Fred Greenspan’s advocacy for the Deaf community started 13 years ago while living in Mesa.

An early arrival for a business meeting at a diner in Phoenix, he asked a fellow customer four seats away to pass the milk and sugar for his coffee while he waited.

Repeated attempts garnered no response.

“I thought people in Arizona were supposed to be friendly,” Greenspan wondered.

He eventually learned, by a conversation written on a napkin with the fellow diner, that the man was a deaf college graduate with good grades and a degree in computer science who came to the diner every day with his computer to search for jobs.

Greenspan got to know the young man and found his six-month employment quest had resulted in frustration and getting “ushered out the door quickly” when he did get an interview.

Looking to help, Greenspan called a friend, who was CEO of a credit union, where the deaf man would go on to work for several years. The CEO told Greenspan, “Fred, you should teach this,” referring to his ability to open the lines of communications between the two parties.

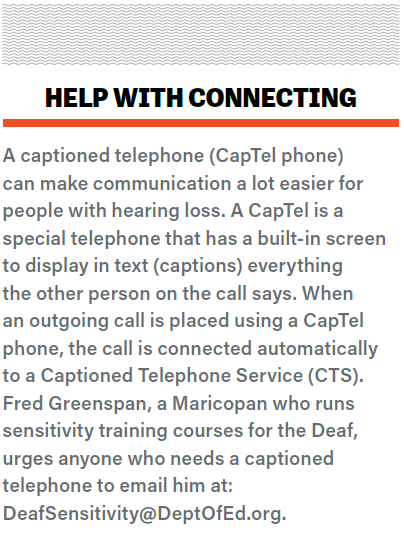

Greenspan, who is also hard of hearing, took it as a sign and enrolled in classes at Mesa Community College and later created a deaf-sensitivity training class titled “I Never Gave THAT A Thought!”

But Greenspan and other Maricopans have given thought to the challenges faced by the Deaf community in Maricopa, including finding opportunities and available services.

It’s a double-edged sword. The stigma attached to being deaf or hard of hearing can sometimes lead people with the condition to remain silent. As a result, it’s difficult to quantify the size of the community in the city, making outreach and delivery of services difficult.

In 2015, Greenspan organized “Here Us, Hear Us” social gatherings in Maricopa, as a way for the Deaf and hearing communities to come together. Later, pre-COVID, Starbucks’ locations in Maricopa and Casa Grande were sites for get-togethers for deaf residents.

Greenspan isn’t alone in his efforts of outreach.

Kasey Turik, a teacher at Heritage Academy, was pleasantly surprised when she offered an American Sign Language course at Heritage last year.

More than 180 Heritage students registered for the 50 spots in the two ASL 1 classes, Turik said.

“This is something that is out there and let’s see how our community can get involved,” she said of her motivation. “We want to make it more welcoming for the Deaf community. I want them to know our students are learning how to communicate with them. I just want to open up the communication channels.”

Those completing the first class a year ago are now in ASL 2, with two new ASL 1 sections being offered. Again, demand surpassed the available seats.

One man’s story

Greenspan used sign language and texting to chat with a 39-year-old deaf man (who asked not to be identified) who has spent much of his time in Maricopa over the past decade.

The man said he has alternated living between Maricopa and an out-of-state location since 2011. He currently does not have a job in Maricopa.

“There’s not too much to pick from,” he signed, of employment opportunities for the Deaf. “That’s why I go back and forth, back and forth.”

Greenspan said the man had previous jobs at a local restaurant and retail stores. While managers were on board, staff either did not know he was deaf or were unable to make accommodation.

“They treated him like a little baby, which defeats one’s self-worth,” Greenspan said. “Sometimes when you have a door opened, it might be an open door with a brick wall right behind it.”

The challenges are “often problems with communications,” the man said, citing as examples the difficulty of reading lips or the employer/business not having an interpreter in place to assist.

Asked whether improvements have been made over the last decade in society’s efforts to effectively communicate with the Deaf, Greenspan quickly replied.

“It’s gotten worse,” he said. “Ignorance plays a giant part in it.”

