The first time Marlena Robbins ate magic mushrooms, it wasn’t to see music or hear colors at a jam band concert. It was to cope with sobriety and trauma.

“I grew up in a home with domestic violence, addiction and child abuse,” she said. “I developed toxic habits and turned to alcohol and started abusing it.”

Talk therapy helped some. But she needed chemical succor.

“I felt it wasn’t going deep enough,” she said. “It wasn’t touching the core of what I needed but couldn’t verbalize.”

Some of her loved ones suggested trying psilocybin mushrooms to help process her trauma. One evening, she drank a shroom smoothie — and began to experience waves of colors, euphoria and an acceptance of her past.

“I remember lying on the floor and looking up at the ceiling and seeing these rainbow octagons coming at me, and it was beautiful,” she recalled. “Some of the imagery was scary. I said, ‘Thank you for presenting yourself, goodbye.’ And then they were gone.”

Alex Willbanks, a Navy veteran from Mesa, had a similar experience following his struggles with prescription medications to treat the post-traumatic stress disorder he developed in combat.

“A friend suggested I try mushrooms and it was calming,” he said. “I felt at peace and ease, and even the next day I felt better. It did more in one good evening compared to months of prescription drugs.”

Experiences like these inspired Arizona state Sen. T.J. Shope to blaze a path for legalizing psilocybin mushrooms for clinical use through Senate Bill 1570. For the Republican representing Maricopa, the idea emerged from a morning news segment.

A few months ago, Shope watched as billionaire entrepreneur Bob Parsons touted psychedelic drug-assisted therapy to help him recover from the trauma of his 1969 tour as a Marine in Vietnam.

Parsons’ story awakened a new passion for Shope, who also serves on the senate’s Health and Human Services Committee.

“Mushrooms in general have allowed [Parsons] to mentally come home from Vietnam all these years later,” Shope told InMaricopa. “I watched that interview with a lot of interest and I thought maybe we ought to consider at least just looking into it, not necessarily even thinking that I was going to run legislation.”

‘Another tool in the toolbox’

If there’s anything the pandemic did for Americans, it made people more aware of their healthcare options and become more open to alternative treatment options, according to Shope.

“People with PTSD have told me they’ve tried all these different prescriptions that don’t work, or they don’t like taking pharmaceuticals,” he said.

That includes people like Willbanks, who said his medications left him feeling “pretty numb.”

“I was on everything from standard antidepressants to different types of sleeping aids to help me sleep through nightmares,” he said. “They all left me feeling awful and pretty numb to just about everything. It wasn’t great.”

Studies on psilocybin taken with talk therapy show benefits in treating anxiety, depression, PTSD and substance abuse disorders. One study from Johns Hopkins University showed just two sessions could alleviate symptoms for up to one year.

Treatment options for Arizonans living with serious mental illness or substance abuse issues are few, according to Josh Mozzell, president of the Psychedelic Association of Arizona and a mental health attorney.

“People living with major depression, bipolar disorder and PTSD have a lifetime diagnosis and a lifetime of medicine,” he said. “Right now, once you get a diagnosis, you see your doctor every three months and you take a pill every day for the rest of your life, but you don’t necessarily get any better.”

SB 1570 would allow doctors to have an additional option for patients.

“Doctors currently have heavy drugs in their toolkit, like Xanax, Zyprexa, OxyContin,” he said. “This bill would allow them to have another tool in their toolbox, whether its psilocybin or, eventually, MDMA.”

“It was unthinkable, like, how could this be happening,” Mozzell said. “And then the studies on bipolar II and PTSD, all this stuff is a revolution in mental health.”

Playing catchup

Those results aren’t surprising to Robbins, a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Berkeley’s Center for the Science of Psychedelics and a member of the Navajo Nation.

Psilocybin mushrooms, peyote and other psychedelics have a long history interwoven in the ceremonial practices of Indigenous people. For example, the Mazatec in Oaxaca, Mexico incorporate teonanacatl — their word for the psilocybin mushroom, which translates to “the flesh of God” — into their ceremonies.

“They have used these medicines forever and know how they’re supposed to be experienced,” she said. “Western medicine is playing catchup trying to figure out what Indigenous people have known forever in how to experience these medicines for healing.”

Paired with the songs and prayers led by medicine practitioners in ceremonies, the use of psychedelics helps correct a physical, mental or spiritual imbalance in the patient.

“Ceremonies are created because we’re opening ourselves up for healing and the medicine people are there to sing certain songs and say specific prayers because they’re navigating us,” she said. “They are there to help us get where we need to go with the medicine and then bring us back.”

Robbins said part of that catching up includes understanding the respect users need to show the medication.

“Psilocybin mushrooms are a medicine that’s meant to help a person when they’re experiencing something difficult,” she said. “We have to give them as much respect and honor as we can because [from an Indigenous perspective] these medicines have spirits with them; they’re the Holy People and we’re asking them for help.”

A lesson from marijuana

Shope said the state legislature learned a lot from legalizing medical and recreational marijuana use over the years. That includes the difficulty of adjusting voter-approved initiatives.

