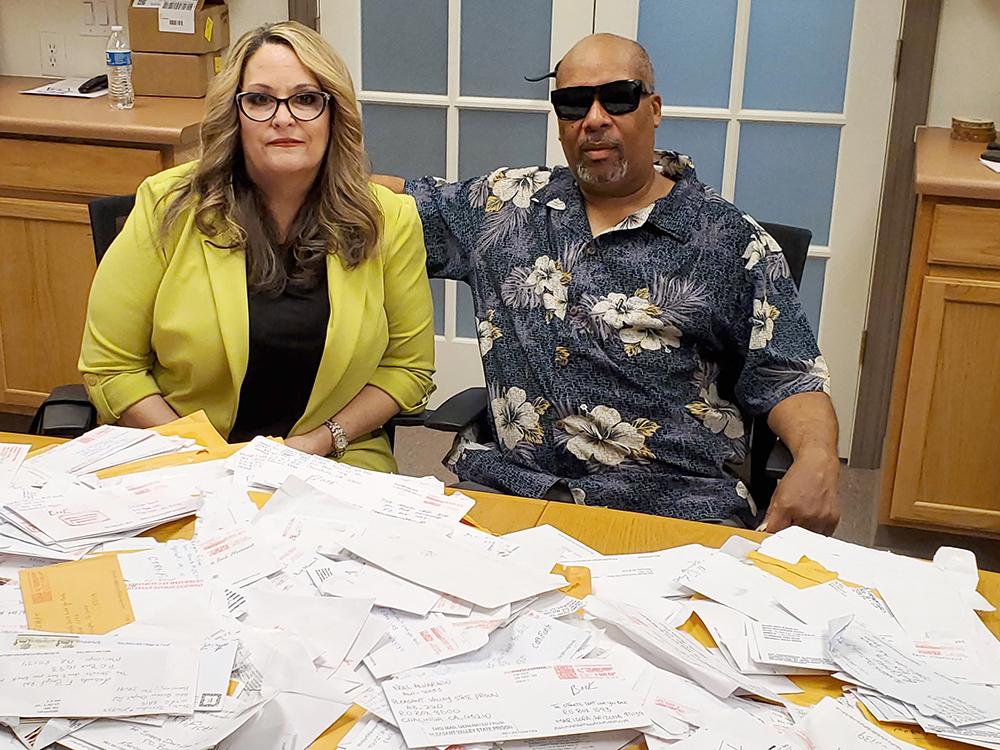

That is what makes Lucinda and Rob Boyd’s program, The Streets Don’t Love You Back, so effective.

The nonprofit organization co-founded in 2009 by the Maricopa residents is dedicated to equipping at-risk and incarcerated youths with tools to improve their situations through a variety of educational and life-skills programs. The program educates participants about the dangers of gangs, drugs, violence, abuse and other life issues, focusing on both prevention and intervention.

Rob and Lucinda, both 58, have lived the street life and come out the other side. The Villages residents know what put them on the streets – and also how to get off them.

“When you can get somebody who is incarcerated and let them learn from the life lessons of someone who has been there, that is an incredibly effective message,” said former Arizona state Sen. Steve Smith, who was instrumental in helping get the Streets program into Arizona’s jails and prisons. “For people who may be on the wrong path, they can hear from someone who’s walked in their shoes that there’s another way. That’s how you get people to pay attention.”

Rob’s experience with street and gang life was both firsthand and in-depth. He grew up in a ghetto on the east side of Detroit where his father, a prominent minister and well-known author, chose not to be a part of his life. His stepfather raised Rob and his siblings as his own, but when Rob was 9 he witnessed his grandfather stab his stepfather to death, a moment that changed the direction of his life.

By age 10, he was involved in a gang, dealing drugs and leading a violent street life – a life he lived for the next 35 years.

He eventually became the leader of the gang and a drug kingpin. After spending his youth on the streets, several years in prison, and all of his adult life as a gang leader, Rob began to realize the path he was on would lead to a short and unhappy life.

Lucinda had her own experiences in the streets. While never living the gang life Rob did, she had her own formative experiences, including being sexually abused and turning to alcohol as a teenager.

With time and wisdom, things changed.

“What got me out was when I met Lucinda,” Rob said. “I was 45 when I got out of the gang life, and she’s the one that got me out. I mean, I joined a gang at 10 years old and I had prayed to get out of that life for years, and for God to send me a good woman. When I met her, I realized that God had sent me someone I would listen to and who believed in me from Day One.”

Their connection was instant, but Rob faced a choice when they met. He was in the gang life, and Lucinda wanted no part of that.