Learning to succeed

One of Turik’s ASL 1 students this year is 15-year-old sophomore Miranda Schroeder. At age 3, she failed a preschool hearing test and was eventually found to be totally deaf in her left ear. Her twin brother has no hearing issues.

“I did sign language with them when they were babies before they started speaking,” said Miranda’s mom, Carrie Schroeder, who had no idea hearing challenges would impact her family. Miranda, however, finds ways to adjust and is adamant she will not be prevented from reaching any of her goals in life.

Since fourth grade, she has taken advantage of a frequency modulation system. Miranda’s teachers wear a small microphone, with the sound delivered directly into the receiver in her hearing aid. At times, she will use the system in choir practice — giving one of her classmates the microphone so Miranda can hear the proper notes and pitch.

“When people are talking, I tend to turn my ear toward them,” she said. “Or, if we are in the hallway at school and someone is on my left side, I will go to the other side of them.”

She also utilizes captions as much as possible, although there are serious limitations.

Some movie theaters, for example, make assistive listening devices available and others do not. Even when in use, “sometimes the captions come up on the screen too soon or too late,” Miranda said. “On YouTube, when the captions are automated, they tend not to work. Sometimes they say the most ridiculous things.”

Both mom and daughter are thankful Miranda still has some hearing.

Miranda admits there are still times people don’t understand why she is using captions or turning up the volume to hear better.

“If they don’t understand, I prefer they ask,” the teenager said. “I guarantee I won’t be offended. I just really want to learn as much as I can. I know I’m lucky to have hearing in my right ear. I just want to help people who are deaf.”

While many her age are still pondering the future, Miranda has shifted from an initial goal of becoming a teacher to instead focusing on a legal career in child advocacy. She is currently taking an elective in criminal law that earns both high school and college credit.

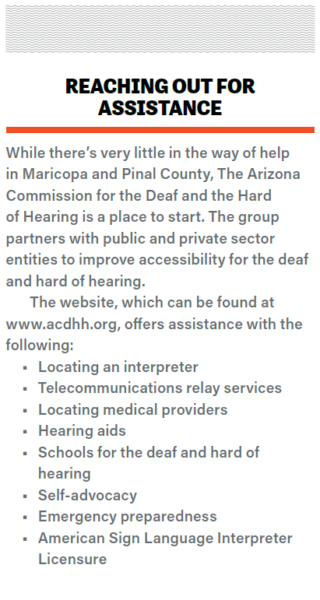

Limited outreach

Limited outreach

A new videophone service was unveiled at the Maricopa Public Library in 2018. It incorporates interpreters, allowing the Deaf and Hard of Hearing to communicate with those who don’t know sign language.

City officials cited the videophone — which originated from a grant — as one public service offered, but staff at the Maricopa Library & Cultural Center say they are not aware of much usage.

It’s difficult to get a count of the city’s Deaf population and there are few indications deaf residents have many local employment options or significant programs to help them thrive.

Inquiries to major employers in Maricopa revealed no official count of deaf employees. All were asked about their own workforce and how they serve deaf customers, patients or students.

Representatives of Maricopa, Walmart and LaQuinta Inn & Suites confirmed they have no deaf employees. A public relations representative for Harrah’s Ak-Chin noted “hearing impaired rooms” are available at the hotel with flashing lights and other visual signals in case of emergencies.

AnnaMarie Knorr, the community outreach coordinator for Exceptional Community Hospital-Maricopa, responded via email that “we have programs and services available to assist the Deaf and Hearing Impaired, should they need medical care, and we are and always have been an equal opportunity employer.”

Lindsay Stollar Slover, Director of Exceptional Student Services for Maricopa Unified School District, said the system’s goal is to approach each situation on individual basis.

“We always prioritize the needs of the individual student,” she said, declining to give the total number of students who are deaf or hard to hearing, citing privacy concerns. “We get to know the student and their wishes and goals, and make sure we understand what those needs are.”

The district has an ongoing partnership with the Arizona State School for the Deaf and Blind. The agreement provides classroom services for students and “assessment and support as well as training for teachers.”

The district has an ongoing partnership with the Arizona State School for the Deaf and Blind. The agreement provides classroom services for students and “assessment and support as well as training for teachers.”

