Kent Volkmer, a Republican, was elected Pinal County Attorney in 2016 after several years in private practice. He sat down with InMaricopa to talk about criminal justice and some of the issues his office is tackling.

What is a day in the life of the county attorney?

A lot of meetings, as opposed to being in the courtroom every day. I would say any given day, probably three or four different meetings with various entities, various agencies. Typically, Monday is my most consistent day getting kind of caught up on stuff that happened on the weekend. On every Monday afternoon for about two hours, I meet with my chief of criminal, my chief deputy, my chief of staff as well as my head of civil, and we talk about kind of issues that are upcoming issues and preparing for what’s going on.

You rarely do appear in court. How many attorneys does your office have?

I believe we have 45 current attorneys.

In what circumstances do you go to court?

Honestly, there’s very, very few reasons. I actually am handling a trial coming up soon simply because it was a very unique situation. I felt comfortable handling the matter and didn’t want to put somebody else in that position just because of the unique circumstances surrounding it. Otherwise, it’s normally just saying, ‘Hi,’ to people. Actually, formally appearing on the record, I can’t tell the last time that happened.

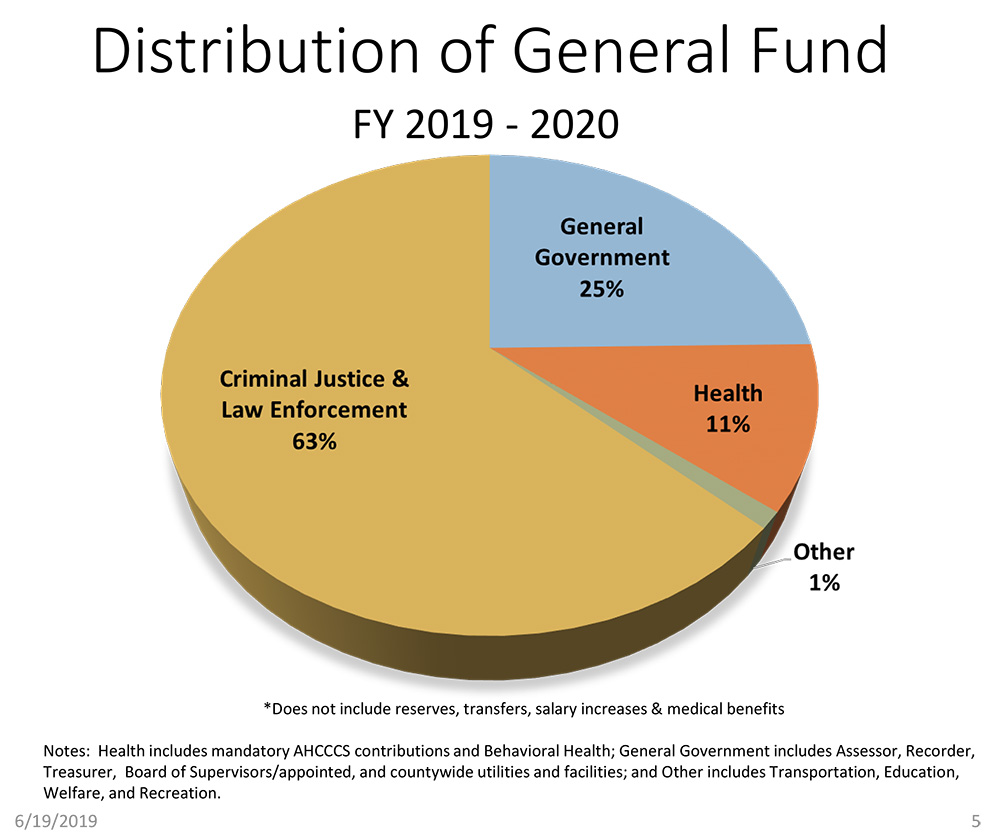

A giant chunk of the county budget (63 percent) goes to law enforcement, courts and prosecutions. What are your office’s costs?

Personnel. Ninety percent is just people.

What are your opportunities for keeping costs down?