“Mainly, when the voters pass something, the legislature really can’t change anything,” he said.

Mozzell agreed.

“Marijuana has been a nuclear bomb that has gone off in mental health because we cannot regulate it,” he said.

A handful of pot-related bills typically go through the House and Senate each year, but few advance to the governor’s desk. Shope said this includes bills meant to better regulate testing of marijuana products for public consumption.

“Even small fixes like that require three-quarters vote and [can] only further the intent of the law,” he said. “It’s as impossible as can be, which is why you’re probably not going to see any changes even with acknowledgment of those in and outside the industry.”

Shope’s 15-page bill legalizing medicinal magic mushrooms outlines thorough training protocol, licensure and regulations on use of mushrooms in a medical setting.

Most notably, it limits patients to consuming psilocybin only at a licensed psychedelic-assisted therapy center and only under the supervision of a staff member or medical director.

“It does not legalize the use of psilocybin outside of a clinic, and only under the care of a doctor,” said Mozzell, who assisted in drafting the original version of the bill. “It does not decriminalize psilocybin, and it doesn’t allow microdosing.”

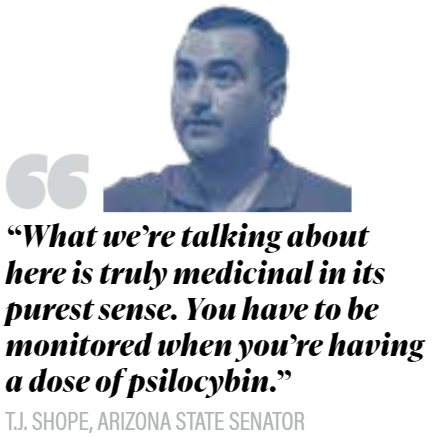

For Shope, the bill emphasizes the medical purposes of psilocybin, not the recreational ones.

“What we’re talking about here is truly medicinal in its purest sense,” Shope said. “You have to be monitored when you’re having a dose of psilocybin. It’s entirely clinical at this point in time.”

With Oregon and Colorado recently legalizing psychedelics like mushrooms, Shope and Mozzell remain optimistic Arizona could follow suit.

“It is coming. Psychedelics are coming just like marijuana to every state in 10 years,” Mozzell said. “We’ll see them legalized or decriminalized and we have to do it in a way that protects the citizens of Arizona against the potential risks.”

Path to legalization

Shope introduced the bill Feb. 5 with a first reading on the Senate floor and it swiftly moved through the Health and Human Services Committee and additional Senate readings.

The bill has so far passed the Senate with bipartisan support and cleared health committees in both chambers. Opposing votes came from Shope’s party mates Sen. Anthony Kern and Rep. Barbara Parker.

As of mid-March, the bill has yet to pass the House. If it clears that hurdle, it can be sent to the governor’s desk for her autograph or veto stamp.

Mozzell is gunning for Gov. Katie Hobbs’ signature. Full-throated Democratic support of Shope’s bill in the state legislature is a good sign.

“I’m just hoping we can get it out of the House and to the governor’s desk soon,” Mozzell said. “Then we can start getting the advisory board together, creating the training, getting the public educated.”

For shroom the bell tolls

When it comes to eating magic mushrooms, most Maricopans say, “No way.”

In a February InMaricopa.com poll of 400 Maricopa residents, more than half opposed any efforts to legalize mushrooms, even in a medical setting.

Roughly 1 in 6 said they would like to see the fungus be approved for medicinal use only, like a new take on Arizona’s famous Proposition 203 in 2010. That voter initiative legalized cannabis for medical use only, approved by 50% of the state population, a decade before recreational pot became legal.

About one-third of Maricopans said shrooms should be legal for recreational use.

What treats what

In the U.S., psychedelic-assisted therapy took off in the mid-20th century after the advent of LSD.

However, such efforts were quickly put to bed with the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, which effectively rendered these drugs illegal with no “accepted medical use” by the DEA.

Here’s a look at a few psychedelics undergoing studies for treating various mental illnesses:

Ketamine: This synthetic drug affects the glutamate neurotransmitter, which scientists believe may be responsible for mood regulation. Created as an anesthetic in the 1960s, ketamine only recently gained FDA approval for treatment-resistant depression.

MDMA: Better known by its street names, ecstasy and molly, this is a popular drug at raves and parties. The drug releases neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine, which can affect emotions, memory and attention. Researchers have spent the last decade using MDMA-assisted therapy to treat post-traumatic stress disorder and social anxiety.

Mescaline: This is the main component found in peyote, a cactus native to Mexico and the American Southwest that binds to serotonin receptors in the brain. Some research has shown mescaline-assisted therapy is effective for drug and alcohol addiction and depression treatment.

DMT: This ingredient is found in ayahuasca, a medicinal plant found in Central and South America, creating a quick and short-lived experience described by many as religious. The drug has undergone studies in treatment for depression and Alzheimer’s disease.