By Michael K. Rich

John Smith, a Maricopa resident since 1951, sits in an old reclining chair by his living room window, looking out at the sea of rooftops that were once farms. He describes an event that helped transform Maricopa.

“Mike Ingram used to sneak out every night and hang that sign.”

The sign he refers to transforms state Route 347 into John Wayne Parkway as it runs through town, and many were opposed to that change, according to Smith. “The Indian communities didn’t want the change because John Wayne was known for killing Indians, and the old timers just wanted it to remain Maricopa Road.”

Ingram, the developer behind much of modern-day Maricopa, insists the county was putting up the signs, and people taking them down were trying to have Duke memorabilia to hang on their walls.

Although he was able to get the sign approved, Ingram said he could understand the feelings of the early residents who didn’t want to change the road’s name. Although some of the Indian communities had issues with Wayne, the Ak-Chin did not, according to Ingram. “They worked and drank with the man.”

“I changed the name to honor a great man who made an incredible contribution to western Pinal County,” Ingram explained. “He (Ingram) loved John Wayne and thought it would be a great marketing ploy,” Smith said.

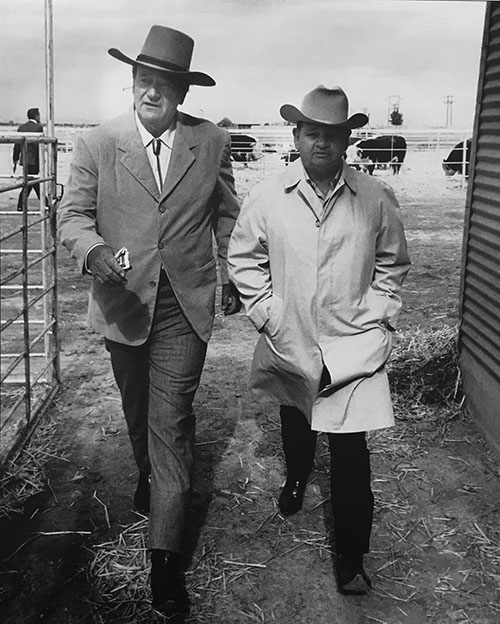

However, Wayne, a.k.a. The Duke, is more than just a marketing tool for the city. He has a history with the area that stretches back to the late ’50s when the Hollywood legend purchased 4,000 acres of farmland between Maricopa and Stanfield. He paid $4 million in borrowed money for the acreage because his tax attorney thought it would be a good investment.

Cotton farmer

Wayne financed a cotton crop through Anderson Clayton Company of Phoenix, one of the largest cotton brokers in the world.

Then, due to a lack of time and farming experience, Wayne paid the brokerage to farm the land for him.

It soon became clear to Wayne that the Anderson Clayton Company didn’t know how to farm cotton either.

During Wayne’s many visits to his farm he noticed the farm of his neighbor, Louis Johnson, was doing considerably better than his own, according to Johnson’s widow, Alice.

“The Duke’s farm was struggling, so he called his brokerage people and asked who the best cotton farmer in the area was. They told him Louis Johnson,” Alice said. “When everyone else was getting two and a half bales to the acre, Louie was getting four.”

Convinced that Johnson was the farmer Wayne needed to make his floundering property a success, he called him. Explaining he couldn’t come to Arizona because he was making a film, he offered to cover all expenses if Johnson would fly to California to talk with him.

Johnson agreed to meet Wayne, and the outcome of their discussion was that Johnson would manage Wayne’s crop for one year for $14,000. If the farm produced three bales per acre, he would receive an additional $50,000, and, if he produced four bales per acre, he would get an additional $100,000.

Johnson produced 4.22 bales to the acre that year, earning Wayne in excess of $1 million, but the success was not obstacle free.

During the harvest, agents from the bank showed up in the field to repossess 10 Clari cotton pickers. “Louie marched over to the bank and signed a nearly $800,000 note so that they wouldn’t take the equipment,” Alice said.

Partners for life

Wayne was impressed by the success of his newfound manager, and the two decided to merge Wayne’s 4,000-acre farm with Johnson’s 6,000-acre farm and become partners.

