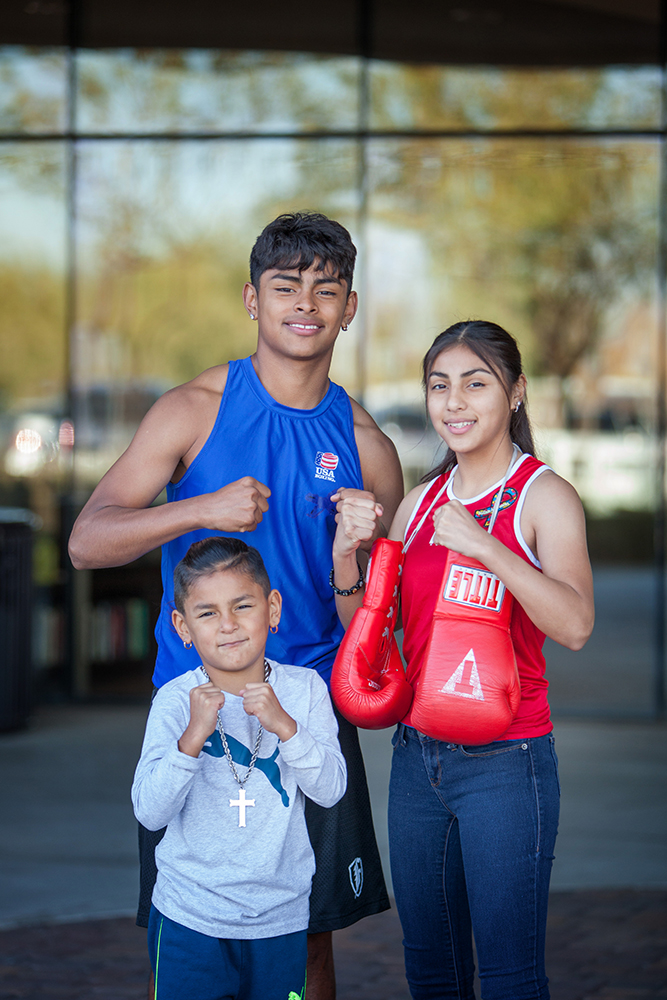

When 14-year-old Alezet Valerio won her division in the national Silver Gloves boxing tournament, it was just another step in her plan to become a professional fighter.

Boxing in the intermediate bracket (95 pounds, age 13-14), she was part of a crowd of boys and girls punching it out in Independence, Missouri, after winning state and region titles. Alezet (aka Chomina) defeated Malaya Wohosky Jan. 31 in a split decision. The next day, she defeated Araceli Gudino unanimously to win the championship belt.

Then she shared a hug with Araceli, a competitor she had never seen before facing her in the ring.

The Maricopa Wells Middle School eighth grader has been training as a boxer since she was 6 years old. She started competing at 10.

“I’d see my brother doing it and I went and tried it out myself,” Alezet said. “Ever since I first sparred, I loved the sport and just fighting, being in the ring, it’s just a good feeling.”

She is closing in on 40 bouts, only six of them losses. Alezet is ranked second in the nation in her bracket.

“At school I can’t get in fights, so to hit someone else feels good,” she said. “And when I win, it feels good because of all the hard work I did, it all paid off at the end.”

Her mother Abby Garcia said she was not just representing the western region or just Arizona but Maricopa, their new home.

The Valerios moved from Phoenix to Maricopa in October. Taking in nephews, they needed a bigger house. They qualified for a loan and found a five-bedroom house in Maricopa Meadows.

[quote_box_right]

USA Boxing on youth safety

- Teach boxers ways to lower the chances of getting a concussion.

- Enforce the rules of the sport for fair play, safety and sportsmanship.

- Ensure boxers avoid unsafe actions such as:

> Using their head or headgear to contact another boxer

> Making illegal blows or colliding with an unprotected opponent

> Trying to injure or put another boxer at risk for injury - Tell boxers you expect good sportsmanship at all times, both in and out of the ring.

[/quote_box_right]“It’s different from where we grew up, way different,” Alezet’s father and coach Thomas Valerio said. “She went for a run the first day and when she came back, she said, ‘It’s so clean out here, the grass is green, it smells so good, the roads are nice.’”

