To steal valor is to adorn oneself in borrowed laurels of courage.

To steal valor is to adorn oneself in borrowed laurels of courage.

It’s the product of either malice, cowardice or vanity, and generally misses its aim in each of these aspects. Because sooner or later, the carefully placed blocks of deception topple under the gravity of truth.

Some weave grand lies and exit dramatically. Then there’s Stanley Wayne Wineberg Jr., who spun a slow-burning tale of wartime heroism that spans decades and a great distance.

But it’s here in Maricopa where the curtain may fall on his exploits. It was in this city where the seemingly innocent U.S. Army vet became the focus of a state criminal investigation in September.

He scammed a state agency and got away with it, forcing a change to the department’s legal policy last month. But that’s the mere tip of the iceberg.

Cue the unraveling.

Vanity plates

Wineberg, by all accounts, seemed like any other Maricopa resident.

He’d drive home from his job as a cable guy, park his truck in the driveway of his Glennwilde Groves home and greet his newlywed wife at the door.

The setting sun would throw a beam of light against his polished Purple Heart license plates as his wife closed the front door on another picturesque day.

She didn’t know about the half-dozen wives who came before her. She didn’t know he left them all in financial ruin. She definitely didn’t know she’d be next.

What else didn’t she know? Plenty — like his criminal record, bankruptcy, mounting back child support, tax fraud and IRS fines. And she hadn’t yet figured out those Purple Heart license plates were obtained fraudulently.

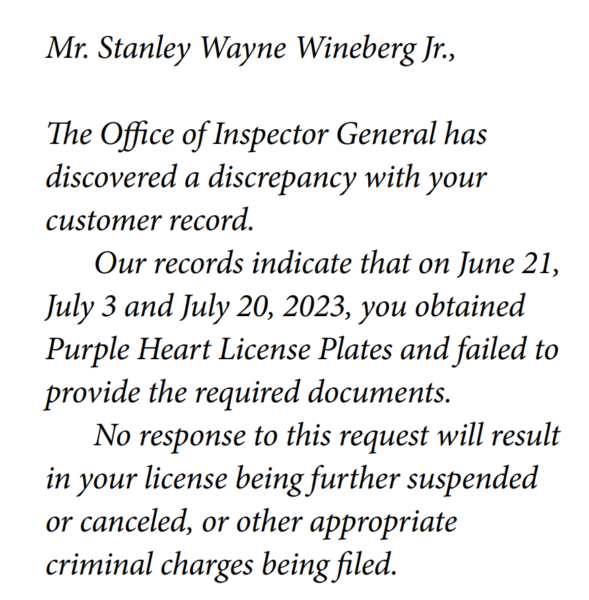

Not until that letter from the Arizona Office of Inspector General came in the mail Sept. 11.

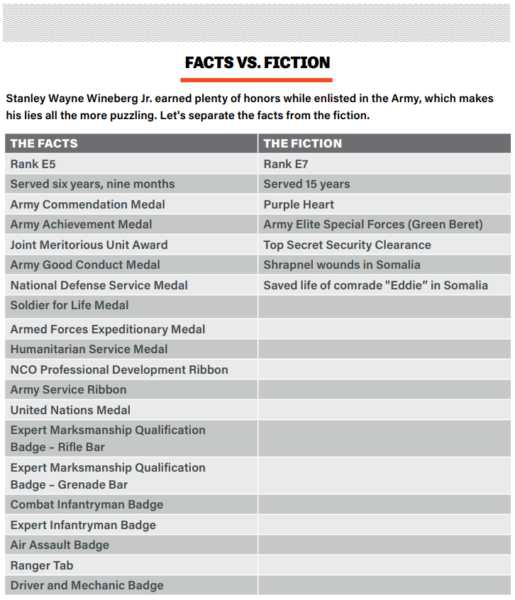

Wineberg fronted as a Sergeant First Class in the Army with 15 years of service, a Green Beret in the Elite Special Forces with Top Secret Security Clearance. He earned his Purple Heart, telling anyone who would listen, when he suffered shrapnel wounds, saving his comrade “Eddie” in Somalia.

