![Pima County Medical Examiner Andre Davis, medicolegal investigator supervisor at the Pinal County Medical Examiner’s Office, gives a tour of the facility. [Bryan Mordt]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/BCM_1836-696x463.jpg)

Top death investigator André Davis’ breath lingers visibly as he unhinges the cooler door.

Some of the bodies are intact. Some faceless remains yearn to be named.

Inside the Pinal County Medical Examiner’s Office, a porthole beckons the eyes to more body bags, identifiable only by strings of numbers scribbled on top. They lie serried on steel shelves like motionless soldiers in the barracks.

The head, stomach and feet undulate with canvas folds, teasing what’s inside.

Davis hauls open the door. A puff of frozen air carries a distinctly sweet — yet foul — smell that assails the senses.

In death, the bodies are frigid. Yet in the final moments of life, many suffered fatal heat.

In Maricopa, there’s a dark side to the sunshine.

Longest heatwave on record

Maricopa — and the Southwest in general — are experiencing the hottest summer on record this year.

While daily temperatures didn’t top a 122-degree July afternoon more than three decades ago, central Arizona experienced its longest-lasting excessive heat warning ever, according to the National Weather Service.

Daily high temperatures were consistently 110 to 117 degrees for 31 consecutive days.

High pressure prevented monsoon storms from entering the region, bringing about a generational weather event.

Rain showers, which were unprecedentedly few this year, are the medicine that treats the desert’s summer fever, said NWS meteorologist Sean Benedict.

“High pressure allows the temperature to warm up a lot more than usual,” Benedict told InMaricopa. “High pressure is associated with heat; low pressure is associated with storms.”

Another contributing factor: Unusually warm overnight lows.

In July, nights rarely dipped below 90 degrees, which prevented the area from properly cooling, said NWS meteorologist Chris Kuhlman.

In greater Phoenix, this equated to a monthly average temperature of 102 degrees, making July the hottest month on record. The second-hottest month took place in August 2020, when the average temperature was 99 degrees.

That seemingly innocuous 3-degree tick proved deadly, according to medical experts.

Death by heat

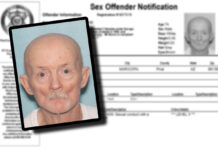

The Pinal County Medical Examiner confirmed 14 heat-related deaths through midsummer. The office predicts about 40 heat-related deaths by the time the hot season is over.

At least two occurred in Maricopa. The first fatality came June 21, the second, July 21.

The county’s numbers varied in previous years — 25 in 2020, 18 in 2021 and a whopping 32 in 2022. Last year, most deaths occurred in July, with 11 taking place over a two-week stretch.

This is not unusual, according to Davis, the PCME investigations supervisor.

“I believe July and August are historically the months we see the most heat-related deaths,” Davis said.

Data from the last three years shows that to be true for July. The exception was 2021, where June and August had higher totals than July.

On July 28 of this year, PCME had 15 examinations with pending toxicology reports to further clarify all causes of death. However, Director and Chief Medical Examiner John Hu said he expects nearly all to list heat as a contributing, if not primary, factor in the death.

“Most of those 15 will end up as hyperthermia, or heat-related deaths,” Hu said July 28. “This July, we had eight cases total confirmed, so it will at least double from last year.”

Davis said many die while attempting to live without air conditioning for a short time.

“I can’t tell you how many scenes I’ve been to where you suspect heat is a factor,” he said. “The family says the person’s air conditioning went out two weeks ago, but they didn’t have the funds to get it repaired or they don’t have someone to assist them in fixing it. That ultimately either led to or contributed to their death.”

Circumstances of a heat death

Sifting through the medical examiner’s extensive database of heat-related deaths over the last few years quickly shows it doesn’t discriminate among races, sexes and ages in Pinal County. The youngest victim was a 19-year-old white man in Red Rock last year. The oldest, a 92-year-old Black woman in Casa Grande the year before.

However, some trends emerge.

Older adults with underlying conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes or cirrhosis, are more likely to die in the heat.

“They have a lower tolerance, so the heat and the disease contribute to each other,” he said of people with underlying health conditions. “Usually, it is an unfortunate situation, like they are in a home without air conditioning.”

Most often, these occur in homes that aren’t cooled properly.

Long shifts of outdoor work in the heat and using alcohol or drugs in a non-air-conditioned environment are commonplace, too.

