Last month, AARP CEO Jo Ann Jenkins wrote in the group’s bulletin “the system for helping people who can no longer care for themselves is broken and costly.”

This is important because, as she noted, “Nearly 70% of American who reach age 65 will someday require help from others to get through their day. On average, women will need help for 3.7 years, and men for 2.2 years.”

Unfortunately, the system providing these services is deeply flawed.

Only a small number of Americans have the resources to obtain long-term health care needs. Medicaid has programs — for those who qualify on the other end of the economic spectrum — that can provide a bed, food, nursing care and enough support to live with a modicum of dignity and comfort.

The problem is the “gigantic middle,” as termed by Nancy LeaMond, AARP’s chief advocacy officer. They include many Americans who can’t qualify for Medicaid or cashflow their own caregiving either at home or in an institution. Their care is likely to come from an unpaid family caregiver. Some 53 million Americans of all ages devote a portion of their day to this support.

More than 1 in 5 Americans are caregivers and 61% of them also work, with 24% of these caregivers caring for more than one person. About 61% are women and at least 45% of them have suffered at least one financial impact. With 10,000 boomers turning 65 every day through 2030, the need for unpaid family caregivers will increase.

The toll is great because of the flaws in the systems intended to assist them. The support needed from employers, government or the healthcare industry falls short or is too confusing to obtain. This is further complicated by the nature of what happens during a medical crisis. Family members get thrown into chaos, changing schedules as they relate to home, career and, of course, finances. Most family caregivers aren’t prepared to deal with that new set of tasks.

Since the Older Americans Act of 1965 established the U.S Administration on Aging, the federal government has sought to help older people maintain maximum independence in their homes and communities. Most services are delivered through State and Area Agencies on Aging. Locally, the Pinal-Gila Council for Senior Citizens does a great job of providing services and programs to county residents. It’s also a great first stop to learn about available services.

But these services don’t reimburse lost salary or out-of-pocket expenses for caregivers, who spend about 24 hours per week providing homecare. A June 2021 AARP study found 78% of family caregivers spend more than $7,200 per year on care. Moreover, they get no training on how to provide proper homecare support. Yet, they carry the medical support system on their backs though their own health often suffers.

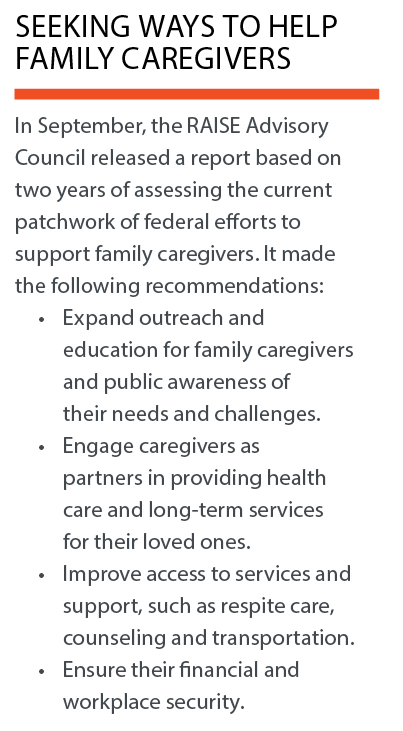

In 2018, Congress and President Donald Trump passed the Recognize, Assist, Include, Support and Engage (RAISE) Family Caregivers Act. It directed the Secretary of Health and Human Services to develop a national family caregiving strategy to identify support opportunities by communities, providers, government and others.

Ron Smith is a living-in-place advocate, a member of the Age-Friendly Maricopa Advisory Committee, a Certified Aging-in-Place Specialist and a Certified Living in Place Professional.

This column was first published in the June edition of InMaricopa magazine.

![Senior Info/Expo draws hundreds Clinical Liason Elaina Young of Compassus Hospice and Palliative Care speaks with an attendee at the Senior Info/Expo at the Maricopa Library and Cultural Center on Jan. 20, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/spencer-012024-senior-info-expo-web-01-218x150.jpg)

![He has the power: Weightlifter doesn’t let age or others’ opinions stand in his way Mack Hodges. [Bryan Mordt]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/BCM_8517-scaled-e1690992804625-218x150.jpg)

![Shred-A-Thon to take place tomorrow An image of shredded paper. [Pixabay]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/shredded-paper-168650_1280-100x70.jpg)

it’s a pity that this is all that they can now offer on long-term terms, I wouldn’t be satisfied with this either, I don’t understand why someone should get more or less ?! And yet care for the https://allnursinghomes.info/ elderly should be the same in cost and availability!