Indeed, Wineberg is an Army veteran who was honorably discharged, earning 18 medals and badges along the way. And yet no detail in his story — not a single one — is true.

He served fewer than seven years, according to military service records obtained from the National Personnel Records Center through a Freedom of Information Act request.

Wineberg’s highest rank was E5, two notches below what he claims. The records don’t mention Somalia. Although his awards suggest he saw combat, he was also a driver and mechanic.

He never received a Purple Heart, the National Archives confirmed. He’s not credited with saving anyone’s life. He had standard security clearance, and he was never in the Special Forces.

Yet his Purple Heart vanity plates read “SF RNGR” — Special Forces Ranger.

Gone fishing

Earl Fisher isn’t just a detective at the Office of Inspector General in Phoenix. He’s also a proud veteran who served in the Vietnam War as a medical combat corpsman.

For him, investigating stolen valor is personal. So, when the state opened its investigation into Wineberg, Fisher was the man for the job.

“He’s a vet, but he’s not happy with what he has,” the detective told InMaricopa. “He wants more.”

According to Fisher, Wineberg abused a loophole in the system. Had he gone into a Motor Vehicle Division office to request his plates, he would have been denied. But he used the MVD Now website to order them, which at the time would send the tags by mail and allow the driver to supply his DD Form 214 — military discharge paperwork — after the fact.

Under Arizona law, he needed to prove he received a Purple Heart to obtain those plates.

“Because of the glitch in the system, I couldn’t prosecute him,” Fisher said. “I brought it to MVD’s attention, so they’re fixing that flaw.”

Instead, Fisher sent the letter demanding Wineberg turn in the plates or face criminal charges. The detective didn’t confirm whether he surrendered the plates and neighbors reported seeing them months later.

When he received the letter, Wineberg called the inspector general’s office.

“He was very distraught when he called me, probably because he thought I was going to arrest him,” Fisher recalled. “He said, ‘I made a mistake, I was in a bad place.’”

For Fisher, Wineberg’s Somalia story reeked of falsehood. “I don’t know how that story can be true,” he said. As soon as a soldier is wounded, his unit would recommend the Purple Heart and it would be awarded immediately upon treatment.

Wineberg never supplied a DD Form 214.

“If he provided any of those documents, they would have been forged,” Fisher said. “That’s where we’d get him. On forgery charges, and maybe tampering with public records.”

Fisher said he believes Wineberg is guilty of stolen valor, a federal crime that carries a one-year prison sentence. It’s a separate felony charge in Arizona that could mean more than four years in prison.

It’s unclear if a forged DD Form 214 exists for Wineberg. He joined a Combat Veterans Motorcycle Association chapter in Denver, where he wore a Purple Heart medal on his jacket. The nonprofit veterans’ charity requires discharge papers from its members.

“We cannot meet your request without authorization from the former member,” the chapter said in response to inquiries about the matter.

Wineberg did not respond to requests for comment from InMaricopa.

Medal detector

Bryan Masche was running a Republican bid for governor when he met Wineberg at a speaking engagement in Maricopa last year. The eight-year Air Force veteran still remembers touching Wineberg’s fake Purple Heart medal and thanking him for his service.

It’s a memory that now disgusts him.

“There’s nothing more disrespectful, hurtful, insensitive and plain disgusting in my book than stolen valor. It speaks to a deep-seated psychological personality disorder,” said Masche, who studied psychiatry in college.

“It’s hurtful. It’s sleazy. It speaks to a number of different psychological conditions that someone is so hard up for attention, they have to go out of their way to make up lies about who they are.”

Masche worked closely with the Army on deployment. He’s active in veterans’ groups and understands their psychology.

It made him uneasy when Wineberg didn’t ask about his military experience, but rather touted his own heroic stories.

