Like most Maricopa residents, I have driven past Pima Butte (“M” mountain) many, many times. But only recently did I learn that a significant event in American history occurred on and around that landmark.

I believe the best way to study human history is to put ourselves in it. After all, though we may think those people back then were different from us, they weren’t. True, their lifestyle was different, and they had different customs, but all human beings are essentially the same. There is no reason why we can’t relate to what they felt and how they were affected by events in their lives.

So, let us begin. Let us experience vicariously the famous Battle of Pima Butte.

As with many historical events, there’s a good deal of backstory about the event we don’t know. One thing we know is the two tribes — the Yumas and the Maricopas — had a long history of mutual hostility.

Sources disagree on the date of the event. Some say it occurred June 1, 1857, while others put it on Sept. 1 of the same year. My thinking is it happened in June because mesquite beans were being gathered. These ripen in early June and need to be harvested before the July monsoon storms. Either way, June or September, it was summer in the Arizona desert. Enough said.

The man who planned the attack chose his season poorly.

His name was Francisco. He had recently been made chief over the Yumas and — it is believed — was eager to prove himself to be a great war chief. He assembled a battalion of about 300 Yumas, Apaches, Yavapais and Mojaves and in eight days these allies walked nearly 200 miles, arriving at Maricopa Wells weary and hungry.

Things were about to get worse.

As is generally the case in human events there are different, and sometimes conflicting, versions of what happened over the next two days, but on some points most accounts agree. I will stick to those points.

The first act of war of the invaders was to kill a group of Maricopa women who were away from their village gathering mesquite beans. The women and children who had remained in the village heard the Yumas coming and fled to viva’vis, the mountain we now call Pima Butte. They climbed to the top, hoping they would be safe there.

The Yumas spared one of the mesquite bean gatherers to use her as a guide. Her brother was a well-known warrior, and she was forced to lead them to his dwelling, whereupon she was immediately killed.

Her brother fled. The invaders chased him, but he was fleet of foot and they were still weary. They shouted at him to stop and die like a man, but he was no fool. He told them if they were able to overtake him, he would show them how to die like a man.

The Yumas burned the village. Then, Chief Francisco made another blunder. He and his men remained in the village, resting and eating the food they found there. No doubt they needed both the rest and the nourishment, but a good general must think beyond such things and assess the larger picture.

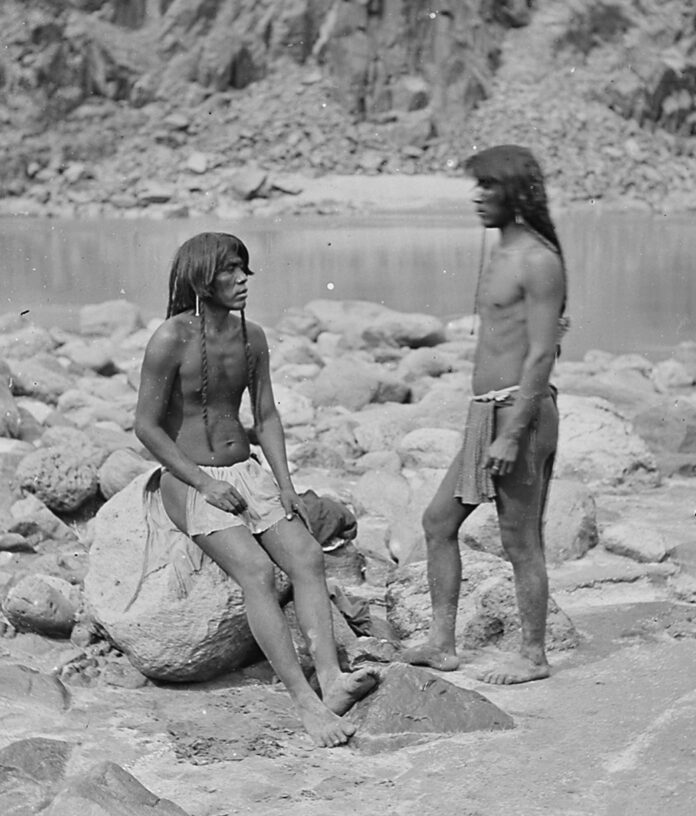

North America, took its name because it occurred near the mountain most Maricopans know

as “M” mountain. Photo by Brian Petersheim Jr.

Before proceeding, allow me to state that I am not taking sides. True, the Yumas were the invaders in this case, but it is claimed this raid was done in retaliation for a raid the Maricopas had previously made on the Yumas. I suspect those raids had been going on back and forth for longer than anyone in either tribe even remembered, irrationally perpetuating ancient and deeply entrenched hatreds.

Kind of like the rest of the human race.

Here’s where we insert ourselves into the story. Let’s step into the moccasins of the Maricopas. It goes without saying we are plenty honked off. We are determined not to allow these enemies to go unpunished. For the rest of that day and throughout the night we send messengers to all the Maricopa villages roundabout as well as to those of our allies, the Pimas, gathering men to fight the invaders.

Now, let’s put ourselves in the moccasins of certain members of the attacking host; specifically, the Apaches, the Yavapais and the Mojaves who are accompanying the Yumas, but whose fight this is not really.

Let’s face it, we are not having fun yet. There was all that walking, and the hunger, and now we are just hanging around this village, giving the Maricopas plenty of time to assemble a body of warriors large enough to wipe us out. This Chief Francisco is not all he was cracked up to be.

So, we leave. Problem solved — at least for us.

Now, all that remain are the Yumas and a few Mojaves. By morning they are surrounded by a host of very angry Maricopas and Pimas, whose strategy is to keep them from breaking through to the river — oh yes, and to kill them all.

Think of the pitiable state of the Yumas — still weary from their long march, still in need of food, surrounded and outnumbered and desperately thirsty as the fight rages all through the blazing summer day.

The battle took place on a flat area somewhere south of Pima Butte and, except for one wounded warrior who was thought to be dead, but who, when night came, slipped away in the blessed darkness, all the Yumas — including Chief Francisco — were slaughtered.

Their bodies — an estimated 160 of them — were never buried, just left where they had fallen.

It was the last great battle fought on North American soil between native tribes.

C.M. Curtis, American Western author and historian, is the best-selling author of 11 books, including eight westerns. His books can be found on Amazon.com and atcmcurtisauthor.com.

This story was first published in the September edition of InMaricopa magazine.

![MHS G.O.A.T. a ‘rookie sleeper’ in NFL draft Arizona Wildcats wide receiver Jacob Cowing speaks to the press after a practice Aug. 11, 2023. [Bryan Mordt]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/cowing-overlay-3-218x150.png)

![Maricopa’s ‘TikTok Rizz Party,’ explained One of several flyers for a "TikTok rizz party" is taped to a door in the Maricopa Business Center along Honeycutt Road on April 23, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-042324-tiktok-rizz-party-flyer-web-218x150.jpg)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)

![MHS G.O.A.T. a ‘rookie sleeper’ in NFL draft Arizona Wildcats wide receiver Jacob Cowing speaks to the press after a practice Aug. 11, 2023. [Bryan Mordt]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/cowing-overlay-3-100x70.png)