“They had a running bet that if Louie was able to produce more than four bales per acre a year, he (Wayne) would buy him a Cadillac,” Alice said. “Every year but one Duke bought Louie a new car.”

Johnson renovated a room for Wayne to stay in when he and his family made trips to the Johnson residence. Often Wayne would come to the house to have Alice help him shave weight for an upcoming movie role.

“I would follow a diet plan from a book called the Diet Watchers Guide,” Alice said. “It was a sort of an old-time Weight Watchers program.” According to Alice, the real key to his weight loss was a specially designed bathroom in which every surface was mirrored except the ceilings and floors. “He always said being able to see his body from every angle helped him to drop the weight.”

While the cotton business treated the two men well, federal government cutbacks on water allocations in the 1960s, aimed at preventing Southwestern cotton farmers from putting others in the nation out of business, pushed the partners toward cattle.

Johnson and Wayne built an 18,000-head feedlot and soon expanded into cattle breeding with an operation in Springerville, Ariz., that covered more than 50,000 acres. At the Springerville location the two focused on raising the highest quality bulls and then auctioning them off at the 26 Bar Ranch near Maricopa. These annual auctions attracted hundreds of potential buyers to the area from across the nation.

“They were a big event back in the day,” Alice recalled.

In addition to the Springerville ranch, the feedlot near Maricopa expanded to 85,000 head, becoming the largest privately owned feedlot in the United States.

However, in 1974 housewives across the nation, enraged by skyrocketing beef prices, staged a brief but powerful boycott, sending the duo’s operation into the red.

“We lost millions,” Alice lamented. “It was amazing that Louie could just come to bed every night, close the door and not worry about a thing.”

To counteract the failing industry, Wayne and Johnson reduced the number of cattle on their feedlot to 8,500, but the bankers were not going to let Johnson give up on the business.

“They insisted he begin buying cattle despite being low on credit,” Alice said. “They told him to keep buying until they told him to stop.” Johnson began buying in January 1975 and by June had expanded the operation tenfold from 8,500 to almost 85,000 head of cattle.

Death of a legend

The partnership between the two men ended later that year when Wayne died of cancer, but early residents like Smith still have fond memories of him.

During his many trips to the farm Wayne would often drive through Maricopa, stopping at local businesses. “No one rushed him for autographs when he stopped,” Smith said. “He loved the kids and would stand all day signing things for them.” Wayne would also often head out to his favorite drinking location, the Table Top Tavern in Stanfield, and spend time with local farmers.

When Wayne died, Johnson decided it would be best for him to exit the business also.

“The Wayne children were going to sell Duke’s portion, so we decided it would be a good time to get out rather than getting stuck with a partner we didn’t know,” Alice said.

When the children were auctioning off items from Wayne’s estate, they surprised the Johnsons by calling them out to their father’s California residence.

Alice had first visited there many years before, falling in love with an extravagant chandelier Wayne had purchased in Europe. “It was so weird seeing such a beautiful chandelier in his home; it just didn’t fit his personality,” Alice said.

When they arrived for the estate sale, the children said they were going to vote on gifting the imported chandelier to Alice, and all seven voted in favor. “I was so happy I did a dance on the kitchen floor,” Alice said. Louie died of cancer in 2001, and Alice, now in her 70s, remarried a few years later. To this day she and her new husband live on the property that hosted John Wayne in Maricopa.

This story was first published in 2009. It was republished in the Fall Edition of InMaricopa the Magazine.

![Affordable apartments planned near ‘Restaurant Row’ A blue square highlights the area of the proposed affordable housing development and "Restaurant Row" sitting south of city hall and the Maricopa Police Department. Preliminary architectural drawings were not yet available. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/041724-affordable-housing-project-restaurant-row-218x150.jpg)

![Affordable apartments planned near ‘Restaurant Row’ A blue square highlights the area of the proposed affordable housing development and "Restaurant Row" sitting south of city hall and the Maricopa Police Department. Preliminary architectural drawings were not yet available. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/041724-affordable-housing-project-restaurant-row-100x70.jpg)