“She knew I was in that life, and she gave me an ultimatum,” Rob said. “Now understand, in my position I was used to being the one who gave the ultimatums. But she told me it was either her or I could keep doing what I was doing. And God had something way bigger for me to do, so I walked away and closed the door on that life.”

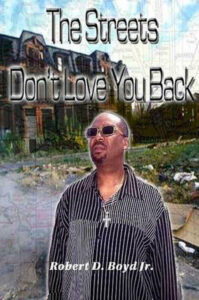

BASED ON THE BOOK

A new door opened for them almost immediately as Rob and Lucinda began working to develop The Streets Don’t Love You Back organization, based on Rob’s book of the same name. They put their experiences to work.

Once they had the program developed, they worked in the community and through Rob’s radio show to share their insights to help as many people as they could. Wanting a better program that could make more of an impact, Lucinda sat down and devised a curriculum and workbook on life skills and intervention.

“My goal was to reach out to youth and at-risk youth so they wouldn’t end up incarcerated or in the system and to help them before they got to that point,” Lucinda said.

Their first major rollout was with those who would need more than prevention. Inmates in Arizona’s jails and prisons were prime candidates.

A Detroit native, Smith heard about Streets and helped the Boyds get it into the prison system.

“I heard his story and saw what he’s doing with his life, and when you see people like that and how they give back and are so selfless and giving, how can you not want to help them?” Smith said. “He wanted to make it bigger and bigger, and we did whatever we could to help.”

Lucinda and Rob also gained the endorsement of the law enforcement community, which quickly saw the impact the program was having on those already on the wrong path and serving time.

The six-week, self-guided Life Skills Intervention Program includes education and discussions on substance abuse dependency, making decisions, anger management, attitude, behaviors, problem-solving, self-improvement, setting goals and identifying strengths and skills.

According to David Linderholm, detention officer in charge for the Pinal County Sheriff’s Office, the program is making a direct impact on the lives of inmates.

“Our inmates are extremely happy to have something like this as a way to learn and grow,” he said. “It’s vindication that they are taking steps to become a better person.”

One youth who gained from Streets is Dominic “Nico” Ciccirello. After being arrested for crimes including curfew violations and car theft, he was placed in the custody of Child Protective Services.

“Rob was always there for me,” said Ciccirello, now 18 and a licensed barber with a shop in Phoenix. “I’ve been involved with Streets since I was 13 years old. “He deals with very troubled kids, and I was one of them.”

FROM STREETS TO SCHOOLS

The next step for Streets is to expand its presence in school systems.

Maricopa Unified School District volunteer Jim Irving said he hopes to soon expand the program from Maricopa High School to two elementary schools, with a different twist to make it appropriate for fourth and fifth graders.

Irving said one of the reasons for the success of the program is Rob gets the kids talking about themselves rather than listening to him. He learns about their issues, then relates their experiences to what he’s been through and the bad decisions he’s made in his life.

Mayor Christian Price said part of the effectiveness of Streets is the program empowers people to make their own changes.

“What we don’t do enough in corrections, and what his program does do, is help kids actually problem-solve and make positive decisions,” Price said. “Plus, they’re spending an inordinate amount of their time and personal treasure to help others, and really, what more can you ask of someone?”

It doesn’t matter how great the curriculum is, or where it is available, if those in it don’t believe. And that buy-in is built through the obvious fact both Rob and Lucinda have walked similar paths and care deeply about helping those at risk or already incarcerated.

Rob said getting results is the bottom line.

“We define success by whether a person is doing the same things they were doing before they came into the program. If you were doing negativity and now, you’re doing positivity, that’s a success for us.”

HOW THEY MET

Rob and Lucinda Boyd didn’t meet on the street. They found love on the internet.

In 2009, Rob was writing songs and posting them on Myspace, one of the first social networking sites. Lucinda, a critical care nurse who has lived in Maricopa 37 years, happened to listen to one of Rob’s songs, and the rest was history.

“He was sharing a song that he had done and saw my picture and reached out to me because he thought I was cute,” Lucinda said. “We became friends first, and I got to know about him and his life living in the streets, and we talked a little about my life and my struggles. I knew that with my testimony and his testimony that we could reach out and help kids, and maybe they could talk to somebody, and they wouldn’t go through some of the same things that we went through.”

This story appears in the August issue of InMaricopa magazine.

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)

![Locals find zen with Earth Day drum circle Lizz Fiedorczyk instructs a drum circle at Maricopa Community Center April 22, 2024. [Brian Petersheim Jr.]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/PJ_3922-Enhanced-NR-218x150.jpg)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-100x70.jpg)

![Locals find zen with Earth Day drum circle Lizz Fiedorczyk instructs a drum circle at Maricopa Community Center April 22, 2024. [Brian Petersheim Jr.]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/PJ_3922-Enhanced-NR-100x70.jpg)