Some shy musicians may play the guitar or the piccolo in private. But it is practically impossible to be a private bagpipe player.

That is why Terry Oldfield and Dave Mundy are quite certain they are the only bagpipers in Maricopa.

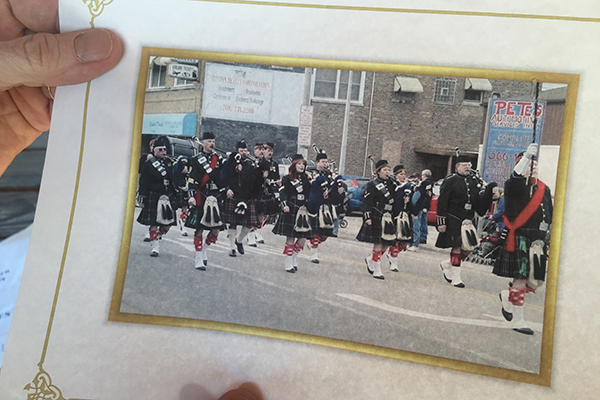

Their uniqueness is a change from their pre-retirement days when they performed with entire bands of pipers – Oldfield in Chicago and Mundy in Denver.

These days they turn heads whenever they show up at a Maricopa event, kilted, with drones set and chanter ready to go. The piercing sound of the pipes draws varied reactions, but Oldfield and Mundy have always had a strong affinity for the music.

“It’s an emotional response,” Oldfield said. “It stirs you.”

After a pause, he said, “It’s an instrument of war.”

In fact, Mundy is drawn to the deep history of the instrument in military action.

“It’s almost like you’re marching with the men in World War I, World War II or Korea,” Mundy said.

Oldfield, a 23-year veteran of the U.S. Navy and the finance officer and chaplain for American Legion Post 133, is often seen and heard at veteran events in Maricopa. Mundy, who is not a veteran, is asked to play at military and nonmilitary gatherings as well.

Over the years, they have both done their share of Celtic celebrations, from January’s traditional Robert Burns Suppers, to the “Irish times” events of March to a variety of highland games and Caledonian gatherings across the country. (A Burns Supper honors the Scottish bard’s birthday just weeks after so many closed out the old year by singing Burns’ enduring “Auld Lang Syne.”)

In those settings, anyone in a kilt fits right in. Frequently, they are required. Oldfield wears a MacMillan tartan. Mundy wears the Colorado state tartan.

They are also invited to play not-necessarily-Celtic events where a kilt draws stares – weddings, funerals, military and first-responder events, golf tournaments, church services, flag-raisings and, in Oldfield’s case, at least one bachelorette party.

They share war stories from piping competitions, pub crawls and parades. (“Horses don’t like bagpipes,” Mundy said.) Oldfield spoke of one parade in weather so miserable there were no attendees. The band had enough, took a right turn and marched into a pub.

Already playing guitar, banjo and mandolin, Oldfield took up the bagpipes in his 40s. His wife Bonnie encouraged him to pursue lessons, something he had always wanted to do. Through an acquaintance he met bagpipe teacher Scott McCawley, who was studying to be a priest at the time.

“It’s a process,” Oldfield said. “It was more than a year before I could play a tune on the bagpipes.”

Mundy’s story is similar. The son of an English father who became a naturalized American and a Canadian mother who did not, Mundy had a lot of exposure to pipe bands in Ottawa. When he was in his early 50s and a psychologist for drug and alcohol addiction, his significant other Judy found top-grade bagpiper Ben Holmes in the phone book and convinced Mundy to give it a try.

That training led to performances just about everywhere from a Denver Broncos game to a roller derby.

For both Oldfield and Mundy, the most unforgettable experience piping has brought them travel to Edinburgh, Scotland, with thousands of massed pipes and drums playing in thunderous unity.

“That’s a whole different ballgame,” Mundy said.

One of Mundy’s most memorable performances was a solo “concert” for an ill veteran of World War II who wanted to hear the pipes again before he died. Mundy played 45 minutes of Scottish airs.

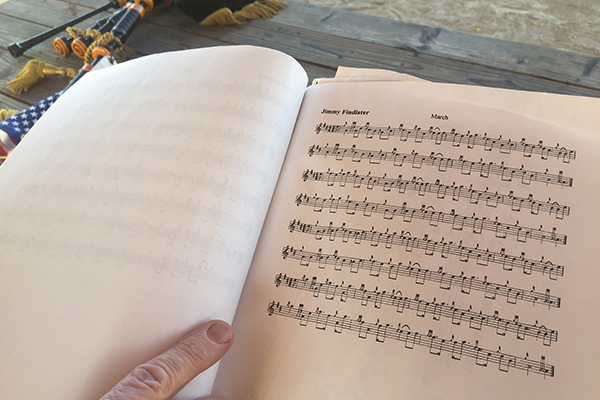

Oldfield cautions prospective bagpipers to be patient and expect many months of lessons. Bagpipes have only nine notes, which calls for adapting and substituting in some music. Besides standards that are among his favorites like “Highland Cathedral” and “Amazing Grace” he will play an assortment of popular and patriotic tunes when appropriate.

Mundy has a fondness for “The Dark Isle” and what requesters were calling “that other Scottish song” until he figured out they were asking for “Scotland the Brave.”

While the first bagpipe instrument may have first appeared in the Middle East more than 2,000 years ago, Scotland perfected it and made it a symbol of national pride and even insurgence. As the Scots proverb goes, “Twelve highlanders and a bagpipe make a rebellion.”

Britain’s Highland regiments, dating to the 18th century, often brought bagpipers into war. They also often wore kilts, leading the Germans in WWI to call them “Ladies from Hell.”

WWI journalist Michael MacDonagh described the response to bagpipe music as “impressions, moods, feelings inherited from a wild untamed ancestry.”

American writer Loretta Chase described it as the “sound of death and torture and the agonies of a burning hell.”

Whatever it is, it is not subtle.

“There’s one level of sound. There’s no soft,” Mundy said.

This story appears in the January issue of InMaricopa.

![3 things to know about the new city budget Vice Mayor Amber Liermann and Councilmember Eric Goettl review parts of the city's 2024 operational budget with Mayor Nancy Smith on April 24, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-042424-preliminary-budget-meeting-web-218x150.jpg)

![MHS G.O.A.T. a ‘rookie sleeper’ in NFL draft Arizona Wildcats wide receiver Jacob Cowing speaks to the press after a practice Aug. 11, 2023. [Bryan Mordt]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/cowing-overlay-3-218x150.png)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)

![3 things to know about the new city budget Vice Mayor Amber Liermann and Councilmember Eric Goettl review parts of the city's 2024 operational budget with Mayor Nancy Smith on April 24, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-042424-preliminary-budget-meeting-web-100x70.jpg)