It’s been nearly four years since the coronavirus pandemic shuttered the world. Every day, the memory becomes more distant; the grasps at normalcy more infrequent.

But the pandemic’s dystopian paradigm still lingers inside Maricopa classrooms, where graduation rates fell at a rate 10 times the state average and have yet to approach pre-pandemic numbers.

Faceless children swaddled in masks, video classes in empty rooms and social distancing may feel like relics of a not-so-distant past, but they were part of an ever-changing policy landscape that sowed dissension.

“I don’t think anybody was in favor of them, but every family had a different situation,” said Nate Wong, dean of academic services at A+ Charter Schools. “Some were directly impacted by COVID, others indirectly.”

When COVID ravaged the U.S. in March 2020 — Arizona was at one time the most infected state — schools followed county and state health officials in tracking cases and contacts.

“We were doing things like finding out who was sitting next to who on the bus and making sure we communicated to everyone on the bus and in the classroom,” said Tracey Pastor, assistant superintendent of administrative services at Maricopa Unified School District.

MUSD Communications Director Mishell Terry said the district had to keep up with constant health policy changes from the CDC.

“I think we were all kind of just learning together and there were mixed feelings,” she said.

Spray it forward

Glimpses of pandemic-era policy remain, the most visible of which are facemasks. In MUSD schools, children are required to wear masks at a parent’s request.

“Our governing board is very clear that there’s only one situation in which we ensure a student is wearing a mask and that would be if a parent has expressed they want their very young child or special needs child to wear a mask,” Pastor said.

She said this remains an option for parents when it comes to all respiratory illnesses transmitted through sneezing and coughing.

Similar policies apply at A+ Charter, where students wear masks voluntarily.

“We see a small percentage of kids who still voluntarily wear masks for whatever reason they feel necessary,” Wong said. “It’s a family decision and that’s what it always should be.”

Another practice that remains? More stringent cleaning practices in both public and charter schools.

“Keeping the kids safe when they came back was a priority,” Wong said. “There’s a more conscious effort to make sure things are clean. COVID-19 is a virus that will mutate, so we want to prevent that as much as possible.”

This meant a quick swipe of tables and chairs would no longer cut it. School leaders are making more conscious efforts post-pandemic to prevent the spread of not just COVID but also Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) and flu.

![Michelle Mills, a U.S. history and economics teacher at Maricopa High School, said her biggest challenge was not having faces to look at when she taught online. [Kyle Norby]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/EDUC-Seniors-COVID-Mills-600x450.jpg)

Michelle Mills, a U.S. history and economics teacher at Maricopa High School, said her biggest challenge was not having faces to look at when she taught online. [Kyle Norby]

“They’re all something we need to keep an eye on and remind kids about cleanliness and washing hands,” Pastor said. “On our end, we want to make sure that our buildings are clean and we’re doing what we can to keep sick kids away.”

This includes altering the previous protocol for quarantine after infection. Most schools still follow CDC guidelines to quarantine for 10 days.

“Those basic isolating guidelines are still in place,” Pastor said. “When students or staff test positive for COVID, they’re required to isolate… It’s just like with chickenpox, RSV or influenza. It’s best for them to isolate during that period of contagion.”

Schools continue to monitor COVID cases — though less frequently — to watch for concerning trends. But otherwise, school officials say they aren’t gunning for strict restrictions again.

“Unless the CDC or Pinal County’s health officials issue something, those other policies are not in place,” Wong said.

Mental toll

Floundering academic performance topped headlines in recent years with students by-and-large struggling to catch up to their grade level. But Wong said the pandemic has made nurturing students’ mental health and ability to understand and manage their emotions a priority.

“In recent years, there was already a decline in academic performance and social and emotional intelligence, particularly for junior high-age students,” Wong said. “COVID just exacerbated the problem.”

![Juan Garavito, who teaches 12th grade English at Maricopa High, said he found it challenging to get comfortable being in front of a camera. [Kyle Norby]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/EDUC-Seniors-COVID-Garavito-600x450.jpg)

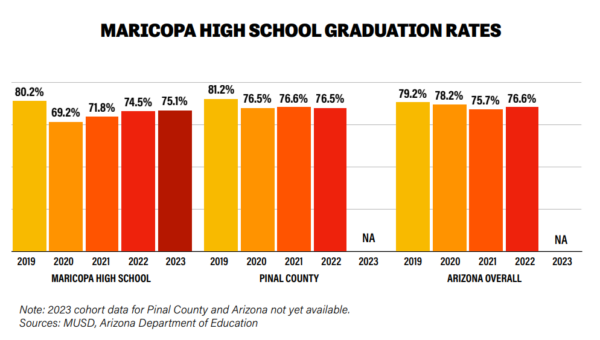

From 2019 to 2020, the graduation rate at Maricopa High School tanked from more than 80% to less than 70%. In the following years, graduation rates slowly climbed to around 75% — still lagging behind pre-pandemic numbers.

