EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the latest installment in a series dealing with the Oatman massacre and the experiences of the family members who survived it.

You will recall that the family of Royce Oatman left Maricopa Wells in early 1851 and four days later were attacked by a group of 19 natives, whose tribe remains unknown.

Fourteen-year-old Olive and her seven-year-old sister Mary Ann watched in horror as their five siblings, their pregnant mother and their father were butchered. Lorenzo, their 15-year-old brother was clubbed on the head and thrown off a 20-foot embankment.

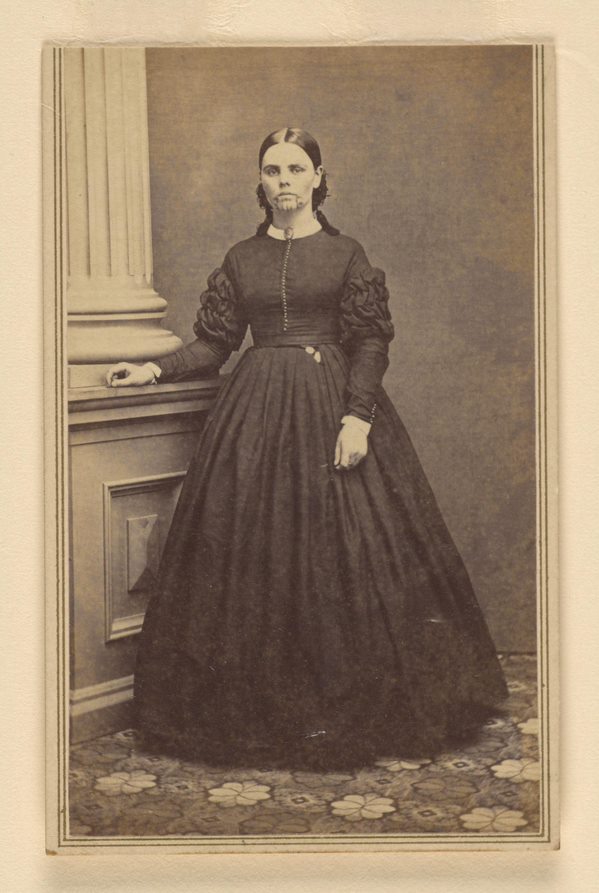

Olive and Mary Ann were forced to walk barefoot for days to the village of their captors where they endured a year of hard labor and abuse, before finally being sold to the chief of the Mojave tribe and his wife. Life with the Mojave tribe was peaceful and the Oatman girls were treated well. The chief and his wife adopted them into their family and treated them as their own daughters. But there came a season of drought, and the ensuing famine took the lives of many members of the tribe, including Mary Ann. Olive barely survived. Five years after the massacre, the commander at Fort Yuma learned that Olive was alive and living among the Mojaves and he sent an emissary to negotiate her release. Her adoptive father resisted at first, but when the negotiator made threats of reprisals against the Mojaves by the soldiers at Fort Yuma, he was forced to capitulate.

We will continue the story from the personal perspective of Olive Oatman.

You are Olive Oatman. It has now been five years since the massacre of your family. After all you have endured during those years, once again your future is being decided by others.

You are being returned to White society.

Aespano, the wife of the Mojave chief, the woman who has adopted you and loved you like a daughter, is disconsolate at your departure. The historical record does not make it clear if you want to go back to the world of your fellow whites, or if you prefer to stay with the people who have treated you so well for the past four years and whose language and ways have become your own, but one can imagine that you are filled with mixed emotions.

