As Maricopa grows, one of its biggest assets is water supply.

The city sits on the Maricopa Stanfield Sub-basin aquifer, which includes 23,000 acre-feet of water, making it one of the biggest in the region. One acre-foot of water represents 325,000 gallons of water, enough water to serve three-plus houses for a year.

Water supply is cautiously monitored and maintained by Global Water Resources.

Jake Lenderking, the utility’s vice president of water resources, is quick to point out that while there’s a lot of water under the ground, it’s a finite resource.

“The groundwater is not really considered a renewable resource,” Lenderking said. “So, you have to be careful.”

“There’s a lot there, but not enough to waste.”

The Arizona Department of Water Resources, through its Assured Water Supply program, issues assurances for a 100-year supply of water. In most municipalities, developers need that assurance before they can begin construction.

Global Water Resources has 100-year assurance, not only because of the abundance of water in the ground, but due to water reclamation and conservation efforts, according to Lenderking.

Lenderking said GWR proved to the Department of Water Resources there is both physically available groundwater and a recycled water supply through its philosophy of total water management by using smart meters and recycled water.

The designation is particularly valuable when you consider that new 100-year assurances are no longer being issued.

The source

Maricopa sits on in the Maricopa Stanfield Sub-basin aquifer, which is quite a resource.

“We’re using about 7,000 acre-feet and we have 22,914 acre-feet in our designation, Lenderking said. “Is it good positioning? Definitely.

“It’s there, and it’s reliable. Not all areas have that. So, if you’re thinking about Pinal County and water supply issues, that’s one of the big ones.”

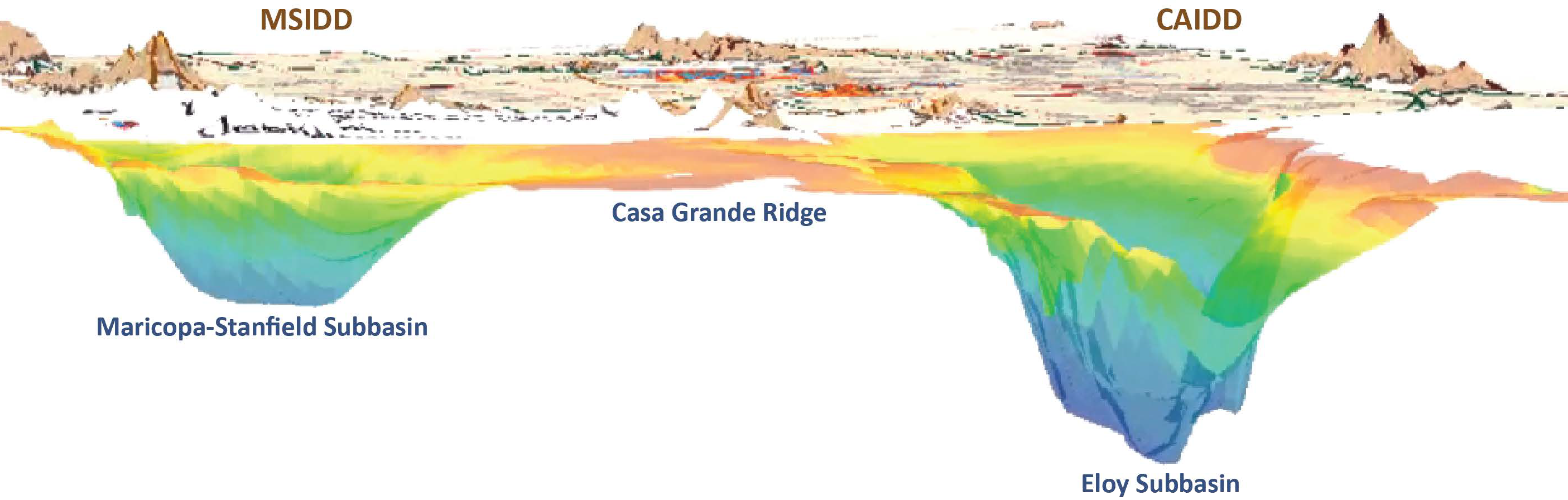

There are two predominant types of aquifers in Arizona — alluvial aquifers most often found in the valleys and fractured rock aquifers more prevalent in the mountains and foothills.