Maricopa fared much worse than most school districts in Pinal County, where graduation rates on average fell less than 5%; and in Arizona where graduation rates fell on average just 1%.

“We’ve seen an increase in students with anxiety or depression, so we’re doing our best to meet students’ social, emotional and mental health needs,” Pastor said.

MUSD administrators said this stemmed in part from children entering school for the first time in months and, for some, the first time ever. Others struggled to navigate both a changing world and large adjustments to family life.

“COVID’s impact on families and family dynamics also impacted our students,” Pastor said. “There are students who lost family members, whose family dynamics changed because someone lost a job. These life changes are impacting students.”

As a result, administrators found they needed to utilize more patience and compassion as kids returned to the classroom.

“It’s important to remember that we’re seeing kids as a snapshot right now,” Wong said. “They’re going to live in a different world, so we’ve been a lot more patient and exercise a lot more compassion when disciplining…We wanted them to feel comfortable in school again.”

A silver lining

Nearly four years on, with the third booster shot rolling out and an uptick in COVID cases around the country, it seems the disease will remain in schools’ peripheries indefinitely.

However, administrators say they’re trying to focus on the few silver linings that emerged from the pandemic.

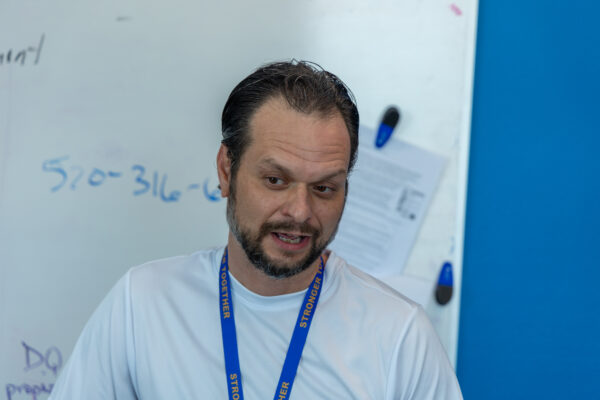

Nate Wong, dean of academic services at A+ Charter Schools, feels some students “were directly impacted by COVID, others indirectly.” [Brian Petersheim Jr.]

“During a recent parent meeting, I told parents about our plans to get kids caught up and to maximize the time they have in school and at home,” Wong said. “I think in some instances, COVID brought families closer together.”

For A+ Charter, the pandemic engendered a learning schedule never normalized before in the U.S.

“We want to make sure that when they’re home, they’re spending quality time with family, which is why we also moved to a four-day week,” Wong said.

The pandemic also forced schools to identify how to best utilize technology across the board. This included ensuring students can access their curriculum without setting foot on campus, using online learning platforms to distribute assignments and track grades.

In other cases, it meant new channels of communication with families.

“A lot of our families work outside of Maricopa, so they have options to meet with teachers online,” Terry said.

Wong said he’s hopeful this generation of students would make the best of the situation.

“There’s no desire to go back to online or masks or any of that,” he said. “But this generation is super compassionate toward each other, and they’re really good rolling together through everything. We just have to remind them that we can’t control too much of the outside world, but we can control how we work together and treat each other.”

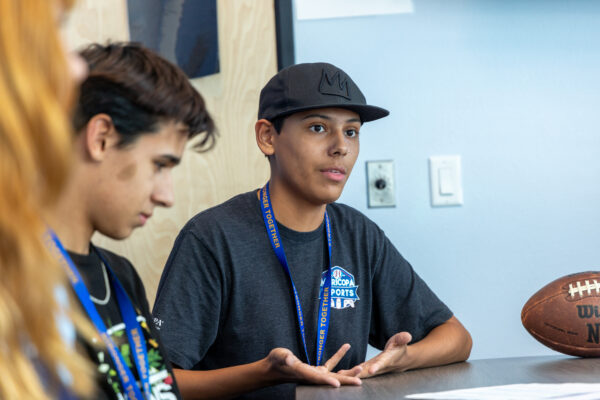

In their own words

Several students at A+ Charter School participated in a panel discussion with InMaricopa about their experiences during and after COVID. Students ranged in age from 8 to 14 when the pandemic began and struggled in various ways.