By contrast, he grew up in a tough area of Phoenix where he and his brother fell into gang culture.

“Growing up, we were always fighting in the streets,” Valerio said.

That is how his brother died at age 20, already the father of three. Valerio himself was a father by 17. While starting to think what kind of life he wanted for his own family, the streets were still calling.

“I didn’t want my kids to live how we lived,” he said.

Suburban pastimes like softball were hardly available. The closest athletic complex was a boxing gym. Valerio remembered his father, a former boxer in Mexico, taking him to the gym starting when he was 8 and thought it would be a good way to focus his kids’ energy.

“So, I took them every day out of the streets and into the gym. And they had school and homework,” he said. “I just tried to keep them off the streets as much as possible.”

Soon he was teaching them what he remembered from his father. The group of his own kids and nephews became Big Bro Gym. He trains the youngsters in his garage.

While building up his older sons, he got an earful from Alezet, who told him to pay attention to her, too. And for good reason.

“Actually, the girls are way tougher,” he said. “She’d get a bloody nose, and she’d have drops of blood coming down and she’d keep going.”

Alezet said the Maricopa kids are “soft” compared to those she knew from the Phoenix neighborhood. She attended Kuban Elementary School. Though seemingly slight of build, she is strong and intimidating when necessary.

“The first time I sparred it was against another girl. She was known at the gym we were at,” she said. “And they were like, ‘Oh, you’re gonna get beat up. You’re not gonna do good against her.’ When I sparred, I was punching her and punching her. And when she started crying, that’s when I knew I could do it.”

American Academy of Pediatrics frequently condemns youth boxing for its concussion dangers, saying the risks outweigh the health benefits. A joint statement from AAP and Canadian Paediatric Society reads, “Participants in boxing are at risk of head, face and neck injuries, including chronic and even fatal neurological injuries.”

Valerio said he teaches his young boxers to fight defensively.

“I teach them how to be smart fighters, not brutal fighters,” he said. “I teach them a lot of defense. She’ll wear you down. She runs five miles a day. Her cardio is off the roof. She’ll wear the girls down in the first round and then in the second round she just takes them apart.”

Alezet trains every day with her father and her uncle Hector Valerio.

“There are like no days off at all,” she said. “We hit the bags, we run. Some days we work on cardio and strength. Other days we work on legs and stuff. It’s like my life. I love it. I don’t do any other sports. I’ve never done any other sports besides boxing.”

She said she is good in math, reading and physical education but considers school boring. Boxing gives her motivation to make straight A’s.

“If I get anything lower than a B, I can’t compete at all.”

Her dad talks about her wicked hook, but Alezet said her strength is her focus. “Keeping my mind focused on the fight. That’s why some kids quit, because they don’t have their mind focused on it. They quit because they want to have fun and they don’t have the discipline.”

While her oldest brother wants to turn professional at 17 and her youngest brother wants to start competing at 8, Alezet’s immediate focus is joining Junior Olympics. That could get her closer to her long-range goal of making the U.S. Olympic boxing team, preferably in 2024 when she is 18. That entails traveling long distances, even internationally, to fight in qualifying bouts.

That is expensive, and they have to carefully choose competitions and engage in fundraisers to keep the dream alive and keep hanging championship belts on the garage walls.

Alezet enjoyed the camaraderie of the Silver Gloves competition. She noticed it expanded from the Arizona boxers all cheering for each other to all the Region 8 boxers representing Arizona, Nevada, California, Hawaii and Utah cheering each other on.

“At the end, we all do it to get the same thing.”

This story appears in the March issue of InMaricopa.

![Elena Trails releases home renderings An image of one of 56 elevation renderings submitted to Maricopa's planning department for the Elena Trails subdivison. The developer plans to construct 14 different floor plans, with four elevation styles per plan. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/city-041724-elena-trails-rendering-218x150.jpg)

![Affordable apartments planned near ‘Restaurant Row’ A blue square highlights the area of the proposed affordable housing development and "Restaurant Row" sitting south of city hall and the Maricopa Police Department. Preliminary architectural drawings were not yet available. [City of Maricopa]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/041724-affordable-housing-project-restaurant-row-218x150.jpg)