Partnerships and relationships. Ensuring public safety. Unlocking full potential.

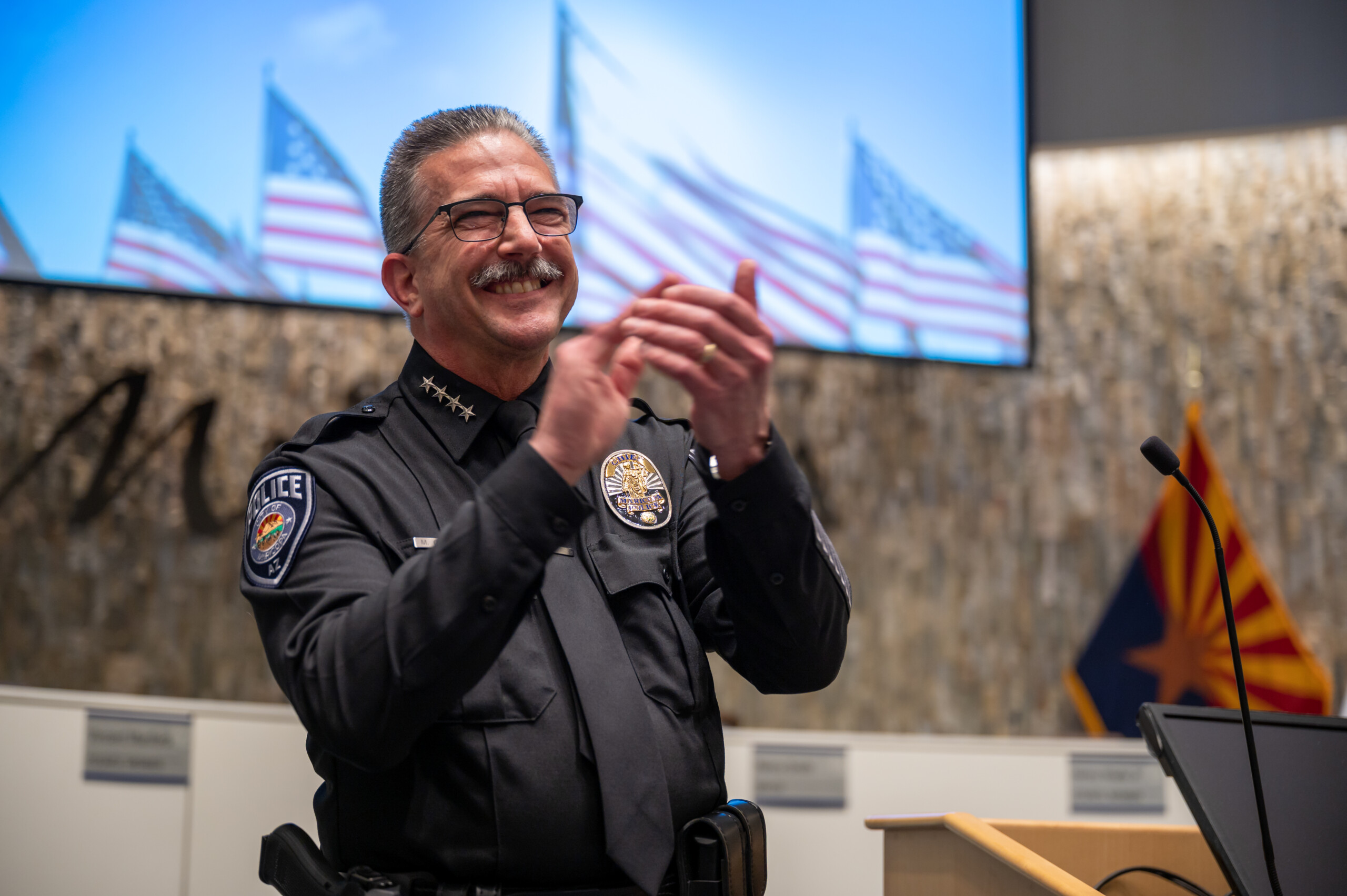

It all sounds good—and especially at the denouement of taking an oath of office—but in speaking with Maricopa’s new top cop, Chief Mark Goodman, one realizes his words were more than just bits of rhetoric for a speech.

These are intrinsic elements of his philosophies on policing and his intentions for the role.

“I want people to approach me and say, ‘hello,’ so I can get to know them and establish relationships and friendships in the community,” he said. “They can see me in settings other than being the police chief.”

Goodman vowed, “Through community partnerships and relationships, Maricopa Police Department will ensure public safety for those who live, work and play in this city and will be an integral part of unlocking the full potential of the city of Maricopa.”

