Alice Kulbeth Johnson-McKinney first traveled from Arkansas to Arizona in 1955 at age 15.

“My dad had a heart condition, and the doctor said, ‘If you lived in a warmer climate and didn’t work so hard, you could increase your life expectancy.’ He had a brother that worked for the mines in Globe, so we sold the house and everything and moved to Arizona.”

It was just the beginning of a remarkable life that included picking cotton, performing country music, waitressing, flipping houses before it was cool, marrying four times (twice to the same man), being caretaker to ailing spouses and standing centerstage in one of the most iconic friendships in Pinal County history.

“Oh, she’s a great lady,” said Paul Shirk, president of the Maricopa Historical Society. “And she has so many stories. Every time I talk to her, I hear a story I haven’t heard before.”

People like to ask her for stories about John Wayne, but she likes to share the full history as much as she can while she’s still here and can remember the details.

“There’s not too many of us left, the older farmers,” she said. “We’re getting old and passing on.”

In the 1950s, Johnson-McKinney’s father was a logger and took a little time to land a job with the Globe mining companies. Back in Arkansas he had played fiddle in a country band that also included 11-year-old Alice on upright bass and her little brother Larry playing mandolin/guitar. They had a regular gig on a local radio station. Based on that youthful experience, Alice and Larry landed jobs in Arizona before their parents did.

She marched into a Globe radio station and said they wanted to play on air and get paid.

“She said, ‘We can’t pay you unless you get sponsors,’” Alice recalled. “So, I went to town to a men’s store, and they said they’d be a sponsor. And I went to a furniture store, and they were a sponsor. We went back to the radio station, so they gave us a 30-minute program on Saturday mornings, and they paid us.”

She also landed a job as a car-hop at a foot-long hot dog place in Chandler.

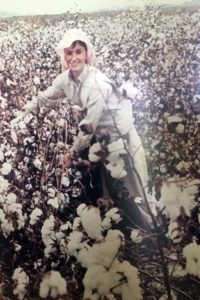

Johnson-McKinney lasted in Globe through six weeks of school before deciding to return to her grandparents in Arkansas and finish high school in a school with more amenities. She also picked a lot of cotton on their small farm, up to 300 pounds a day while daydreaming of being a movie star. After graduation, she returned to Arizona.

When she was 19 and Larry was 14, they went to California to make a record. While waiting for their own recording session, Alice ended up recording two lines of a commercial for a clothing outlet because the chosen model could not fake a southern accent. They drew the interest of a talent scout, but their parents were not prepared to quit their jobs in Globe.

By 1965, Alice was married and divorced with a 6-year-old daughter, Becky, when she was waitressing at Copper Hills Restaurant in Globe. The owner, local icon Danko Gurovich, set her up on a blind date with a much-older, well-to-do farmer named Louis Johnson. It definitely was not a meet-cute.

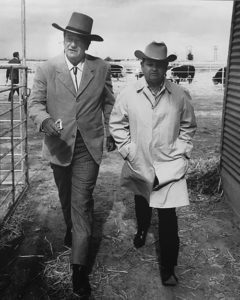

“I was supposed to meet Louis at Durant’s Restaurant in Phoenix. It’s an hour and a half drive from Globe, and I never had gone on a blind date, so I just decided not to go. I didn’t show up,” she said. “Well, apparently he had had John Wayne fly over and was with him at Durant’s. Louis was really embarrassed and took a lot of razzing from the Duke because I didn’t show up.”

Johnson and Wayne had been partners growing cotton in Pinal County since 1958. Widely dubbed the best cotton farmer in the state, Johnson grew up picking cotton in Arizona and bought his first acres near Stanfield for $50 an acre when he was just 19.

“The Anderson Clayton Company would buy the land for you,” Johnson-McKinney said. “You would agree to use his gins, and then you just paid them back.”

Johnson and Wayne eventually combined their neighboring properties, and Johnson managed the 10,000 acres.

By 1965, when Gurovich tried to be matchmaker, Johnson and Wayne were moving into the cattle business after the federal government cut back on water allotments for cotton. Able to grow cotton on only a section of his land, Johnson created a feedlot.

