During the past decade, the City of Maricopa has leaned on three far-reaching, collaborative, highly expensive projects with hopes of transformation.

One, the grade-separation of State Route 347 at the Union Pacific tracks, was completed last year. Another, the improvement of SR 347 from Maricopa to Interstate 10, is more reliant on other entities like Arizona Department of Transportation, Gila River Indian Community, Maricopa Association of Governments and Arizona Supreme Court.

The last, though less talked about, may have a broader impact on economic development. That is the North Santa Cruz Wash Regional Flood Control Project.

“This has been an on-again, off-again project for over a decade,” City Manager Rick Horst said. “When I got here, it kind of stalled out. So, I kind of re-energized the process. It’s really convoluted to explain.”

The plan is now at an important stage as the City awaits cooperation from Gila Riva Indian Community before it takes the concept to the federal level.

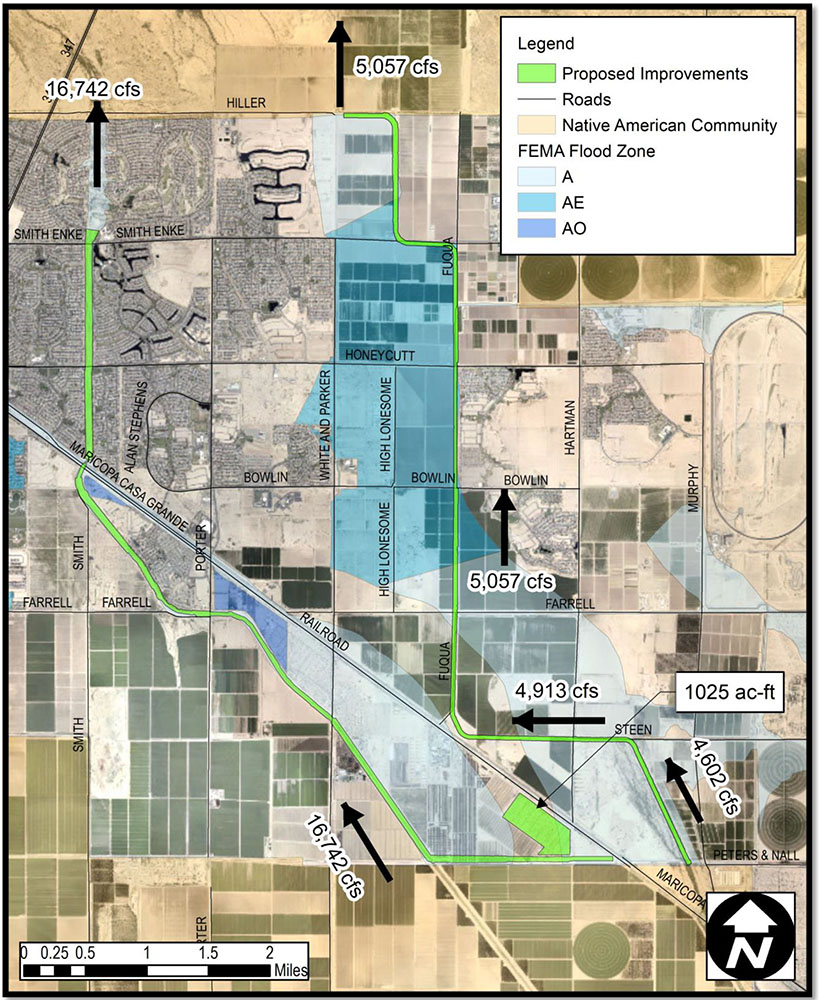

The City has big plans for commercial development around City Hall. That land is currently leased as agricultural acreage until it can be moved out of the floodplain designation. A primary portion of federally established flood zones lies between White and Parker Road on the west, Fuqua Road on the east, Farrell Road to the south and Smith-Enke Road to the north.

If all goes as planned, the project would draw flow from existing channels and accommodate so-called 100-year floodwaters in a new collective system. That would allow 11.2 square miles of property to be removed from the flood zone designation. Those acres could then be developed as the City thought it would be at the turn of the century.