The new chief, a lawman for three decades, sat down with InMaricopa to discuss law enforcement.

“Besides my family, it’s one of the great loves of my life,” Goodman said.

He made a commitment to serve Maricopa for at least 10 years, noting his ambition to be an approachable, hometown chief of police.

‘I want people to approach me and say hello’

One image from his swearing-in ceremony endures: a row of officers lined against a wall in City Council chambers, watching, smiling, waiting. It’s expected when any civil servant takes an oath of office, but as the chief embarked on a series of handshakes and hugs with officers, politicians and family members, the watching, smiling, waiting felt more profound.

Goodman noted his top priority is building relationships with his department and the community.

It might be a wave at the grocery store or being visible at public events. During his first month, Goodman threw out the first pitch at Maricopa Little League’s opening day and hosted town halls in the city’s neighborhoods.

“People feel like they can’t approach the chief of police. I don’t want to have that persona,” he said. “I want a persona where I’m friendly and people want to engage with me and with my officers.”

He says that is key in a community where he hopes to “do more listening than talking.”

“I want to listen to our community members and see what their needs are, then tailor our policing to those needs,” Goodman said. “We need to have a conversation. At the end of the day, our community members know their individual neighborhoods better than we do.”

That not only assists in creating a deeper sense of community for Goodman, but also highlights why he opted to move to town: It adds a greater sense of responsibility for safety in Maricopa.

“It shows you have a stake in the community,” he said. “When you live in the city in which you are responsible for public safety, it really brings it home for you. When your kids are going to school here or when your family is shopping in the same places, it’s really important.”

Community policing is not ‘soft on crime’

Community policing is a buzzword that grew out of the 1990s.

Initial phases took the form of police creating and attending neighborhood-watch meetings, but Goodman said this often led to a significantly greater presence of officers than community members. He lamented the lack of collaboration between departments and the communities they served, calling the ordeal “frustrating.”

“Policing is kind of the same, regardless of where you are,” he said. “It’s sort of the ‘how’ in what we do that changes, and that falls into my community-policing philosophy. How do we deliver those services?”

For Goodman, part of that translates into a need for a greater level of input from residents. Combined with more traditional versions of crime-fighting, it ultimately will lead to creating a safer city, he believes.

“To me, the next iteration of community policing is building those relationships, giving people a sense of safety. It is calming fears and providing those custom police services … to our community members so they feel like they’re listened to, that they have a voice and that they’re an active participant in the process,” Goodman said. “It’s not just us providing a service.”

All that led to Goodman addressing one elephant in the room.

A native Californian, Goodman is deeply aware of the opinion most Arizonans exhibit toward their neighbor to the west. In fact, the results from an unofficial poll in December showed more than a third of InMaricopa.com readers disliked having a Californian in the position. Some reader comments on social-media posts further drove this point home, equating it with “gun grabbing,” and parroting “don’t California my Maricopa” comments.

But Maricopa residents shouldn’t translate his roots with being “soft on crime,” Goodman maintains.

“I come from an agency that had a very strong community-policing philosophy, and the city of Maricopa also has a very strong community-policing philosophy,” Goodman said. “Community policing is not soft on crime at all. It’s still making arrests when appropriate and engaging the criminal element when it comes to our attention, then taking appropriate action to keep our community safe.”

Instead, he said, that dedication to community-building equates to a more proactive police force that has an inherent knowledge in how to address issues important to its community.

Transformations in police work since 1994

Approaching a third decade in his career, Chief Goodman has witnessed a profound shift in policing and its culture. Crime trends, the ways in which departments evolved their crime-fighting methods and the internal culture of law enforcement differ greatly from when Goodman first wore a badge in Los Angeles County in 1994.

While property crime remains high around the country, among the key changes Goodman has observed is watching technological crimes slowly take greater precedence over violent street crimes. Consider the difference between wire fraud and scams over mugging and open-air drug dealing.

“As technology progressed, criminals everywhere have adjusted to use technology to commit crime,” he said. “Most of what we thought about street crimes in the ’90s was stuff taking place on the street… That’s gone away for the most part because of technology. People can use technology to communicate with one another, meet up and then disappear. It’s created a lot of anonymity.”

Goodman sees the proactive elements of community policing assisting with that, where engaging in public-education efforts may act as preventive measures. He also wants to focus on how his department can use technology in its policing methods.

One of those changes includes a greater emphasis on body-worn cameras.

“Body-worn cameras are a great tool for our officers. They help us a lot in terms of being accurate and accountable,” Goodman said. “Accountability is big for me, and I want to make sure that our people are adhering to our body-worn camera policy. We have engaged in some tech to help us with that.”