He and Wayne put together 50,000 acres for a grassland ranch near Springerville in Apache County and bought purebred Herefords, paying over $100,000 for a single bull. Wayne and Johnson were in the middle of the effort to construct the 26 Bar Ranch when Alice came into the picture.

The day after that failed blind date, Gurovich pushed Alice to call Johnson and apologize. “Out of sympathy, I made another date with him because he asked me to bring Becky along. So, I said, ‘That’s pretty smart.’”

That first date was to the ranch he and Wayne were putting together. “Everyone” had told Alice how smart Johnson was. While that was not her first impression, she said she soon learned “everyone” was right. Johnson was intelligent, wise and a heck of a farmer.

“He wasn’t a big man, but his heart made up for it.”

She dated Johnson for a while, but Becky’s father came back into the picture. She decided to try marriage with him again for Becky’s sake. Not only did it break Johnson’s heart, but it didn’t take. “You should never marry a person a second time, because the problems are still there.”

When she divorced again, Johnson was waiting for her.

“We were very compatible,” she said. “Before we got married, we talked about a lot of things. It seemed like everything that suited him suited me… We were able to converse about everything.”

Johnson-McKinney said a level of trust built because she would never take money from him while they were dating. “I had a job and I was able to pay my bills and I had my own house.”

She also worked at a bank for a time and at Roosevelt Lake Estates, where she waitressed.

She married Louis Johnson in 1969, and they moved to the ranch between Stanfield and Maricopa, where they were surrounded by cotton.

“When I first came here in ’69, I don’t think the road had been paved that many years,” she said of Maricopa. “It looked like Stanfield. It had a bar and a service station and a small grocery store.”

Never one to be idle, she got to work in the four-acre yard and planted trees all over the property. She wanted evergreens to remind her of the pines in Arkansas. She and her brother stuccoed the 17-year-old, block house, a large but modest home.

Still sensing she was bored and a little isolated as a young woman used to working, Johnson had friend Verna Cooper take his wife to a meeting of the Cotton Wives Club, part of the Arizona Cotton Growers Association. Under Cooper’s wing, Alice joined the club and eventually became president. She still maintains friendships from the group.

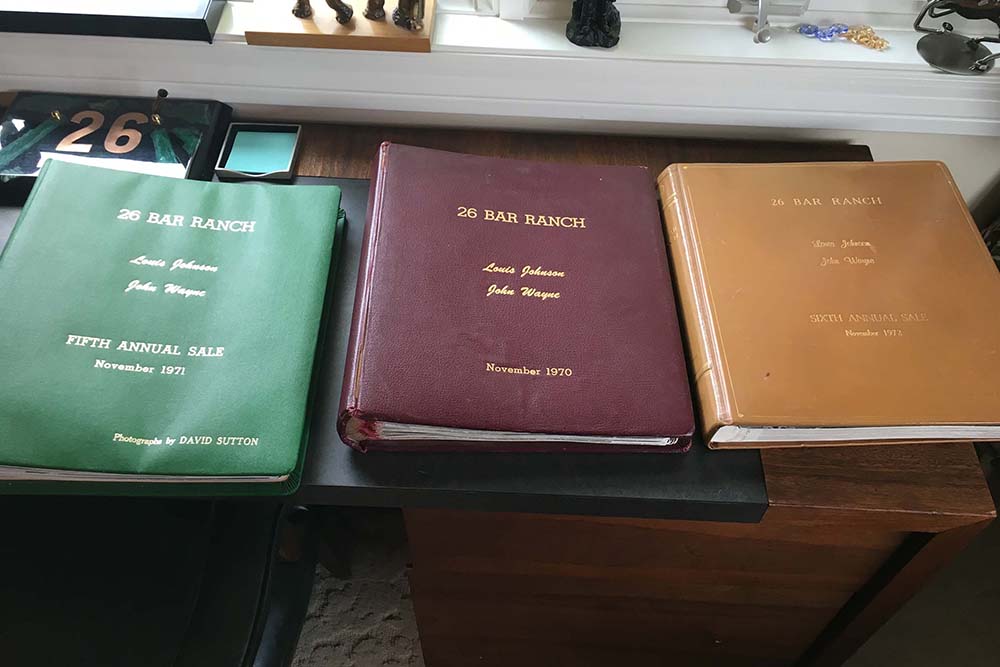

Johnson and Wayne had started their annual cattle sale in 1968 at the Stanfield farm. He and Wayne trucked bulls and heifers down from Springerville. The sale started small but grew to national renown.

