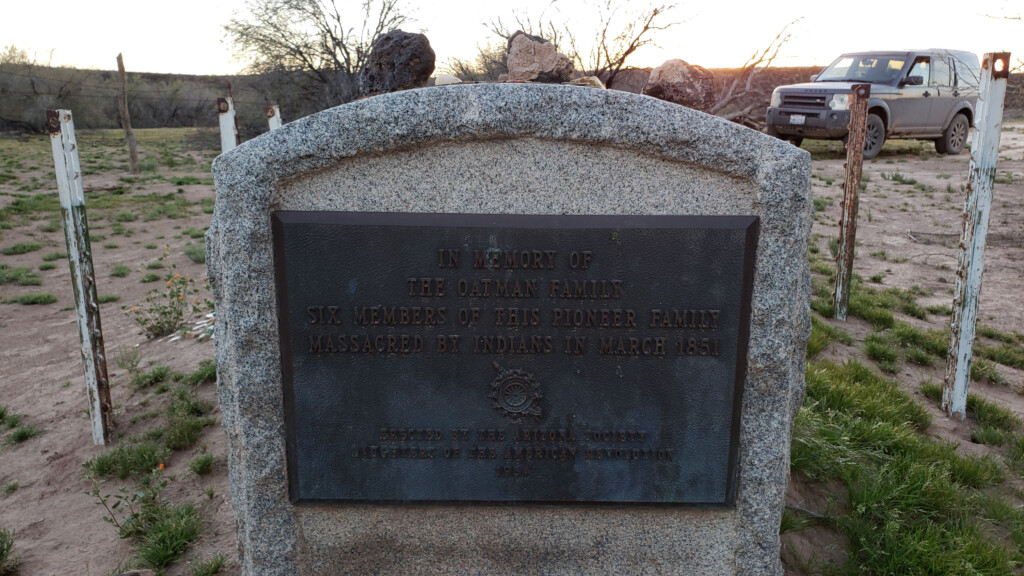

The massacre of the Oatman family in 1851 sent a shock wave through the Arizona Territory.

Undoubtedly, the residents of Maricopa Wells (ancestor of the current city of Maricopa) were particularly affected, in view of the fact the Oatmans had recently stayed there and left just a few days earlier.

The family had left Independence, Missouri in August 1850 as part of a large wagon company en route to California. In early 1851, traveling with a group of about 30 wagons that had split from the main company, they stopped in Maricopa Wells, which was populated primarily by Pima and Maricopa natives. There was word of some trouble with natives on the trail between there and California, so the other travelers decided to wait until it became safer to travel. But Royce Oatman decided to take the risk, and he and his family continued on alone.

It was a very bad decision.

You may know by now I believe history is best experienced through the personal perspective, so we will put ourselves in the places of Olive Oatman and little Mary Ann Oatman, two of Royce and Mary Ann Oatman’s seven children.

OLIVE OATMAN

You are 13 years old. Four days out of Maricopa Wells, you and your family are traveling alone in one of the most desolate and hostile parts of the southwestern desert — indeed, of the world — when your 15-year-old brother, Lorenzo, sees a group of 19 natives approaching. They act friendly and ask for food. Your father gives them some; they eat it and demand more. Your father refuses, saying there is not enough for his family.

The natives go a short distance away and have a brief discussion, after which, with deafening war cries, they attack your family with clubs. They kill your parents and four of your siblings, including a baby boy and a 3-year-old girl. You are also clubbed in the head and unconscious for a short time. You awake to a horrific scene. Your 7-year-old sister, Mary Ann, is at your side. She cries, “Oh Mother, Oh Mother! Olive, Mother and Father are killed, with all our poor brothers and sisters.”

Your oldest sibling, Lucy, lies dead, cradling the body of your baby brother. Your mother groans. You spring toward her but are held back by one of the attackers.

Your brother, Lorenzo has been clubbed. You see he is bleeding copiously from his nose and ears. He stirs and tries to get up, but the attackers pick him up and hurl him over the edge of the mesa, roughly a 20-foot drop.

You and Mary Ann are forced to watch as the natives strip the bodies of your loved ones and ransack the wagon. They take your bonnets and shoes and force you to walk barefoot to their camp, miles away. Your feet are worn raw by the rocky, volcanic terrain, but if you falter you are beaten.

At their camp, the men laugh and mock as the two of you sit sobbing. They offer you food but you are unable to eat; your grief and fear are too great. The next day you begin a four-day march across the desert.

MARY ANN OATMAN

You are 7 years old. Your world has just been turned upside down. You have seen things no one should ever have to witness, much less someone your age.

Now you are being forced to walk barefoot on the rocky desert floor, expected to keep up with the fast-walking men. You fall frequently and are beaten with a whip until you get up. When you lag behind, you get the whip. Olive helps you as much as she can, but she too is struggling. You tell her you want to be allowed to die. Finally, you fall to the ground, unable to walk another step. One of the men picks you up and slings you over his shoulder like a sack of flour and carries you the rest of the way. In this manner, walking and being carried by one of the men who slaughtered your family, you travel about 90 miles to the village of your captors, where you and Olive are subjected to cold, hunger, overwork, ridicule and beatings, and treated as slaves.

It will never be known for certain to what tribe the men who killed your family belonged.

OLIVE OATMAN

Life in the village of your enemies is a nightmare for you and Mary Ann. Later, referring to that time, Royal B. Stratton, who will write a controversial book about your experiences, will pen, “Much of that dreadful period is unwritten and will remain unwritten forever.”

One can only imagine the horrors you both suffer. This village is in the mountains and it is winter. Your clothes have fallen apart, and you have no protection from the cold. You weave some coverings out of plants, which do little to keep you warm. Mary Ann becomes malnourished and weak. You both pray constantly to be rescued from this hell you are enduring. It takes great strength to merely survive from one day to the next. What must be your anguish when you see an article of clothing that was taken from the body of one of your loved ones being worn by one of your captors? Do you dare hope for rescue? You wonder if anyone even knows about the massacre. And if they do, how could they possibly know where to look for you? Everything seems bleak and hopeless.

But you force yourself to remain alive, for the sake of your little sister.

(To be continued in the November edition of InMaricopa magazine.)

C.M. Curtis, American Western author and historian, is the best-selling author of 11 books, including eight westerns. His books can be found on Amazon.com and atcmcurtisauthor.com.

This story was first published in the October edition of InMaricopa magazine.