According to Goodman, the department is upgrading its camera equipment and will use software that automatically activates cameras rather than rely on officers to remember to turn on their cameras. For example, when an officer flips on the flashing lights during a traffic stop, cameras would activate and begin filming. In most instances, the technology also would enable video to roll back as long as one minute, increasing context.

“We’ll be able to see areas for improvement and then hold people accountable for those areas of improvement,” Goodman said. “I look forward to being able to do that. I have experience in increasing those numbers at my former agency, so I’m encouraged by that.”

‘We had to … see things that no other people should see’

Discussing those changes also led Goodman to point out one more significant change in law enforcement he’s seen.

On-the-job stress takes a serious toll. Officers statistically experience significantly higher rates of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, burnout and anxiety-related mental-health conditions, according to the National Alliance on Mental Health. Additionally, nearly 1 in 4 officers had suicidal thoughts in their lifetime, and that rate is higher with smaller departments, or those with the equivalent of at least 20 officers. Maricopa’s police force has 81 sworn officers.

The shift to focusing on wellness creates officers who can better serve their communities than those who “feel the pain and feel the trauma of those things they see and do every day,” Goodman said.

The Maricopa Police Department offers services with mental-health professionals for its officers. Reminders of this service are sent quarterly. It’s a major benefit for residents, according to Goodman.

“I think, in the long run, it will pay dividends for our employees and also for the people of Maricopa. They’re going to get officers who are happy, are well mentally, are well physically, are well emotionally,” Goodman said. “(Those officers) are ready to provide a high level of service and to help people solve problems, because that’s what we do.

“People don’t call us to tell us they’re having a great day. They call us to tell us they’re having a problem and they need help solving that problem. That’s why we exist. If having that mental-health program helps our officers to remain empathetic, then that’s a huge help.”

Maintaining or redeveloping empathy is crucial for officers to be effective in problem-solving, according to Goodman. It helps them look through various lenses to better engage with the people.

“All of our officers are very empathetic when they’re hired. But over time, there’s a tendency to forget and to become less empathetic,” he said. “We sometimes feel the pressure to respond to calls for service and sometimes we don’t do a great job of just engaging with people and letting them know that we care.”

To Goodman, maintaining that empathy not only assists in service calls but can also help community relationships with police.

“We’re guardians of our community, but we’re also members of our community, so being empathetic helps to humanize us,” Goodman said. “We don’t just go home and plug ourselves in at night. Police officers are not robots. They have lives, they have feelings, they have families. It’s important for the public to understand that.”

Unlocking potential in Maricopa

A city still forging its boundaries, Maricopa’s population is on a path to grow approximately 4% each year through 2030, the year it’s expected to reach 90,000 residents. Providing quality police service to the city is a topic that consistently sits at the front of Goodman’s mind.

“One of my primary concerns is making sure that we right-size the department, that we have enough police officers to give a high level of service without having too many or too few,” he said. “You need to be strategic about that and make sure that we’re operating within our budget, that we’re being responsible with our tax revenues. We owe it to our community to do that, and that’s a really difficult balance.”

However, Goodman is encouraged by working with other city leaders in achieving equilibrium.

“The good news is the city has a very skilled leadership team,” he said. “It’s a team effort, it’s not just me evaluating this or analyzing that. It’s a team of people who are doing that.”

Those elements had always been essential to the position.

It also noted the selected police chief would be expected to serve as an active contributor to its senior leadership team.

All of this cycles back to what ultimately drew Goodman to Maricopa: its potential. The potential of the city, its police department, its officers and its residents.

“Part of what attracted me here was ‘come build the city with us, come unlock the full potential of the city of Maricopa,’” Goodman said. “It’s really interesting to be part of that experience. That’s not something you get everywhere.”

For Goodman, that includes using advancements in policing, boosting officer wellness and helping to grow Maricopa into a city centered on safety and stability.

“People choose where to live and establish businesses based on safety,” he said. “One of my goals is to always address issues about being fearful. We want people to have a feeling of safety here in town. We want them to be able to go about their business and feel like they’re safe.”

![Affordable apartments planned near ‘Restaurant Row’ A blue square highlights the area of the proposed affordable housing development and "Restaurant Row" sitting south of city hall and the Maricopa Police Department. Preliminary architectural drawings were not yet available. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/041724-affordable-housing-project-restaurant-row-218x150.jpg)

![Affordable apartments planned near ‘Restaurant Row’ A blue square highlights the area of the proposed affordable housing development and "Restaurant Row" sitting south of city hall and the Maricopa Police Department. Preliminary architectural drawings were not yet available. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/041724-affordable-housing-project-restaurant-row-100x70.jpg)