EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the last in a series of articles dealing with the Massacre of the Oatman family in 1851 and those who survived it. A few days after leaving Maricopa Wells, the Oatman family encountered a party of 19 native men. The natives bludgeoned and stabbed to death Royce and MaryAnn, the parents, and four of their seven children. Lorenzo, 15 was clubbed on the head, thrown off a 20-foot embankment and left for dead. Olive, 14 and 7-year-old Mary Ann were taken to the village of their captors and treated as slaves for a year, after which they were sold to the chief of the Mojave tribe and his wife.

The two girls were treated very well by the Mojaves, but there came a season of famine and Mary Ann died of starvation. Olive was later returned to white society, where she learned her brother Lorenzo had survived the massacre and made his way back to civilization. The reunion between the two surviving Oatmans made headlines across the west.

With the permission of Olive and Lorenzo, a pastor named Royal B. Stratton wrote a book about the massacre and the events following it. The book is filled with distortions and sensationalism, and years later, when Olive married, her husband burned every copy he could get his hands on. However, the revenue from the book enabled the siblings to attend preparatory school.

Later, they did a lecture tour to promote book sales. After about two years, Lorenzo grew tired of retelling his traumatic story and moved on. He married and began a new life in Minnesota as a farmer. By all reports, Olive was a good public speaker, and she seemed to enjoy the lecture circuit. For nearly six years, she made a very good living traveling around the country lecturing about her experiences.

Let us back up, now, and view Olive’s story from her perspective:

After an arduous 10-day trek across the Arizona desert to Camp Yuma, where the camp commander told you your brother Lorenzo is alive, news that gave you such an emotional shock you fainted, you are finally, weeks later, reunited with your only living family member. The emotion you both feel is so strong neither of you can speak for nearly an hour.

But life goes on. After all the drastic changes you have been forced to endure, you are faced now with another you must adapt to living in the society of your own people. You have nearly forgotten how to speak your native tongue; you can no longer read or write.

People close to you observe how you seem to suffer, as though torn between two worlds: that of the Mojaves who treated you as one of their own, and this civilized world, which was yours before your family was slaughtered.

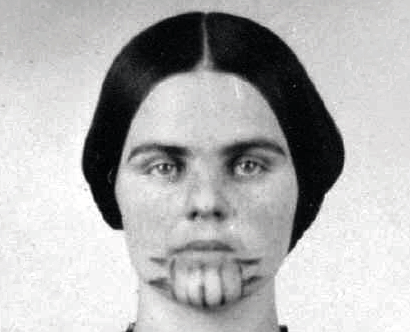

You wear a veil wherever you go to hide your chin tattoos, and when you speak face to face with someone, you have the habit of covering your lower face with your hand.

In 1864, eight years after your celebrated return, you meet and marry John Brant Fairchild, a wealthy rancher. You will never have to work again. You, who once were a slave to a native tribe, now have servants who do all the work. You, who lived in a tiny hut and wore only the bark skirt of a Mojave woman, now have a fine, two-story Victorian home. You wear expensive clothes. You, who nearly died of hunger during the famine that took the lives of countless Mojaves, along with your beloved little sister, Mary Ann, have food and money in abundance.

Those closest to you report you do not sleep well. You walk around the spacious grounds of your home in the darkness, often weeping softly. It has been speculated you left a husband and at least one child among the Mojaves, but you have never spoken of them. On the other hand, you never bear children in your marriage to John Fairchild, a fact that may indicate you are unable to conceive. No one knows but you.

The diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder does not yet exist, but it would be unusual indeed if you did not suffer from it.

You speak of the Mojaves in the highest terms, especially the chief, his wife and their daughter, who adopted you into their family.

You help out at a local orphanage, no doubt remembering how you yourself were orphaned. You and your husband adopt and raise a 3-week-old girl. You begin suffering from severe headaches, eye pain and deep depression, at times being bed-ridden for weeks at a time. These symptoms, which are likely related to your post-traumatic stress disorder, will plague you for the rest of your life. In 1903, at the age of 65, you die of a heart attack.

Your sorrows are over now, but the world will never forget the girl with the blue tattoos.

C.M. Curtis, American Western author and historian, is the best-selling author of 11 books, including eight westerns. His books can be found on Amazon or at CMCurtisAuthor.com.

This story was first published in the January edition of InMaricopa magazine.

![Maricopa’s ‘TikTok Rizz Party,’ explained One of several flyers for a "TikTok rizz party" is taped to a door in the Maricopa Business Center along Honeycutt Road on April 23, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-042324-tiktok-rizz-party-flyer-web-218x150.jpg)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)