“People who have seen really bad stuff, they just don’t talk about it,” Masche told InMaricopa. “When Stan talked about Somalia, all these pieces were starting to come together. I was figuring it out in my mind.”

Masche once called out a phony war hero in Scottsdale just minutes after meeting him. This one took him a little longer than he liked to admit, but sooner or later, he figured it out.

“Something in my stomach just didn’t sit right in that situation, but I couldn’t quite figure it out,” Masche said.

Then, he started replaying their conversations in his head. Something clicked.

“Here I am thinking Stan was somebody who was involved in combat, in a disaster in Somalia,” he said. “In actuality, he wasn’t asking me about my service because he knew I would, in a short amount of time, realize this guy was full of sh*t.”

Warriors wanted

Warriors wanted

Stolen valor — the act of making false claims about military service — is a term coined by Vietnam veteran B.G. Burkett in his titular 1998 book. He busted so many people exaggerating and inventing their service records that he dubbed it “a national phenomenon, a weird ripple in the American psyche.”

At that time, it was a crime to merely display a false military medal as Wineberg did — albeit under the same statute that made it illegal to impersonate a 4-H member. After an Arizona man falsely told newspapers he was a decorated war hero who captured Saddam Hussein, Congress passed the Stolen Valor Act of 2005 making it a crime to wear unearned military medals.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled the law a violation of the First Amendment in 2012, prompting the Stolen Valor Act of 2013, which made it a crime to profit from false military accomplishments.

“I think it was a bad call on the part of the Supreme Court,” American Military News journalist and stolen valor researcher Cheryl Hinneburg told InMaricopa. “Those who are guilty of stolen valor should be prosecuted to the full extent of the law. It is a slap in the face to our military and veterans.”

In 2019, Congress upped the federal prison sentence from six months to 12 months for violating the stolen valor law. But just one year later, investigators at the National Archives reported stolen valor cases were on the rise.

After InMaricopa exposed another fake war hero in July, the magazine asked its readers if the penalties for stolen valor fit the crime.

About 3,000 people answered the poll, with more than 85% saying the penalties are not strict enough. One in 10 respondents said the penalties were adequate while just 1 in 100 said they were too strict.

After learning his story, Hinneburg didn’t feel qualified to answer if Wineberg violated stolen valor laws.

“It is a federal crime if he used ribbons or medals to obtain something of value,” says Chuck Pardue, a military law attorney in Evans, Ga.

And obtain something of value he did.

Veterans affairs

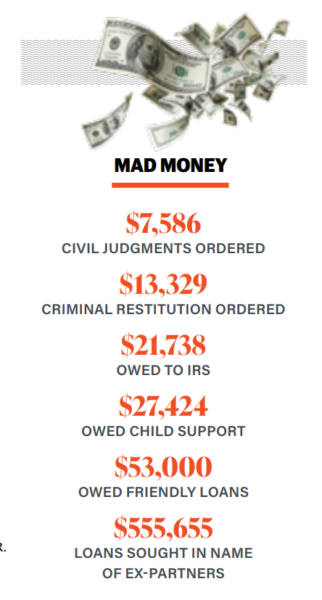

Susan Buonsante was married to Wineberg less than a year when she found out about his stolen valor. Not before he took her for $70,000, she said.

“I had no idea the man I married was a con artist and a serial predator of women,” she told InMaricopa. “He fabricated nearly every detail of his life story.”

Buonsante spent more than $55,000 on a parcel of land in Hidden Valley under the auspice her new husband would obtain a VA-backed Veterans Home Loan to build a house there.

According to a divorce decree in Pinal County Superior Court, Buonsante was awarded the land “due to Wineberg engaging in fraud.”

Wineberg has been married at least six times and has at least six children, none of whom he supports, according to government records.

He married one woman four days after divorcing another — and owes at least $27,424 in back child support, according to official records from the Colorado Office of Economic Security supplied to InMaricopa by two women.