There are some. Oh, yes, we absolutely do have grants. We have the JAG Byrne grant [Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant], which is federal prosecution grant. We have a number of other grants that come forward. Actually, in this current budget cycle here, I was able to request, and our Board of Supervisors gave me, a grant coordinator, so we’re actually going to have a dedicated person in our office that’s looking at those costs to see if there are any grants available. There are a number of federal grants. A lot of time when you do a pilot program or you do programs that other people aren’t doing, the government’s willing to give you those resources to get kick-started. That’s kind of how we kick-started our diversion program. The state gave us about $400,000 to really offset the costs to the taxpayer and then try to make the program sustainable.

How is the Diversion Program working?

I’m thrilled with it. About 2.5 percent of our felony cases are diverted and a bunch of our misdemeanor cases. So about 600, 650 cases in a given year are diverted. What that means is people that we identify as not being a danger to society but made a dumb decision, a poor decision, are given the opportunity to complete consequences, do a risk assessment, hopefully fix whatever caused them to make that bad decision in the first place, and then the charges are ultimately dismissed, so there’s no conviction on their record.

What are you enjoying most about your job so far?

That’s a good question. I think the ability that it gives me to really effect change in our community. There are a lot of different things I’ve been able to do, one of the things I’m very proud of is, under Arizona law when we’ve talked about marijuana specifically, prosecutors are given the opportunity to charge it either as a felony or as a misdemeanor. It’s sort of our decision. What I discovered is my office is making these decisions often without the input of law enforcement, without the input of the people who are on the ground interacting with these people. One of the things that we did is we flipped that and we allow the officer at the scene to make the initial decision and then we sort of review it on the back side. What we’ve discovered is that’s reduced about 750 felony charging of marijuana year-over-year. The other thing that does is significantly reduces the bookings at the jail, which is a huge cost savings to everyone. Just those types of things where we get to sit back and ask, ‘What’s the right thing to do? What’s the best thing for our community? What’s the safest thing we can do?’ This job gives me that opportunity. It’s a powerful position, but it’s also a humbling position and I love it.

Speaking of marijuana, if recreational marijuana were legalized in the state, how would that impact your office?

At the felony level, it would not have nearly the full impact. I have not had the opportunity to review all of the proposal, but I do know that they limit the amount of personal possession to one ounce, which I do like. Two and a half ounces is about a hundred joints. To say that’s personal possession has always kind of struck me as a little bit odd. So, they’ve reduced that number. There’s still going to be a gap between 18 and 21; I’m not sure how they want to treat that. There’s also still going to be above that threshold, how they’re going to handle it. Most of the time, when we’re prosecuting at the felony level, it’s going to be the sale amounts; it’s going to be the huge amounts. Depending on how that law is actually written, whether it’s passed, it’ll have some impact but not the impact it would have had, say, three or four years ago.

What is your philosophy when it comes to plea deals in cases of violent felonies?

Pleas are a necessary evil. About 98 percent of our cases resolve via plea. And that’s for a number of reasons, one of which is, frankly, the financial aspect of it. You mentioned most of our county budget goes to law enforcement. Our budget’s about $12 million of taxpayer dollars that we receive. If we were to try many more cases, that number would necessarily have to increase correspondingly. It’s not necessarily a dollar-for-dollar increase, but it would have to go up. So we do have to use those pleas. I’m much more comfortable using them in the non-violent cases. It’s the violent ones that are much more difficult, because part of my obligation is to make sure that I keep this community safe. I’m not going to say we don’t offer pleas, but typically on those murder cases, those real high-end cases, all of those pleas are normally staffed. That means the attorney assigned has reviewed it along with their supervisor and then usually my chief deputy and myself and the team to look at those and figure out what an appropriate resolution is.

In the violent cases, would it that state feels there’s a vulnerability in the case more than the cost?

It’s not a vulnerability in the case; it’s typically a vulnerability to the community. The law gives us the ability to put people away for a really long time. The issue is if someone has a violent propensity and they commit this offense, the law says, ‘Well, presumptive sentence, for example, is 10.5 years.’ And we say, ‘We’re going to give you 3.5 years.’ My concern is if that person gets out in 3.5 years and then commits another violent offense, how do I look that victim in the face and say, ‘Yeah, I know the law told me this is what I was supposed to do, but it was really expensive, so I put finances above your safety.’ Sometimes it does have to do with vulnerability of cases, but typically it’s what do we really need to do to make sure our community’s safe, and what does this person really need? Is this somebody who, again, maybe has a drug addiction, maybe has some violent tendencies? Is this somebody that we can put in prison and have them come out on probation to give what they need to return to our community, or is this somebody that we have to put away because we can trust them to follow our societal laws to keep us safe?

