His story begins less than a month after Black Tuesday, America’s economic disaster that incited the Great Depression.[quote_box_right]“He’s always served without fanfare, under the radar, wanting no recognition – just wanting the pure joy and knowledge that things will be better.” Kelly Anderson[/quote_box_right]

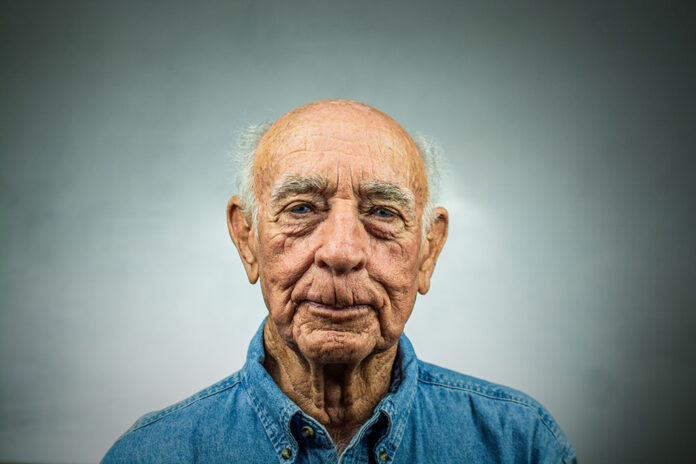

Oliver Anderson, 88, was born a Phoenician on his family’s farm near Southern and 19th avenues in 1929. Life for all Americans then was a challenge. But the effects of the Wall Street crash were less noticeable to those who worked the ground.

“We grew our own food, and what you didn’t grow, you traded with your neighbors,” Anderson said.

From farm to island, Anderson later spent two years in Japan on a U.S. Air Force base.

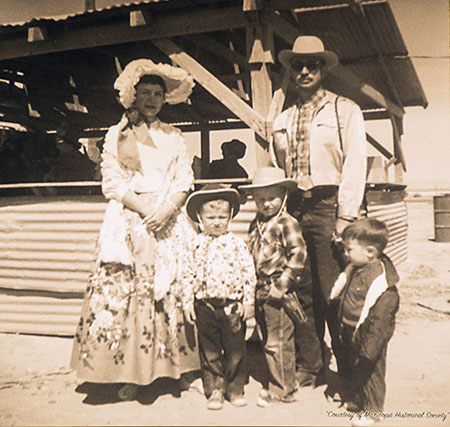

In July 1954, the young cosmopolitan moved to Maricopa in the sweltering heat to work on a farm co-owned by his father and a business partner. Anderson-Palmisano Farms, started in 1949, grew cattle, cotton, grain and alfalfa.

Services in the dusty community were primitive – there were no residential phones and roads were paved with dirt. The 25-cycle electricity pumped currents so low, utility customers were bathed in beams of blinking lightbulbs.

“Maricopa was out in the country, but if you’re working seven days a week, time goes pretty fast – very rapidly,” Anderson said.

The rural town was inhabited with working people spread far from each other by the agriculture industry that provided most of them a living.

Townspeople saw each other once a week, usually at school functions or Headquarters Café.

Newsprint didn’t cover the happenings in the town yet, either. Residents visited Postmaster Fred Cole or the barber to stay informed.

“The haircut you received depended on his mood of that day,” Anderson said. “When you went in to get a haircut, that’s where you got the scoop.”

Those who made their mark in the early days didn’t do so without challenges, according to longtime Maricopa resident and farmer John Smith. Settling the rugged, desert land and transforming it into fertile ground was not always simple for many working in the often unforgiving agribusiness.

“Oliver has been successful out on that farm when very few people were,” Smith said. “Things got tough, but he managed to wade through — a few of us did — most didn’t.”

The Andersons made their contributions to the activities and culture in Maricopa, too.

Hermina, Anderson’s wife of 62 years, employed her musical prowess while directing dinner theaters at the school in the 1980s. She provided piano lessons to children and served on the school board.

With a small populace and no formal government, Maricopa pioneers, like Anderson, began a life of service to the community that would span decades.

With the Maricopa Rotary Club, Anderson helped the community in its effort to build a swimming pool. The annual Stage Coach Days celebration was launched to help fund it.

For 10 years Anderson served on the Maricopa School Board, before it became a unified district.

In the early 1980s, Anderson was asked to serve on an advisory committee to the University of Arizona dean of the burgeoning Maricopa Agricultural Center.

Anderson has served on the Pinal County Active Management Area Ground Water Users Advisory Committee for 45 years; the board of directors for the Arizona Cotton Growers Association for 35 years; the Pinal County Farm Bureau Board of Directors; the Arizona Farm Bureau Board of Directors and many more.

It’s a service to others he can’t seem to stop. “When I get on, I can’t get off,” he said, eyes glimmering.

Leadership seems to run in the Anderson family.

Anderson’s son Kelly was the first publicly elected mayor in 2004 and has himself served on many boards and committees, including a six-year appointment to the Arizona Department of Transportation’s State Transportation Board.

The eldest son of Anderson’s four children, Kelly Anderson attributes his civic success to his father.

“He’s always served without fanfare, under the radar, wanting no recognition – just wanting the pure joy and knowledge that things will be better,” Kelly said.

The quiet management style of the Anderson clan has lent well to their business.

Kelly is the third generation to manage the family farm.

The 600-acre operation on Farrell Road has evolved to specialty crops – producing dry flower products for big-name brands like Hobby Lobby, Pottery Barn and Michael’s.

Oliver and Hermina’s three other children – Troy, Lynn and Wendy – specialize in the arts, electronics and medical care.

It’s that kind of success of his own children and other Maricopa schoolchildren that routinely has Oliver steeped in pride, according to Kelly.

“A lot of (students) come back to Maricopa to have a career and do something. It’s a nice return on your time invested,” Kelly said.

Kelly’s wife, Torri Anderson, has served as president and board member of the Maricopa Unified School District for years.

Maricopa’s legacy is embedded in the souls of its people – who as Oliver Anderson said – consistently come together for the good of the community through flood, fire and fundraising.

“It’s the folks that came here initially and said, ‘Hey, by golly, regardless of if it’s dusty, regardless of it’s hot, regardless of if it’s a long way from town, this is my home, I want to live here,’” Oliver said.

This story appears in the September issue of InMaricopa.

![Elena Trails releases home renderings An image of one of 56 elevation renderings submitted to Maricopa's planning department for the Elena Trails subdivison. The developer plans to construct 14 different floor plans, with four elevation styles per plan. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/city-041724-elena-trails-rendering-218x150.jpg)

![Affordable apartments planned near ‘Restaurant Row’ A blue square highlights the area of the proposed affordable housing development and "Restaurant Row" sitting south of city hall and the Maricopa Police Department. Preliminary architectural drawings were not yet available. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/041724-affordable-housing-project-restaurant-row-218x150.jpg)

![Elena Trails releases home renderings An image of one of 56 elevation renderings submitted to Maricopa's planning department for the Elena Trails subdivison. The developer plans to construct 14 different floor plans, with four elevation styles per plan. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/city-041724-elena-trails-rendering-100x70.jpg)