How a heat death occurs

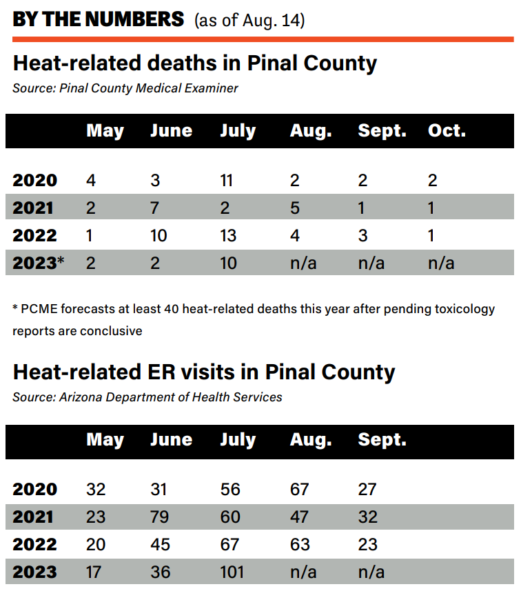

No matter the victim or location, each scenario bears a common likeness: hyperthermia setting in from exposure to the desert sun’s sweltering rays, or an overheated house.

Hyperthermia occurs when the body overheats and can no longer cool itself — typically setting in when the body exceeds 104 degrees due to environmental factors.

Early warning signs include thirst and headaches. This can lead to dizziness, weakness, muscle cramps or vomiting, all indicators of heat exhaustion, according to Exceptional Community Hospital Medical Director Lionel Lee.

Left untreated, the result is often heatstroke.

“They may start to have neurological conditions where they’re confused or unresponsive,” Lee said. “That’s when it becomes heatstroke.”

Other symptoms include hallucinations, seizure and coma. In the worst cases, this leads patients to the medical examiner’s walk-in freezer.

“While a clinical doctor will see more moderate cases, we only see the fatal cases,” Hu said.

Investigating and determining death

Not every body arrives at the medical examiner’s office.

“There’s certain stipulations under state law that make someone a medical examiner’s case,” Hu said.

An Arizona law requires the medical examiner to get involved when a death is sudden, violent, suspicious, unexplained or accidental. Heat deaths typically fall under the accidental category.

This begins with law enforcement reporting a death and investigators arriving at the scene.

“The most important factor we need to know is in what environment the body was discovered,” Hu said. “Was it outside? Was it in a room without air conditioning?”

Investigators examine circumstances and medical history, photograph the body and note the temperature in hopes of telling the story of what happened to the decedent. The body is then, ironically, transported to the cooler at the medical examiner’s office.

Instead, examiners often test electrolyte levels found in blood or, more often, in pockets of fluid in the eyes.

“That sometimes can shed light on the person’s electrolyte status when they died,” Hu said. “For example, if he’s severely dehydrated, a certain number from the test will tell us that. Or if the person sweat a lot and did not drink too much electrolyte fluid, we can tell that as well.”

These tests may take three months to return. Heat death investigations tend to be lengthy, especially when much of the body has decomposed, Hu said.

Once the toxicology report is available, the medical examiner will list the most obvious cause of death. If several factors are present, he will list them all.

“A 72-year-old with heart disease walking in a hot environment for 30 minutes, his heart probably won’t keep up,” Hu said. “One may have contributed a little more or a little less, but we say they all contributed to death. They worked together.”

The calendar may say summer ends in September, but the emblematic seasonal temperatures in Arizona can continue well into October. Experts recommend taking precautions to prevent heatstroke and death.

“I think some people downplay the heat of Arizona and Mother Nature in general,” said Lee, the hospital director in Maricopa. “People get caught up in activities and they just don’t realize how hot it is until it’s too late.”

During the hot season, NWS meteorologists continuously recommend staying indoors as much as possible, drinking more water than usual and dressing in lightweight clothes.

Lee agrees with these recommendations.

“You have to stay hydrated and take these illnesses seriously,” Lee said. “It can be very serious, especially if you don’t get help right away. I always tell patients, don’t hesitate.”

For Hu, living and working in the desert can quickly become a death sentence for anyone.

“When a person is subjected to extreme heat for a long period of time, it will take a toll on just about anyone,” Hu said. “That heat really kills.”

This story was first published in the September edition of InMaricopa Magazine.

![City gave new manager big low-interest home loan City Manager Ben Bitter speaks during a Chamber of Commerce event at Global Water Resources on April 11, 2024. Bitter discussed the current state of economic development in Maricopa, as well as hinting at lowering property tax rates again. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-041124-ben-bitter-chamber-property-taxes-web-218x150.jpg)

![3 things to know about the new city budget Vice Mayor Amber Liermann and Councilmember Eric Goettl review parts of the city's 2024 operational budget with Mayor Nancy Smith on April 24, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-042424-preliminary-budget-meeting-web-218x150.jpg)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)