“One year we had ranches represented from 37 states,” Johnson-McKinney said. “John Wayne being a partner didn’t hurt any, as far as people wanted to see him, but the cattle were very good. That took precedent over celebrities.”

Louis Johnson did not leave cotton behind.

“He stayed with it. He wasn’t playing golf. He wasn’t going on vacation. He was looking at it every day,” Johnson-McKinney said. “He would look at the cotton in the morning with the sun shining on it from one direction, and in the evening he would look at it with the sun from the west shining on it.

“He said anytime you see a shoot off the main stem and there are four cotton bolls in there, it means you’re gonna get four bales per acre.”

Each year, Wayne and Johnson had a bet that if Johnson produced four bales of cotton per acre, Wayne would buy him a Cadillac. If not, Johnson would buy Wayne a car. Johnson received a Cadillac every year but one.

They played high-stakes jokes on each other as well. When Wayne said the Johnsons could eat free at Danko Gurovich’s restaurant, Johnson took full advantage one evening. He made off with a case of vodka and boxes of steaks, shrimp and bacon.

“They didn’t have enough bacon the next morning to serve in the restaurant,” Johnson-McKinney said. “We had bacon. I had an aunt that lived down the road, and we took it to her, and she divided it with all her neighbors down the street.”

Johnson and Gurovich also pretended to buy a racehorse named Snickerbar Dan, giving Wayne a share for $12,500. The horse did not exist.

Still, Wayne trusted Johnson when it came to business.

“Louis saved him,” Johnson-McKinney said. “He was in financial duress. They were repossessing all the farm stuff. He bought this farmland and didn’t know what he was doing.”

She said Wayne was actually “pretty gullible” and could be suckered in by just about anyone with an investment scheme until he got in the habit of turning them over to Johnson first. They were, in fact, like family, each called “uncle” by the other’s kids.

Alice speaks of The Duke with great affection. She said he felt perfectly at home in Maricopa and Stanfield and at the Johnson house in particular.

“He loved coming here. He liked visiting with the people, with the locals,” she said. “Even when he came and it wasn’t bull sale time, we’d have some local people [like Donna and Jimmie Kerr] come out and have dinner. He liked the ranch and farm people.

“He was just like he is. He either was not an actor, or he was acting all the time. What you see on screen is just the way he is in person.”