Rather than broad district-wide instruction for all teachers, Stollar Slover said the unique needs of deaf students make it better to “bring teachers in to provide some specific training for that student.”

She recalled while serving as a principal in another district a deaf student in her school desired no special help and wanted to be treated like all other students.

Teaching moments

Reducing the ignorance or lack of knowledge, at least among some high school students, is among Turik’s goals. She is in her second year of teaching ASL, with students able to take two years of classes to fulfill their world language requirements. The plan is for a third-year class in 2023-2024 to be dual enrollment, providing both high school and college credit.

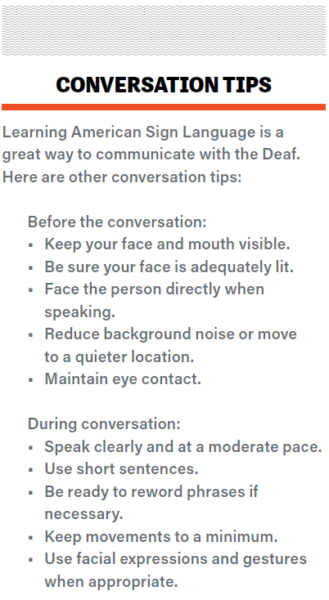

“In level one, we do vocabulary as much as possible and some grammatical structure,” she said. “It is not the same word order between English and ASL. On the cultural side, we study how to get a deaf person’s attention, and I want them to be comfortable doing an introduction.”

The ASL 2 classes this year are expanding the vocabulary and cultural work. They also incorporate additional activities that, while unable to duplicate the challenges facing the deaf, give the students an idea of what it is like.

Turik’s daughter, Emily was in one of the first ASL classes last year. This summer she used sign language in her job to communicate with a deaf family that came to the local yogurt shop. “She was so excited, particularly about how happy they were that someone could communicate with them,” Turik said.

A longtime teacher in both Texas and Arizona, Turik is pleased to finally capitalize on her interest in ASL. She took classes at both Pima Community College and online at Rio Salado College after first learning some sign language as a third grader in Washington state.

Doing it all

Greenspan has seen the proverbial light bulb go on for many who have taken part in his sensitivity-training sessions. The first takeaway he likes to see is “they learn the ASL alphabet. It’s easy.” A phrase he emphasizes is, “When in doubt, write it out … but be sure the deaf person knows English.”

The bottom line is similar for all.

Advocates say the Deaf and Hard of Hearing community is a linguistic and cultural minority with lives full of beautiful and rich traditions.

Still, many students are surprised by what they learn when watching videos about the Deaf community, Turik said.

“It also makes them realize that being deaf is not your entire world,” she said. “There are things you might have to do a little differently, but you can still do every single thing that any hearing person can do … but hear.”

Carrie Schroeder said her daughter’s deafness in one ear “has not stopped (Miranda) from doing anything she wanted to do.”

Her condition will never hold her back, Miranda acknowledged.

“I may sometimes need to ask more questions or need slightly more help, but I can still do it.”

This sponsored content was first published in the Health Guide, which first published alongside the October edition of InMaricopa magazine.

![Elena Trails releases home renderings An image of one of 56 elevation renderings submitted to Maricopa's planning department for the Elena Trails subdivison. The developer plans to construct 14 different floor plans, with four elevation styles per plan. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/city-041724-elena-trails-rendering-218x150.jpg)

![Affordable apartments planned near ‘Restaurant Row’ A blue square highlights the area of the proposed affordable housing development and "Restaurant Row" sitting south of city hall and the Maricopa Police Department. Preliminary architectural drawings were not yet available. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/041724-affordable-housing-project-restaurant-row-218x150.jpg)

![Elena Trails releases home renderings An image of one of 56 elevation renderings submitted to Maricopa's planning department for the Elena Trails subdivison. The developer plans to construct 14 different floor plans, with four elevation styles per plan. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/city-041724-elena-trails-rendering-100x70.jpg)

Is there a class in Maricopa for people who want to learn ASL? I, for one, would love to learn.

Check with Central Arizona College or any of the Maricopa Community College campuses for ASL classes.