I was in eighth grade when COVID started. I was homeschooled my whole life and just registered to go to Maricopa High School. When COVID hit, that obviously didn’t happen. I was really bummed out and really hoping I could go to high school.

Since I was homeschooled before, not having a teacher telling me what to do or classmates to interact with was actually pretty normal for me. But I definitely slacked off a lot because I was home all the time and just thought I would catch up later.

Online was kind of isolating because you had to do everything on your own. You didn’t have a teacher there to talk to or classmates to ask to compare homework with. You were on your own, you had to figure it out for yourself. So, I definitely became more independent.

When schools reopened, it was my first time coming to school in-person, so COVID didn’t really affect me how it affected other kids. But I think the hardest thing transferring to in-person was that my online school didn’t have strict deadlines or penalties. Here, we actually got a penalty for late assignments.

If this happened again, I think we would know what to do and could be prepared to go through it again. But emotionally or psychologically, probably not. I don’t think any one of us could handle that period of isolation again. We were lucky it only lasted two years. We don’t know how long would last or if it would get worse than what COVID was.

I was in sixth grade when COVID first hit. I was actually excited about it because there was no school, it was like an extra-long break and an extra-long summer. But when fall started, I was like, ‘Wait, we’re not really going back?’ That’s when it started to get really hard, especially the whole online aspect of it.

I went to two schools during COVID, including an autism specialty school, and neither really handled online classes well. Communication was a big problem, and it was just hard trying to communicate with teachers.

The biggest issue was not the teachers but the students and disciplining students. Teachers couldn’t really do that. There was one kid who spammed the class with fart noises over and over again. She gave the kid multiple warnings, but she couldn’t really do anything because she’s not actually there and she couldn’t kick him out for long.

Coming back in person was awkward. You’re so used to not talking to people and then you couldn’t recognize people because of the masks. I didn’t really know what half of my friends actually looked like, so that was kind of weird when we didn’t wear masks anymore. It was like, who do I talk to? Who do I like? Who can I trust?

If something like COVID happens again, I feel like we’re more prepared for it. We already experienced it, so I don’t think it will really be a big thing for us. I don’t think it would impact us a lot.

Rafael Escalade, 16

I was in seventh grade. COVID definitely brought my studies back so that when I came back to school, I had to catch up on my learning.

It definitely taught me more about technology because I wasn’t really using it in school at the time. Once I had to do online school, it taught me how to use computers for education.

The most difficult thing for me was the work and the assignments. The teachers tried to teach us stuff but by the time you grasp the concept, we were so far behind. So, the teachers would have to go back and teach us again.

Bradley Barney, 11

I was in second grade and I was really excited because of the extra time in summer. But I was really nervous to start online school stuff because it’s something I never did before. It was really nerve-wracking.

When I started, my online school switched software every year I was there. It was hard to get used to, it was hard to communicate, and I didn’t learn as much. I noticed I wasn’t as engaged as I would be with in-person learning.

But I learned a lot about technology. It was a lot because I wasn’t really using computers in school at the time. So, I had to learn how to do all of that. I got very antisocial because of COVID, because I never talked to people a lot during that time. Whenever I would talk, I would stutter and just stop talking and start shaking.

I was excited to be out of school, but I didn’t really realize how long it would last.

I didn’t really learn a lot online, and I didn’t take in what I was supposed to be learning. We didn’t have Zoom calls, so we weren’t really being taught anything. It was more, “You guys work on this and figure it out.”

Eventually, it helped me be aware of the resources and how to research because I did that most of the time. I also got better with technology.

But I think COVID definitely set me back socially. Not being around a lot of people for a very long time just felt kind of awkward and uncomfortable. I felt very shy, but I eventually got over it. Last year was when school started to feel normal.

The November edition of InMaricopa Magazine is in Maricopa mailboxes and available online.

![A pair of students work on laptops while wearing masks in a classroom at A+ Charter School. [Courtesy of A+ Charter Schools] A pair of students work on laptops while wearing masks in a classroom at A+ Charter School. [Courtesy of A+ Charter Schools]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/a-plus-charter-students-covid-01.jpg)

![City gave new manager big low-interest home loan City Manager Ben Bitter speaks during a Chamber of Commerce event at Global Water Resources on April 11, 2024. Bitter discussed the current state of economic development in Maricopa, as well as hinting at lowering property tax rates again. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-041124-ben-bitter-chamber-property-taxes-web-218x150.jpg)

![3 things to know about the new city budget Vice Mayor Amber Liermann and Councilmember Eric Goettl review parts of the city's 2024 operational budget with Mayor Nancy Smith on April 24, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-042424-preliminary-budget-meeting-web-218x150.jpg)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)