It was the best of times; it was the worst of times.

For the city of Maricopa and the Ak-Chin Indian Community, Charles Dickens’ timeless prose hardly ever felt so fitting.

Like his allegory in A Tale of Two Cities, Maricopa and Ak-Chin have long labored in unison. But as in Dickens’ paradox, this altruistic exchange serves only to foreshadow an impending revolution.

The battleground? Where the John Wayne and Sonoran Desert Parkways converge like asphalt arteries in the heart of Maricopa.

Long slated for an innocent traffic light, this intersection now stands as a testament to bureaucratic folly. A decision made at the hands of city and tribal leaders more than half of Maricopa’s lifetime ago left behind only a dizzying maze of road cones, symbolizing the growing fracture between two communities that both publicly state otherwise.

Much like the intersection itself — where Ak-Chin police nearly staged a mass arrest of oblivious municipal workers — the road to riches took a sharp turn. A decade-long commitment washed away like the house of cards, like those hands dealt on felted tables just across the street, where the highway was meant to unfurl like a red carpet to the door of Harrah’s Ak-Chin Casino.

Every screech of the brakes in that sea of stop signs and traffic cones serves as a reminder of this tale of two cities, where a Berlinesque wall of neon blockades does more than divide land.

To the public’s beckoning ear, they’ll chant “the best of times.”

But a months-long scour of public records and conversations with city leaders show that, for the accord between these two thrones, it’s the worst of times indeed.

Kiss of Judas

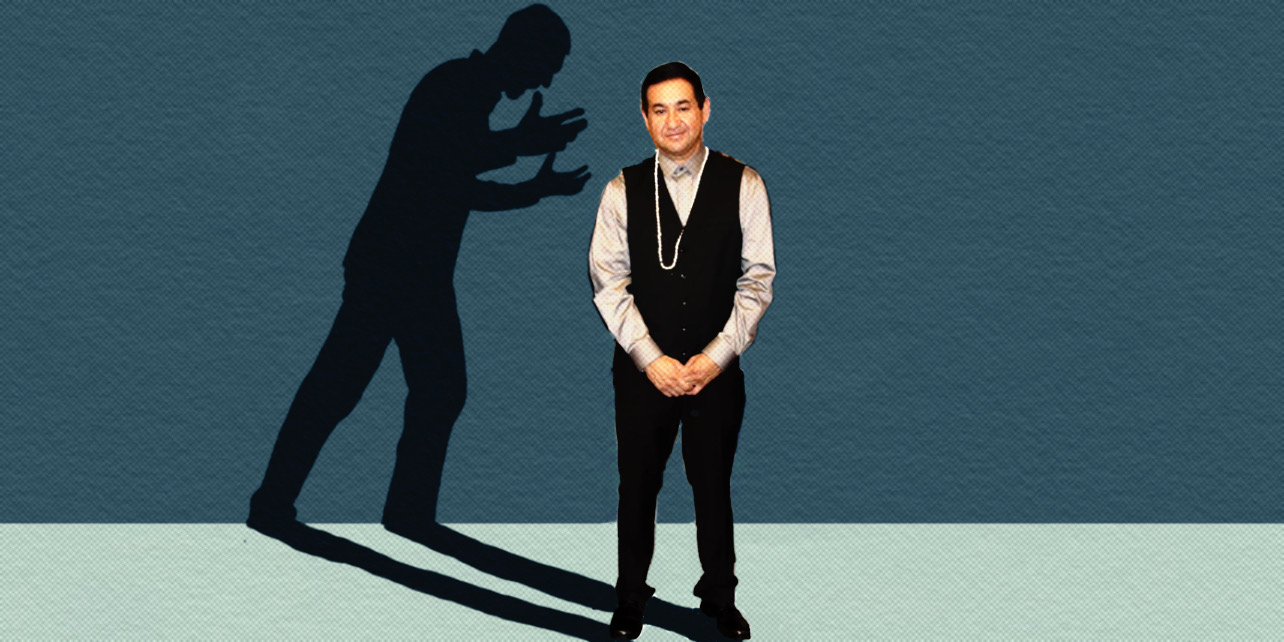

Ak-Chin Chairman Robert Miguel was in the eye of the hurricane that morning, but he grinned and made merry with city dignitaries over breakfast in a sunlit Maricopa conference room.

Less than a week elapsed since that scene straight from an old western movie played out near city limits, when Miguel “had to summon tribal law enforcement to maintain peace in such a volatile situation,” he wrote in a letter earlier that week.

And a volatile situation it was. But at that Sept. 14 breakfast, Miguel gushed about how Maricopa and Ak-Chin “have always been one family.”

His motto, he said that morning, is this: “What can we do to help? We’re willing to do what is needed to move forward in any way possible.”