Back then, developers had plans to channelize the Santa Cruz to solve the problems of being in the floodplain. But in 2014, the Federal Emergency Management Agency analyzed the Santa Cruz watershed. Its report changed everything.

“So, the City’s regional project had to take a step back after that data came out and reanalyze,” said Brad Hinton, a member of the Maricopa Flood Control District Board who has also worked for the City and for El Dorado Holdings.

He said the new study showed a different flood pattern that took in much more land than originally thought. The FEMA conclusion drew acres poised for development into the Special Flood Hazard Area map.

That had financial consequences for landowners, like mandatory flood insurance if they wanted to build on or improve their site or if they wanted to get a loan on property in the zone.

“Now it breaks to the west through existing development,” Hinton said. “The City has more skin in the game. Now, rather than just channelize the Northern Santa Cruz alignment, it involves improving the Santa Rosa channel as well.”

MARICOPA FLOODS

With the Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa and Vekol washes at hand, Maricopa is familiar with high water. The monsoon season in particular often sees roadways deep in runoff. It doesn’t even have to rain in Maricopa to bring stormwaters through the washes.

The Santa Cruz River has a northbound flow. It collects stormwaters from the southern mountains and sends them up through the washes in Maricopa and Hidden Valley and on to Gila River Indian Community.

Major floods over the decades have damaged property and stifled movement, even covered railroad tracks, playing a factor in the removal of the train route between Maricopa and Phoenix.

Maricopa historian Patricia Brock noted impactful floods in 1890, 1891 and 1905. Sweeping floods in 1946 and 1949 “caused great destruction and left them stranded for long periods of time.”

In 1983, a dam broke on the Santa Cruz River, sending a wall of water into Maricopa, again closing roads and inundating homes and businesses. Brock reported the height of the railroad tracks kept most of the water on the south side.

In 1990, it was a breach in the Smith Wash south of town that brought floodwaters into Maricopa again. Arizona felt the heavy rains that soaked the nation in 1993, resulting in more high water for Maricopa.

MITIGATION EFFORTS

The Maricopa Flood Control District and Pinal County Flood Control District maintain miles of channels. The Maricopa FCD is a special taxing district that has an elected board and is responsible for repairing damage and clearing vegetation that could prevent the flow of floodwaters.

It reviews plans by homeowners’ associations that may impact the Santa Cruz or Santa Rosa washes.

The Pinal County FCD has dozens of projects and studies ongoing, two of which directly impact Maricopa. A feasibility study with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has analyzed 80 stream miles of the Lower Santa Cruz River in search of a regional solution to flooding.

Though actually in District 3, the Russell Road Industrial Area project is attached to Maricopa. The project is studying drainage problems at Ak-Chin Regional Airport and the Saddleback Farms Subdivision.

The Pinal County and Maricopa entities disagree about the status and condition of the Santa Rosa levee, which is just south of the Union Pacific Railroad tracks. The City of Maricopa’s plan might make the “discrepancy of opinion” on the levee go away.

“The county doesn’t have proper records of the inspections when it was built,” Hinton said. “And then there have been some utility crossings that they think have cut into the integrity of the liner. They have maybe some valid reasons to raise some concerns, but I think we’ve mitigated it by doing our additional testing.”

Dan Frank, president of the Maricopa FCD board, said the City’s design potentially could remove the levee designation.

“That gets the county and FEMA, and its requirements to report to them and do certain maintenance things, kind of off our back,” Frank said.

NORTH SANTA CRUZ WASH REGIONAL FLOOD CONTROL PROJECT

“There is a large percentage of property within the current city limits that is within the floodplain,” Horst said. “We are working to try to mitigate that, in other words, to bring that property to where it can actually be developed.”

The recommended system for channelizing the Santa Cruz and Santa Rosa washes includes “interceptor/collection system, conveyance, detention and outlet systems.”