What have you accomplished so far and what would you like to accomplish before the end of this term?

Seems like I should know the answer to that question. I think the things that we’ve done have really been incremental. I don’t know that there’s been a lot of wide-sweeping, giant modifications that we’ve done. One of the things we’ve done is we’ve tried to streamline the process. I think my greatest accomplishment is, I believe, that my office is looking at each case as an individual case. We’re not looking at it as numbers. We’re not looking at it as paperwork, but these are humans that we’re trying to make an individualized decision on, to do what’s best not only for that person but for the community as a whole. That’s a mindset. It really is, because it’s easy to say, ‘No, no, this is what we’re going to do, and we can just run through these cases very quickly.’ It takes more time, it takes more willpower, it takes more emotional investment to look at an individual case and say, ‘Yeah, I know that these are both burglaries, but we need to treat these different because of the impact on the community, because of the impact on the victim, because the actual sort of criminal mindset that’s involved.’ I think my office is doing an exceptional job of carrying out that mission.

Did you have anything that you’d specifically like to accomplish by the end of this term?

I don’t know that I do. Our job is to see justice done. It’s not to gain convictions. It’s not to have a trial rate or put so many people in prison or put so many people on probation. Our job is to do everything we can to keep this community safe. Our community, we’re safer than any of the other big communities. The likelihood of one of our residents being victimized is about half the rate it is if you live in Maricopa County. It 2.5 times more likely in Pima County to be victimized. We’re safer than Yavapai County and Prescott, we’re safer than Yuma, we’re safer than all the other counties. My job is to make sure we keep that train headed in the right direction.

What has been your biggest challenge as county attorney?

The biggest challenge, I think, is finding the balance between what the law says we should do and what individualized justice is and figuring out what is truly in the best interest of our community. I’ll give you a perfect example. If you have two prior felonies and you’re caught selling drugs, let’s say a very small amount in hand-to-hand sales. You had half a gram, which is half an M&M, and you sell half of that amount to your friend for just the amount you paid for it. That’s a Class 2 felony. Under our laws, if you have those two prior felonies you should be serving 15.75 years in prison. I think most people would say 15.75 years is more than necessary. It’s sort of that ‘The strictest justice is the greatest injustice.’ But the question is, how far do you pull that back? What’s the appropriate amount? What’s really fair and just under those circumstances? Because, again, if somebody’s harmed or that person gets high and drives in a vehicle and kills somebody, it’s really hard to look those victims in the eye and say, ‘Well, I’m sorry, I took a chance and I was wrong.’ Maybe letting that person on probation isn’t right, but there’s got to be a balance, and I’m really trying to figure out what that balance is, what the community wants. I’m a representative of the community; I’ve been elected by the community to represent the will of the community. We are a representative democracy; we are a republic. We are not mob rule. So there is this delicate balance of trying to figure out what is really the thing that we should be doing for our community. What should we be doing that is in the interest of all the residents that are here? And then you also have that second sort of balance. What are other counties doing? Because we have a few different cities now that are sharing borders. We have Apache Junction that is on both sides. We have Queen Creek that’s on us both sides. We have kind of Oracle/Oro Valley/Catalina area there. We also have Marana who’s now growing. Depending on what side of the street you’re on should not make a huge difference in what your consequences are. You shouldn’t get probation if you’re on one side and prison on the other. That becomes justice by geography. That’s just as fundamentally flawed.

This story appears in part in the September issue of InMaricopa.

![MHS G.O.A.T. a ‘rookie sleeper’ in NFL draft Arizona Wildcats wide receiver Jacob Cowing speaks to the press after a practice Aug. 11, 2023. [Bryan Mordt]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/cowing-overlay-3-218x150.png)

![Maricopa’s ‘TikTok Rizz Party,’ explained One of several flyers for a "TikTok rizz party" is taped to a door in the Maricopa Business Center along Honeycutt Road on April 23, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-042324-tiktok-rizz-party-flyer-web-218x150.jpg)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)

![MHS G.O.A.T. a ‘rookie sleeper’ in NFL draft Arizona Wildcats wide receiver Jacob Cowing speaks to the press after a practice Aug. 11, 2023. [Bryan Mordt]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/cowing-overlay-3-100x70.png)