Alluvial aquifers are found under rivers and other bodies of water and, for the most part, have more water than fractured rock aquifers.

The Maricopa Stanfield Sub-basin is an alluvial aquifer that extends throughout the city’s current borders and beyond.

At some points, the aquifer is 3,000 feet deep. (That’s more than two-and-a-half Empire State Buildings.) But the most attractive part of this source is water can be found at surprisingly shallow depths.

“We have a well that’s only 65 or 70 feet below land surface,” said Jon Corwin, vice president and general manager of GWR.

Lenderking added in a desert state like Arizona amid a severe drought, many wells are 300-400 feet deep.

“Oh, it’s really variable,” Lenderking said. “It’s really going to depend on site-specific conditions in the greater alluvial aquifers. Think about the Greater Phoenix metro area and the Maricopa Stanfield Basins in and around Pinal, those are big alluvial aquifers, you know, the water table can vary in places.

“We are really fortunate where we’re at with the water table 65-70 feet below land surface. We use a lot of recycled water, which helps keep that water level up,” he said.

Lenderking said most of the water has been there for quite some time.

“It’s percolated over many, many years; hundreds, maybe thousands of years, and that’s a large part of the water that’s there today,” he explained. “Streamflow also recharges the aquifer. So, when the Santa Cruz and the Santa Rosa (rivers) run, they replenish and add to the aquifer. The Gila River adds to it. There’s also mountain front recharge where again, rainwater would go against the mountain at the foot of the mountains — it’s an area of increased recharge of the aquifer.”

Water makes it into the aquifer in other ways, too.

“There’s what I call incidental recharge,” Lenderking said. “The agricultural sector uses water. And that water doesn’t just stay in the root zone. Often, it goes past the root zone and percolates down to the aquifer. So, a portion of what the farm fields use ends up back in the aquifer, as well as in municipal and industrial applications or municipal settings.”

To a lesser extent, leaking lines and irrigation and other sources contribute a negligible amount of water.

“All those also contribute to the aquifer,” Lenderking said. “But the lion’s share of the water has been there for a very long time.”

Some utilities in other areas may recharge by putting excess water back into the aquifers.

It may sound like a straightforward operation to pump excess water back into an aquifer for later use, but it is a complex decision with potentially widespread effects.

“Citing research, large recharge facilities can be difficult,” Lenderking said. “For example, if you are going to put a lot of water in the aquifer and raise the water table, all the way to the ground surface, that could have negative consequences. That is why there is a permitting process for that.

“So, for example, if you raise the water level up into an existing landfill, you might bring contaminants out of the landfill and mobilize them into the aquifer.”

Global Water has received a permit from the Arizona Department of Water to recharge the aquifer with no risk to the environment. Although recharging is two or three years away, the utility will use its Groves Recyclable Water Management Facility to help with the process.

“We’ll store the water in the facility and then, when it’s needed for the recharge component, it’ll be available,” Corwin said. “We have the infrastructure there to do that.”

Enhanced beauty around the community

Driving around Maricopa, it’s sometimes surprising how a city in the middle of the desert can have so many ponds and lakes.

For example, when you flush a toilet, that water is treated to the highest non-potable standard, “Class A Plus” recycled water, and used to fill many local lakes.

Class A Plus water is clean enough water for irrigation and beautification projects, but it’s not treated to drinking water standards.

Corwin noted a good portion of that water comes from the Groves facility.

“Once we treat the wastewater Class A Plus recycled water, we send it out to the community. We also store some of it there and then that helps us with some of our distribution to other locations, some of the lakes that are on kind of that far south and west part of town.”