But it was Ak-Chin that seemingly sought to sabotage the Sonoran Desert Parkway in the 11th hour, accusing Maricopa of trampling tribal sovereignty and flouting federal orders. All while the city tried to put the final bow on its gift to Ak-Chin — a $30 million highway leading nowhere but the casino, the community’s lifeblood.

Just last year, Miguel spoke at a groundbreaking ceremony about the Sonoran Desert Parkway, dubbing it “exciting” and “a great opportunity” as he motioned his hand to the casino complex and promised the highway would go “right directly to that beautiful place over there.”

The Sonoran Desert Parkway finally opened Oct. 11. It’s impossible to access the casino from that road.

For the city, it wasn’t for lack of trying.

All-time low

Miguel penned a letter to Maricopa Mayor Nancy Smith that same week lobbing insults at city leaders and saying the time “marked a low point for the relationship between the community and the city.”

Who at that breakfast table would have predicted such words amid platitudes of family unity?

If she has the key, she’s yet to unlock anything.

A month earlier, Smith dared Ak-Chin to play by the rules. She gave an ultimatum: Allow the city to build the traffic signal as originally planned or get axed from the project. And she followed through.

Diplomacy aside, Smith agreed battling over the traffic signal was the biggest obstacle in more than a decade of work on the tailor-made thoroughfare, which one day will link John Wayne Parkway and Interstate 10.

City Manager Rick Horst and Vice Mayor Rich Vitiello were among others to name that dispute the project’s largest hindrance — it cost taxpayers thousands of dollars a day as Ak-Chin forced workers to wait idly by.

And it all comes down to 50 feet of road at that crucial intersection — a sliver of land Ak-Chin gated, padlocked and barbed-wired when it heard Maricopa would place the final piece of the parkway puzzle, city officials say.

The U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs did not grant Maricopa the legal right-of-way necessary to connect traffic signals there, according to Ak-Chin.

Public records tell a much different story.

You can’t park(way) there!

The Arizona Department of Transportation has operated that splinter of road as a public highway since it was built in 1990. That year, Pinal County purchased the rights to operate on Ak-Chin land from — who else — the BIA.

The city holds permits to work there from both ADOT and Pinal County, according to government documents from a hundred-page file the city supplied to InMaricopa.

That didn’t stop the BIA from throwing its weight behind Ak-Chin’s gripes, issuing three cease and desist letters in May, August and September. The letters are just that — requests — but Ak-Chin wrongly asserts the city “violated federal law” and “violated a federal order,” although no such order exists.

Ak-Chin believes federal law stands in the way. Its hands are tied.

Ak-Chin Community Council said as much when it told InMaricopa last month, “It is important that the project comply with federal law. Neither tribal nor municipal officials have authority to waive or disregard federal law, including the need to secure proper right-of-way before completing work on tribal land.”

But wait — not so fast.

After the mayor said any future plans to connect a traffic signal at the John Wayne and Sonoran Desert Parkways “would be at the sole expense of Ak-Chin,” the community suddenly offered a new way to sidestep that federal law — like magic.

The Ak-Chin council refused to answer questions from InMaricopa about this unexpected loophole, which would require the city to simply fill out a form.

Ak-Chin spokesperson Matthew Benson categorized the form as “a workaround.” However, it demands details that don’t seem to fit the spirit of Miguel’s commitment to do “anything possible” to complete the project as planned.

Presented as a compromise, city leaders said the workaround was more of a slap in the face.

“We had to fill out every worker, their license plates, their driver’s licenses, their VIN numbers,” Vitiello, the vice mayor, told InMaricopa. “It’s impossible, as everybody knows.”

As such, Ak-Chin’s entertainment complex won’t be accessible via the Sonoran Desert Parkway. And that’s on a “permanent” basis, according to city records.

Yet, Ak-Chin told InMaricopa days after the highway opened it was still “hopeful” about negotiating an agreement with the city. And Benson told InMaricopa Oct. 18 “every indication says they’re going to finish the work.”

BIA has yet to return a Freedom of Information Act Request from August for its conversation with Ak-Chin about the issue. ADOT Director Jennifer Toth declined to comment.

‘Power trip’

“Like a good neighbor, Maricopa is there,” Vitiello sang to the tune of the iconic State Farm jingle as a white shuttle bus bumped along the Sonoran Desert Parkway Oct. 4.

Eight of the city’s top brass, Arizona state Rep. Teresa Martinez and InMaricopa journalists made the first official drive down the parkway that balmy Wednesday evening.

Vitiello laughed, then became pensive.

“There’s no apparent reason for any of this,” he said. “I mean, they had cops out here ready to arrest our people.”