Caren Fluharty, the mother of one of his daughters, told InMaricopa he tried to dodge child support by claiming his sperm was genetically modified to only produce male children. He still owes her more than $8,000 in child support although his daughter is 21 years old.

“Within a week, he moved in with me,” Fluharty said. “He rented a home in my name that was four times what I could afford. When I told him I was pregnant, he packed his sh*t and left, and I got evicted.”

Fluharty estimates Wineberg took her for $19,655.

They were never married, although court records show an El Paso County, Colo., judge issued a permanent restraining order against Wineberg in 2001.

Another ex-girlfriend, Tina White, estimates she lost north of $71,000.

White said Wineberg took out three vehicle loans in her name: $50,000 for a brand-new Chevy Silverado and $21,000 for two brand-new Honda dirt bikes. He convinced her to borrow $400,000 for a home loan in his name but disappeared the week of closing, she said.

“He put me in a very bad financial situation,” White told InMaricopa through tears. “He is very abusive towards women. He promised to pay back the money he owed me, but he never did.”

Crime doesn’t pay

Crime doesn’t pay

It’s difficult to pinpoint the genesis of Wineberg’s financial woes.

Judges in Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico ordered him to pay restitution in seven civil lawsuits he lost between 1994 and 2016.

He’s been evicted at least four times in Colorado and metro Phoenix.

In 1998, on the same day he was discharged from the Army, Wineberg was charged with theft, computer crimes and possessing a forged instrument.

A Denver District Court judge in Denver ordered him to pay his victims $13,329 in restitution and court fees after he pleaded guilty to the latter charge in a plea bargain and was sentenced to fines and probation. He violated his probation in 2004, court records show. A public records request for case documents did not reveal specifics about his crimes.

IRS records obtained by InMaricopa show Wineberg didn’t file taxes for nearly a decade, racking up $21,738 in penalties as of September last year.

In 2019, he finally filed for bankruptcy.

But his financial misdeeds continued, according to his former employer, Chris Hofmann.

In 2020 and 2021, Wineberg filed W-2 Forms with the IRS naming Sioux Falls, S.D.-based TAK Communications as his employer.

“He never worked at TAK,” said Hofmann. “Everything he did with us was 1099 [contract] work.”

Hofmann supplied Wineberg’s 1099 Forms and called the W-2 Forms “fake.” He noted the employer identification number didn’t match the company and that the company does not issue W-2 Forms.

Wineberg used those fishy W-2 Forms to both file taxes and apply for mortgage loans.

According to a letter from the IRS to Wineberg last year, the IRS “has no record of a processed tax return for 2020.”

Hofmann, who hired Wineberg based on his resume — which was supplied to InMaricopa and boasts the bogus Purple Heart medal — sympathetically loaned him $3,000.

Weinberg never paid back the loan, telling Hofmann he was tending to his deceased father’s affairs in Florida.

His father is alive and healthy today.

Fortunate son

Wineberg since moved to Apache Junction. His days in Maricopa have come to a somber close.

What of his days of stolen valor?

The fabrications about his military service date back decades, according to those close to him.

Some habits are hard to break. But as President Franklin D. Roosevelt famously said, “Repetition does not transform a lie into a truth.”

Sooner or later, it all comes toppling down.

The December edition of InMaricopa Magazine is in Maricopa mailboxes and available online.

![City gave new manager big low-interest home loan City Manager Ben Bitter speaks during a Chamber of Commerce event at Global Water Resources on April 11, 2024. Bitter discussed the current state of economic development in Maricopa, as well as hinting at lowering property tax rates again. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-041124-ben-bitter-chamber-property-taxes-web-218x150.jpg)

![3 things to know about the new city budget Vice Mayor Amber Liermann and Councilmember Eric Goettl review parts of the city's 2024 operational budget with Mayor Nancy Smith on April 24, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-042424-preliminary-budget-meeting-web-218x150.jpg)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)