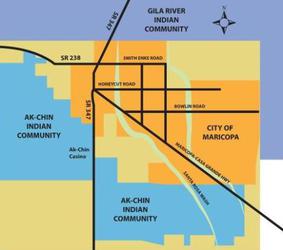

As city leaders continue to position Maricopa for success in the battle for new businesses and their accompanying jobs, they face diverse competition from two neighbors with large cash accounts and decades more experience: the Ak-Chin and Gila River Indian Communities.

The scenario is not unique to Maricopa, however. “Municipalities and states are not used to having to compete with tribal communities for economic development projects, but they are a real and viable player; and the sooner government entities realize it, the better,” said Joe Kalt, director of Harvard University’s project on American Indian Economic Development.

The concept of commercial development for the Gila River Indian Community, Maricopa’s neighbor to the north and east, began in the late 1960s, but projects didn’t materialize until much later.

“We had plans early on, but we were not able to start to act on them until we started gaming on the tribal lands and had some money available to start investing in development,” said the community’s treasurer, Arthur Felder.

Those monies helped add infra-structure early on to support development, but Greg Guedel, chairman of Native American Legal Services, said two of the real driving forces behind the movement to develop on tribal land were a desire to break dependence on the federal government and members of the tribes becoming more knowledgeable. Conventional wisdom suggests profits for the tribes and individual Indian landowners also played a large part.

American Indians living on the nation’s 300 reservations are among the poorest people in the United States, Guedel said. “Tribal leaders have realized if they are going to raise the standard of living in their communities, they have to take matters into their own hands.”

Other forces behind these winds of change, according to Guedel, included federal tax incentives to build on tribal land and the establishment of planning departments within tribal governments.

Harvard’s Kalt said, “In many ways tribal governments were like small cities that started with no services, but, as services started to materialize, they became players.”

Competitive differences

When economic development personnel from a municipality pitch their community to a developer, the focus is often on what it can offer that other municipalities cannot. It is no different on tribal land.

“Companies are always looking at the bottom line cost, and many can’t compete with the types of deals these tribal communities can offer,” said Lance Ross of Ross Property Advisors, a Scottsdale commercial real estate firm whose clients include the Ak-Chin Indian Community.

Indian communities are sovereign nations, so they can offer developers who build on their land substantial incentives, which can add up to hundreds of thousands of dollars per year, creating a huge competitive advantage.

Also not applicable are many of the public hearing requirements required in municipalities. “If tribes have the desire to get a project done, they can move much faster than cities and counties,” Guedel said. “The faster a development is completed, the sooner it can start making money.”

In addition to fewer taxes and less red tape, tribes can also provide financing, cash assistance and other perks to help lure business away from non-Indian land.

“We are very flexible when working with a business, and, if what they bring to the table matches what we are looking for, we will find a way to get the deal done,” said Lester Tsosie, Ak-Chin’s senior community planner.

While Indian communities can provide very large incentive packages to lure businesses to their lands, the federal government has also opened its wallet to provide tax credits, grants and other opportunities for companies locating on Indian land. One such example is a $20 million tax-exempt bond granted to build a $100 million spring training facility for the Arizona Diamondbacks and Colorado Rockies on the Salt River Pima-Maricopa reservation near Scottsdale.

While the tribal communities are able to offer financial packages and streamlined processes, they cannot convey ownership of their land. This may be a “deal killer” to businesses that don’t want to spend their money leasing and improving someone else’s asset. In addition, most Indian leases require the developer to turn over the build-ing and improvements it paid for to the tribe at the end of the lease.

Many Indian communities also have strict employment practices providing preferential treatment to Native Americans, which is a turnoff to many businesses operating in the free market.

“During most of the 20th century tribes have lost out on commercial developments to cities, but that is now changing,” Guedel, of North American Legal Services, said. “Tribes are now definitely competing with cities, and they are oftentimes doing it quite successfully.”