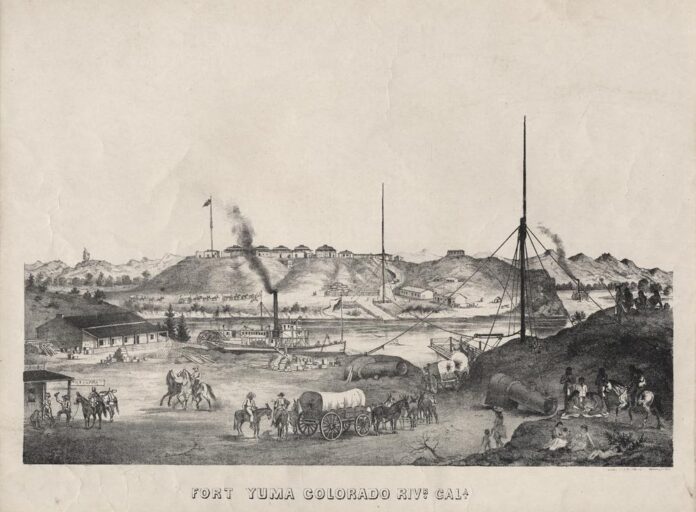

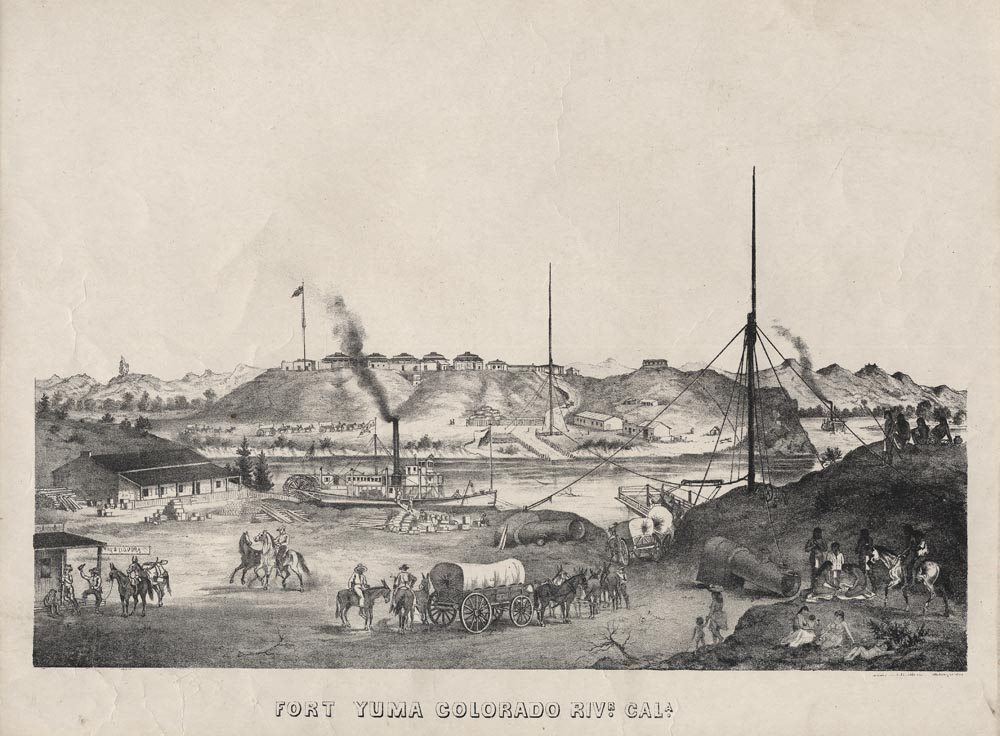

On Jan. 22, 1856, after an arduous 10-day journey by foot, you and the Mojaves accompanying you reach Fort Yuma. At this point in your life, you look every inch a Mojave woman.

A calico dress is brought to you as you arrive at the fort. You are taken to see the camp commander, who attempts to interview you, but you have nearly forgotten the English language and you struggle to answer basic questions.

However, you still understand spoken English and the camp commander tells you something you had not imagined to be possible, the shock of which is so great it causes you to faint: Your brother, Lorenzo, is alive. And he has been searching for you.

We will return to the day of the massacre:

You are 15-year-old Lorenzo Oatman. Your family is being slaughtered by hostile natives.

You have been clubbed on the head and are bleeding profusely. You regain partial consciousness and struggle to rise. The natives see this, and they carry you to the edge of a 20-foot embankment, hurling you over the precipice, confident that the jagged rocks below will finish their murderous job.

Hours later, you regain consciousness and drag yourself back up the embankment, where you find the bodies of your family members strewn about the site like so many rag dolls.

Your feelings at that moment can only be imagined. The horror you feel is worsened by the fact that the bodies of two of your sisters, Olive and Mary Ann, are missing from the scene and you realize they have been taken by the hostiles. Taken for what? you ask yourself, and you imagine scenarios more horrible than the fate that overtook those who lie dead on the ground around you.

The natives have taken everything of value from the wagon. You have no food or water. You begin walking. You struggle to remain upright, falling often, frequently losing consciousness. You hallucinate, seeing fantastic forms and scenes. You are beset by wolves. They follow you; they lick up the blood that drips to the ground from your wounds.

Some of them come right up to you, apparently sensing you are too weak to be a threat to them.

Nightmarish days and nights pass. Finally, you encounter two Pimas who give you a little food and water and tell you they will return. Shortly after they leave, you see some wagons in the distance. You approach them and gratefully find that these travelers are friends from your old wagon company. You, and some of the men, return to the scene of the massacre to bury the remains of your family. When you get there, you find bones and body parts scattered around the site. Scavengers have been eating the bodies of your beloved parents and siblings.

A month after the massacre you finally are sufficiently recovered from your injuries to return to Fort Yuma. You vow you will never stop searching for your two sisters.

To be continued in the January 2022 issue of InMaricopa

C.M. Curtis, American Western author and historian, is the best-selling author of 11 books, including eight westerns. His books can be found on Amazon or at www.cmcurtisauthor.com

This story was first published in the December edition of InMaricopa magazine.

![Maricopa’s ‘TikTok Rizz Party,’ explained One of several flyers for a "TikTok rizz party" is taped to a door in the Maricopa Business Center along Honeycutt Road on April 23, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-042324-tiktok-rizz-party-flyer-web-218x150.jpg)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)