How much growth is possible?

Mathematically, the Maricopa Stanfield Sub-basin aquifer allotment can support a Maricopa that is three times its current population, but Lenderking was conservative when asked about it.

“We’re using about a third of our water supply,” he said. “But it is more nuanced than that. It is kind of a hard question to answer. It is based on the supplies and then the renewal and then the end of the renewal period.

“So, the short answer is there’s a lot of room for growth. Probably, doubling in Maricopa, no problem.”

City Manager Rick Horst thinks water, and Global Water’s management of it, has the city in a prime position to handle future growth.

“The private sector does it generally better and cheaper than local government or any government can,” Horst said. “They have been a good partner with us and they, through their efforts and through our efforts, have put together a Designated Water Supply, or DWS, which provides a hundred-year guarantee of water.”

Horst said every time the City approves a new subdivision or development, a 100-year DWS is attached to the project to prove sufficient water is available to support it for the next century.

“We have plenty of room to grow in the foreseeable future,” he said. “Now, long term, there are still issues, but the other reason we’re in a good place is, if you look at the maps, the groundwater is closer to the surface where we are than just about anywhere else in the state.”

Looking ahead

It’s difficult to tell what the future may hold, but Maricopa has one of the best water situations of any municipality in the state.

Part of that is because of the huge aquifer, but Global Water’s efforts to recycle water and to educate ratepayers also play big roles.

Corwin explained Maricopa has another feather in its cap.

“Of all the designated assured water supply providers, our use per capita is the second lowest in the Greater Phoenix and Pinal County area,” he said, referencing a recent Arizona Department of Water Resources report.

The lowest usage was found in the Apache Junction Community Facilities District, which has a heavy concentration of mobile homes on small lots that don’t require a lot of water.

The reductions in the flow of the Colorado River and cutbacks in surface water allowances to Pinal County farmers have made national news.

“Big picture, of course, we’re in a big drought,” Lenderking said. “Our water supplies aren’t directly affected by the Colorado River water supplies, but they are affecting our neighbors. Our agricultural neighbors are seeing a reduction in the amount of water coming out the Colorado River for their crops.

“I think, big picture, we are always concerned about the drought and having enough, so that is one area of concern. The other piece is that aquifer and its allocations. We must be mindful on how we grow and use up this resource.”

Until then, Global Water will continue efforts to educate, inform and motivate where possible, Lenderking added.

“We want to give tools to the customer,” he said. “We have our advanced metering infrastructure that will send an alert to a customer that they have a higher-than-normal usage. That really drives a lot of efficiency in how water is used as well, because people have tools to be efficient in how they use water, and people want to do that..”

And if education is not enough, Corwin pointed out there is a financial motivation.

“We also have a pretty innovative conservation rebate as part of our billing structure,” he said. “In the city of Maricopa, customers that use less than 6,000 gallons in a month, which is approximately the average usage for a residential user in Maricopa, receive a 60% rebate on their consumption charge.”

This story was first published in the April edition of InMaricopa magazine.

![MHS G.O.A.T. a ‘rookie sleeper’ in NFL draft Arizona Wildcats wide receiver Jacob Cowing speaks to the press after a practice Aug. 11, 2023. [Bryan Mordt]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/cowing-overlay-3-218x150.png)

![Maricopa’s ‘TikTok Rizz Party,’ explained One of several flyers for a "TikTok rizz party" is taped to a door in the Maricopa Business Center along Honeycutt Road on April 23, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-042324-tiktok-rizz-party-flyer-web-218x150.jpg)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)

![MHS G.O.A.T. a ‘rookie sleeper’ in NFL draft Arizona Wildcats wide receiver Jacob Cowing speaks to the press after a practice Aug. 11, 2023. [Bryan Mordt]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/cowing-overlay-3-100x70.png)