Nearby tribal developments

The major center for development on the Gila River reservation is off State Route 347 near Interstate 10; it includes Sheraton Wild Horse Pass Resort & Spa, Wild Horse Pass Casino & Hotel, Whirlwind Golf Club, Raw-hide, Koli Equestrian Center, Firebird Raceway, an office building and a gas station, all of which are owned by the Community.

“It is one area we have really concentrated on, and we are hoping to bring future retail to the center,” Felder said.

However, it is not the only area the Community plans to develop.

Gila River land surrounds I-10, SR 347 and perhaps the future Loop 202 corridor, and the Community plans to develop these lands, Felder said. Land the Community owns that abuts other cities such as Phoenix, Chandler, Tempe, Gilbert and Queen Creek is also poised for future development.

While the Gila River Indian Community is home to multiple casinos, hotels, golf courses and tourist attractions, the Ak-Chin Indian Community, which borders Maricopa to the south and west, is rapidly working to create its own real estate portfolio.

The Ak-Chin Indian Community purchased Phoenix Regional Airport, which is less than a mile east of the city limits along Maricopa-Casa Grande Highway in 2006. In the first seven months of 2010, the Community opened its wallet and purchased Southern Dunes Golf Club, a private golf club with 320 acres less than a mile west of the city on State Route 238, and broke ground on a hotel expansion at Harrah’s Ak-Chin Casino and an of-fice/warehouse flex building on Maricopa-Casa Grande Highway and Murphy Road.

The building, the first project planned for the 100-acre Santa Cruz Commerce Center, is a five-suite commercial plaza the Community intends to lease to light industrial and manufacturing businesses. According to Tsosie, the community is looking to lease the remaining acreage, which has water, sewer and power infrastructure in place, to green technology and industrial firms. Retail may be developed along the highway frontage as well.

The Community spent $2 million to get the land “shovel ready.”

Working together

Maricopa’s leaders are working to keep lines of communication open between the city and its neighboring Indian communities. “About five years ago we had very limited interaction with the city,” Tsosie said, “but we have formed a respectful partnership and communicate regularly.”

Maricopa City Council, which is not privy to either Ak-Chin’s or Gila River’s development plans, meets with the Ak-Chin Tribal Council once a year. “We want to establish a close bond with both tribal communities,” said Maricopa Councilman Marvin Brown, who is the city’s appointed liaison for that effort.

“While it would certainly be ideal for companies to locate in the city, we currently don’t have opportunities for light industrial,” said Danielle Casey, the city’s economic development director. “It is better to get jobs near Maricopa than to lose them to another city.”

Jim Rives, president and CEO of the newly formed Maricopa Economic Development Alliance, said he would like to see the relationship the city has with the neighboring Native American communities be similar to that of sister cities. “Any employees that their developments bring will shop at our stores,” he said. “I don’t know anything negative regarding tribal economic development.”

Both Tsosie and Felder said their communities’ visions are to work with their neighbors to create a viable future for all.

“The secret to success is when neighboring governments learn to cooperate,” Harvard’s Kalt said. That is key for Maricopa, which is virtually landlocked by Indian communities with abundant land, cash, tax benefits and water rights.

File photo

A version of this article appeared in the August issue of InMaricopa News.

![Elena Trails releases home renderings An image of one of 56 elevation renderings submitted to Maricopa's planning department for the Elena Trails subdivison. The developer plans to construct 14 different floor plans, with four elevation styles per plan. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/city-041724-elena-trails-rendering-218x150.jpg)

![Affordable apartments planned near ‘Restaurant Row’ A blue square highlights the area of the proposed affordable housing development and "Restaurant Row" sitting south of city hall and the Maricopa Police Department. Preliminary architectural drawings were not yet available. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/041724-affordable-housing-project-restaurant-row-218x150.jpg)

![Elena Trails releases home renderings An image of one of 56 elevation renderings submitted to Maricopa's planning department for the Elena Trails subdivison. The developer plans to construct 14 different floor plans, with four elevation styles per plan. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/city-041724-elena-trails-rendering-100x70.jpg)