For Vitiello and others in city leadership, it’s a mystery why Ak-Chin would sabotage a mere traffic light — one that wouldn’t cost it a penny and would usher patrons to its lone center of commerce.

How will it justify that decision to its community members? The council wasn’t willing to answer that question.

“They’ll just keep blaming us,” Vitiello offered. “That’s all they’re going to do.”

Checkmate

This isn’t the first time Ak-Chin blocked the city’s development efforts.

Since 2019, Ak-Chin has been impeding an agreement between the city, Apex Motor Club and Global Water to extend a water main down State Route 238 and allow for expansion to the west.

The community gobbled up the golf course and the airport. It eyed other properties both east and west that would complicate the city’s ability to annex further into its extensive planning area, which yawns all the way to Interstate 8.

With its unincorporated square parcels slowly captured like pawns to a queen, the Maricopa map resembles a chess board, says Horst, the city manager.

What does that make all of this? A chess game.

“I can only speculate. But it’s all part of their power trip,” Vitiello said. “It gives them the power. That’s it.”

Ak-Chin Community Council refused to respond to the vice mayor’s comments.

‘People will be hurt’

Turn right from Porter Road onto the Sonoran Desert Parkway and you’ll cross four different speed limits before you reach that infamous juncture with John Wayne.

You’ll face the casino head-on, but with no way to access it.

In lieu of the traffic signal planned at that intersection since 2011, it’s a meander of florid road cones and barriers funneling drivers away from Ak-Chin land from all sides of a four-way stop.

Smith told InMaricopa Oct. 10 she had “no concern” about safety at the intersection, citing ADOT engineers’ approval of the permanent traffic condition. But in a Sept. 8 letter to Ak-Chin, she wrote Ak-Chin’s noncompliance “poses a serious safety concern.”

Maricopa drivers are certainly concerned.

“It is dangerous and people will be hurt,” Lee Morano said.

Resident Ken Menez said, “The way it is right now, it won’t be long before the first accident.”

Another resident, Brian French, offered, “This road shouldn’t even be open until this is fixed. Someone will get hurt or killed.”

These fears stretch to the state capitol.

Martinez, the GOP lawmaker representing Maricopa, remembers seeing her father’s face for the last time before he died needlessly in a crash on the way to San Manuel. For her, it’s personal on multiple levels.

“I don’t want there to be accidents that prompt the safety light to be up after all,” Martinez told InMaricopa. “That is very concerning as a safety issue and I fear about what could happen.

“I don’t want us to have a fatality there because we didn’t have a stupid traffic light.”

Martinez said an accident there could open any party to a lawsuit. Ak-Chin isn’t immune.

She spoke highly of both Smith and Miguel, calling the dispute a “miscommunication” and pledging her support to help settle tempers and achieve a compromise down the road. But for now, she’s scared.

With good reason.

Like city leaders, she struggles to understand Ak-Chin’s opposition to the traffic light it not only agreed to but asked for.

“The Sonoran Desert Parkway bypasses a lot of the Ak-Chin land,” she said. “It’s not always positive and polite. But it is what it is and it ain’t what it ain’t.”

Broken promises

Three hours.

That’s how long it took then-Maricopa Mayor Christian Price to drive from Maricopa to Flagstaff on May 9, 2014.

Price made a habit of driving all over the state to attend ADOT board meetings. But this one was special, for two reasons.

His mind was occupied with thoughts of a 500-foot-long overpass above the train tracks at the John Wayne Parkway-Honeycutt Road intersection. ADOT had just added the project to its five-year plan.

And at this meeting, Ak-Chin’s then-chairman and vice chairman, Louis Manuel and William J. Antone, were tagging along.

During a public address of state leaders, Ak-Chin pledged nearly $15 million toward that overpass, according to public records supplied by ADOT.

That’s a number that “was said many, many times,” Price recalled. Public records show Ak-Chin promised somewhere between $10 million and $15 million for the $55 million project to myriad state leaders over the years.

In 2019, the overpass debuted in one of the most pivotal moments in city history. Ak-Chin never gave a dime.

Benson, the community’s spokesperson, said he wasn’t aware of any promises to fund the overpass.

“Ak-Chin is saving face right now because nobody at the moment has any liability,” Price told InMaricopa. “When Chairman Miguel won, those promises that were made, they fell by the wayside.”

Price likened the political atmosphere on the Ak-Chin Community to the Russo-Ukraine War. Some people on the street may support it, but there are those in Washington who think it’s all too expensive.

“That’s the way they do business —things can be retracted until that money is ready to go,” he explained. “The politics changed. The view internally changed. There was never anything written, never anything proved.”