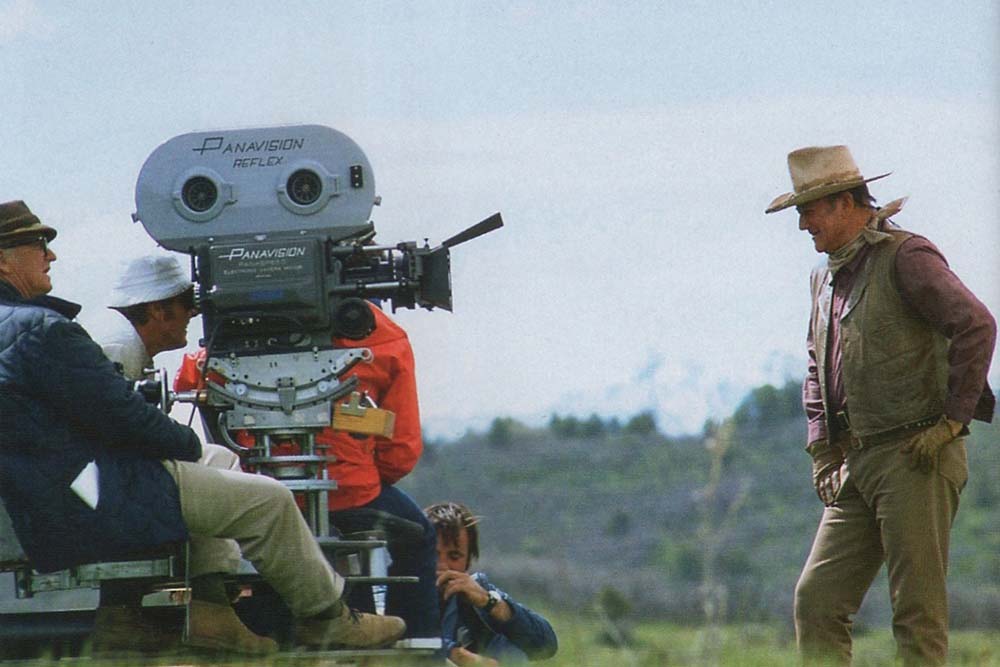

The Johnsons visited Wayne several times when he was filming on location, having dinner with him and Katharine Hepburn in Oregon during “Rooster Cogburn” and dropping in on him in Texas during “The Cowboys” and for the Houston premiere of “Hellfighters.”

Back at home, Alice still needed intellectual stimulation. She floated the idea of going back to college, but Louis couldn’t agree to that. So, when her stepson Johnny went off to New Mexico State University, she had him buy books for her.

“When Louis went to work at 4 o’clock in the morning, I would just read,” she said.

In the mid-1970s, when beef went into a slump, Alice and Becky started “flipping” houses. With money invested from the sale of her home after she married Johnson, McKinney bought a second house. She and Becky worked it into shape and sold it two months later for a profit.

“Becky and I flipped before flipping was flipping,” she said.

They continued that process through a series of houses as 50-50 partners. Then they decided to keep some of the houses they flipped to put up for rent as mines shut down around Casa Grande during a strike.

“Men were going to other states for work. Women were wanting to reunite with the family,” she said. “I could give them $5,000 for their house, and they would sign it over to us. We didn’t have to go and borrow the money. You could assume somebody else’s mortgage, back in that day. You can’t do that now.”

Word got around among those who were losing their homes in Casa Grande that Alice and Becky would buy it for $2,000-$5,000, and they wouldn’t have to ruin their credit.

“That was very lucrative, because they might have paid on that house 10-15 years,” Johnson-McKinney said. “That’s how Becky and I formed a business, and now she has rental properties.”

Alice gave her own house the works, too.

“The master bedroom had its own bathroom, but all the other bedrooms had to share a common bathroom down the hall, and I didn’t like that,” she said. “I made all the bedrooms bigger, and they have their own bathrooms.”

She had told Johnson what elements she might want if she built her dream house. That included a deck, a dome and skylights to see the stars.

He gave her carte blanche to do whatever she wanted to the house. The result is a unique ranch house that is both western and Hollywood. She maintains a John Wayne suite, but also has The Duke memorabilia spread throughout the house. There are two kitchens, though she declares she’s not much of a cook. There is a bar, a pool and a tennis court. There are also unique family paintings.

After Wayne died of cancer in 1979, the Johnsons began selling off some of their assets as well. Alice and Becky continued their construction business and built houses for all the kids in the blended family. Then, as the end of the century neared, Louis fell ill.

“One day, everything was normal, and the next day, it was never the same,” Johnson-McKinney said.

After a grueling battle, Louis Johnson died of cancer in 2001.

That left Alice taking care of much of their assets around the country including an office building in Montana. She also bought a home there. She had to travel to Billings with a nephew to deal with a legal issue concerning the office building. There, she met a local rodeo cowboy and truck driver named Verne McKinney, who had been single for 30 years and had just retired.

Dancing in the Northern Hotel, they hit it off quickly.

After a long-distance correspondence, Alice and Verne married in 2003. During 14 years of marriage, they did some world traveling, and Alice’s ring of acquaintances widened even more.

But life was never a breeze. Johnson-McKinney cared for her Alzheimer’s-stricken mother for the final three years of her life. Then cancer again hit home, taking Verne McKinney in 2017.

Alice continues to live independently but looked after. Her daughter lives in a house on the property, and there are laborers to help with upkeep.

She feels the housing developments in Maricopa inching closer and said she has had offers for her surrounding acreage. She now maintains 160 acres as a cushion.

“I won’t ever sell it,” she said. “This is my roots.”

This story appears in part in the January issue of InMaricopa.

![Shred-A-Thon to take place tomorrow An image of shredded paper. [Pixabay]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/shredded-paper-168650_1280-218x150.jpg)

![Shred-A-Thon to take place tomorrow An image of shredded paper. [Pixabay]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/shredded-paper-168650_1280-100x70.jpg)