The Santa Cruz system would begin at Peters and Nall Road/Murphy Road and flow northwest to Steen Road, collecting from a South Side channel and traveling west along Steen before turning north at Fuqua Road. Flows would also be collected from Farrell Road to Fuqua and taken north toward the Gila River Indian Community boundary.

The recommended system for the Santa Rosa Wash “includes a proposed interceptor channel that will collect flow at the Peters and Nall Road alignment west of the UPRR,” according to the executive summary. An interceptor channel will tie into the existing Santa Rosa channel just west of Fuqua Road.

“I think what’s ingenious about this is we’re not having to build a lot of infrastructure,” Horst said. “We’re able to use the Santa Cruz Wash to carry a lot of this load. It’s already a natural channel and will save us a lot of money even though it seems like an expensive project.”

The rough estimate is $60 million.

“In essence, this will take approximately 11.2 square miles of property out of the floodplain. So, that’s a lot of acres,” he said. “And that acreage, once we bring it out of the floodplain, we will be able to ultimately develop it. If we develop it according to the current city pattern we’re following, that would be about $1.4 billion of new development opportunity.

“Of course, that won’t happen overnight, but it won’t happen at all if we don’t get it out of the floodplain.”

And even if the plan does not change the designation of the Santa Rosa levee, Hinton said the project “is going to help address and maybe do improvements to the levee to get the county and FEMA comfortable with it.”

On the other end, the City still must get GRIC on board, because all that re-directed flow won’t necessarily end up where they would like it. It is yet another project that must please local, county, state, federal and tribal entities to move forward.

The project 10 years in the making is only at the design level.

“Right now, the design concept report has been reviewed, and it has gone back into the county and the city for a second review and approval,” Hinton said. “After that, we’ll move forward with the 30% design, which is the CLOMR package.”

A Conditional Letter of Map Revision (CLOMR) is FEMA’s input on a project that will cause hydrologic or hydraulic changes. Maricopa is close to starting that process, but FEMA takes its time with these proposals.

“Projections are that we have a year-and-a-half process before we’re close to having FEMA’s approval,” Hinton said. “It’s a year-and-a-half to two-year construction process, too, though. It’s a big job.”

Optimistically, if FEMA and GRIC cooperate, it would be 18 months before any construction begins. GRIC is not an outlier. A GRIC engineer is part of the stakeholder meetings, and the sovereign nation knows it is an important player in a plan that could change Maricopa. Like FEMA, it has a long process in place and authorities to go through.

WHERE’S THE MONEY?

The elephant in the room is the funding.

In this case, having so many entities involved could become an advantage. All have different resources and connections. The city and the county are looking at various funding possibilities, and the flood control district sees options, too.

“That’s where the district could be involved,” Frank said. “We could look at the district’s ability to levy a tax or increase its levy.”

Is that likely?

“It’s hard to say,” Frank said.

That’s not a matter of the district doing a favor; it is affected by the City’s decisions. Maricopa FCD has easements through most of the channel. Maintenance agreements must be worked out, and that is a district specialty.

The City’s Capital Improvement Budget comes from taxes, fees and grants. With a COVID-caused slowdown expected, priorities could shift during the long process for approval. But Horst doesn’t mind spending $60 million to net $1 billion or more.

Hinton credits Horst with movement on the plan, calling him a “breath of fresh air in dealing with the City.”

“I think the project has moved in a positive direction,” he said.

This story appears in the July issue of InMaricopa.

![City gave new manager big low-interest home loan City Manager Ben Bitter speaks during a Chamber of Commerce event at Global Water Resources on April 11, 2024. Bitter discussed the current state of economic development in Maricopa, as well as hinting at lowering property tax rates again. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-041124-ben-bitter-chamber-property-taxes-web-218x150.jpg)

![3 things to know about the new city budget Vice Mayor Amber Liermann and Councilmember Eric Goettl review parts of the city's 2024 operational budget with Mayor Nancy Smith on April 24, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-042424-preliminary-budget-meeting-web-218x150.jpg)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)