Nothing, perhaps, aside from ADOT records documenting promised funds. But it was never anything binding, Benson was quick to point out.

Just a tease. A flashy, years-long tease.

For Miguel, who is term-limited with nothing to lose, it’s already a distant memory.

“For decades, the Ak-Chin Indian Community has been a good neighbor to the city of Maricopa,” Miguel asserted at that September breakfast. “We’re never asking for anything back.”

Is either statement true? Not according to Vitiello.

“After that ordeal, they asked us for our lights and signs,” he said. “And Nancy [Smith] gave them the signs anyway.”

A tale of two cities

Four years ago, Price and Miguel stood shoulder-to-shoulder, waving at the crowd from the top of float at the Maricopa Veterans Day Parade.

That memory feels far more distant today than it did just two months ago.

Smith insists she has taken up the mantle for Price in cultivating that “one family” relationship Miguel says he’s so proud of.

“The relationship between the city and Ak-Chin is something that every mayor and council has improved since the city was incorporated,” she told InMaricopa.

But Miguel says this is “a low point for the relationship between the community and the city.”

As in A Tale of Two Cities, it’s a paradox with no clear solution.

It’s the best of times, it’s the worst of times, after all.

A road to nowhere

Since the Sonoran Desert Parkway opened for traffic last month, many Maricopa residents have labeled it “a road to nowhere.”

Unless you live in Hidden Valley and frequently shop at Walmart, it’s not hard to see why 12 years of anticipation felt a little anticlimactic. After all, an informal poll of InMaricopa readers last month found that, for more than 4 in 5 residents, the highway won’t shorten any usual commutes.

But Arizona state Rep. Teresa Martinez, the Republican representing Maricopa, says the purpose-made parkway wasn’t built for today — it was built for tomorrow.

“We don’t have enough traffic for that road today,” she conceded. “But we’re going to have it someday.”

Martinez, who is in her first full term, sponsored a bill that secured more than $9 million for the 15-mile, four-lane freeway linking John Wayne Parkway and Interstate 10.

That money could have gone toward any other road — State Route 347, State Route 238, Maricopa-Casa Grande Highway — or other troubled roads in her district like Thornton Road and Pinal Avenue.

“As a legislator, I have to make improvements to existing roads and make them safe,” Martinez said.

That’s why she and state Sen. T.J. Shope secured tens of millions of dollars for relief at Cement Plant Road and to widen SR 347.

“When the 347 came to existence, it was short-sighted,” Martinez said. “Everybody knows the 347 is inadequate. It wasn’t planned well enough.”

The Sonoran Desert Parkway will eventually allow drivers to totally bypass the 347 during commutes to Phoenix.

As the corridor between Phoenix and Tucson continues its rapid growth, the Sonoran Desert Parkway serves to prevent such short-sightedness in the future.

“If we take that money and widen Maricopa-Casa Grande Highway, it would not be sufficient,” Martinez said. “The Sonoran Desert Parkway lays a foundation down for a future. We have to create a vision of an exciting parkway so that we can expand for growth.”

Just 20 years after incorporation, Maricopa has already eclipsed Casa Grande — a century-old city — to become the most populous municipality in Pinal County.

Maricopa is “a young, beautiful 20-year-old who’s ready to hit the town,” Martinez jokes. But that’s what makes anticipatory projects like this one so important.

Before too long, new homes and businesses will line the parkway on either side. A restaurant row concept is planned for the city center along with new parks and other forward-facing amenities.

“We have to start connecting the future growth that’s coming,” Martinez offered. “It’s either one day, or day one.”

To the large majority of Maricopans who said the parkway’s first phase won’t save them any minutes behind the wheel, Martinez says, “I understand your feelings. But on the other hand, when do we start preparing for the future?”

When is the future? Five years, she says.

In 2028, growth in Pinal County won’t just use the Sonoran Desert Parkway — it will demand the Sonoran Desert Parkway.

“I have to prepare for growth,” Martinez said. “Do we need it today? No. But we will definitely need it tomorrow.”

The November edition of InMaricopa Magazine is in Maricopa mailboxes and available online.

![City gave new manager big low-interest home loan City Manager Ben Bitter speaks during a Chamber of Commerce event at Global Water Resources on April 11, 2024. Bitter discussed the current state of economic development in Maricopa, as well as hinting at lowering property tax rates again. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-041124-ben-bitter-chamber-property-taxes-web-218x150.jpg)

![3 things to know about the new city budget Vice Mayor Amber Liermann and Councilmember Eric Goettl review parts of the city's 2024 operational budget with Mayor Nancy Smith on April 24, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-042424-preliminary-budget-meeting-web-218x150.jpg)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)

But the only people who suffer for this is you and me. The residents suffer for the politicians power struggles.