Brian Simmons died at his Villages at Rancho El Dorado home on Aug. 29 during an interaction with Maricopa police that started as a noise complaint and ended in a shootout.

Brian was 38. He spent the last 20 months of his life as a resident of Maricopa, battling mental-health issues that likely stemmed from an exposure to weapons-grade plutonium more than a decade earlier, an event many in his family regard as the day Brian really was killed.

From that point, Brian found trouble at each step in his life. After radiation exposure at the Idaho National Laboratory, his mental health seemed to decline.

He moved to Maricopa from Idaho Falls to build a business selling solar panels only to have his partners leave with all the money he’d put into it, according to his father, Hal.

A man with mental-health problems, Brian moved to one of the states least capable of giving him the help he needed.

According to the United Health Foundation and Mental Health America, the Grand Canyon State is ranked 46th in the United States for access to mental-health providers.

The final blow came on that hot August day when Brian’s lifeless body lie in the side yard of his home with wounds from six gunshots and more from fierce bites by a K-9 unit.

So, you might ask, how does Brian’s story end in such a horrid manner?

It’s best to start at the beginning.

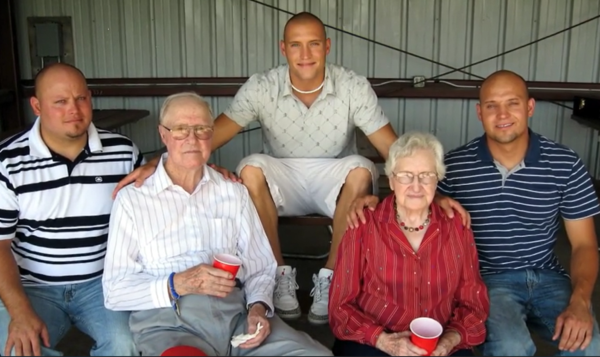

Growing up in Idaho Falls, Brian played multiple sports and was the prototype of an All-American boy. He was athletic, attractive, witty, intelligent.

Brian excelled in basketball. When his high school team, the Hillcrest Knights, played, it was an event not only for the Simmons family but for the entire community. They all wanted to see the next feat Brian had up his sleeve. He was the kind of player who could put the team on his back and take over a game. He also enjoyed baseball, golf, riding snowmobiles, along with hunting and fishing.

He was a prankster, who came up with nicknames for everyone, his father, Hal, explained.

“He was a friend to everybody,” Hal said. “I mean, he always teased everyone. Him and his brother Justin would come up with nicknames for everyone. They called my wife Cheryl, ‘Hernando Helmetron.’ They had all sorts of names. They’d call me ‘Bean’ and it was all goodness. It was never belittling anyone, just good fun.”

Hal remembered a time Brian got in a little hit of good-natured trouble.

Brian obliged, telling the woman the sale would help with his troop’s programs. He couldn’t close the sale on the first try, so Cory and his friends egged Brian on to just give the pizza to the woman.

After the woman opened the box, Hal said he and his wife heard about it.

“That woman called us screaming all these obscenities,” Hal said. “I couldn’t let Brian see it but I couldn’t stop laughing. It was so funny. It was just kids being kids.”

There was a softer side to Brian that he hid from people, as Hal explained.

Soon after graduating high school and returning from a mission in Tallahassee, Fla., for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Brian was hired at the Idaho National Laboratory in 2004, which at the time, provided some of the best-paying jobs to be found in Idaho Falls.

The exposure

Brian met Ralph Stanton when they were hired as security guards at INL and the two became fast friends. Three years later, they moved up the ladder at the facility, owned by the Department of Energy and operated by Battelle Energy Alliance, and were hired as Nuclear Facility Operators at the plant’s Zero Power Physics Reactor Facility.

Years down the road, they would take a trip to hell and back together. As Stanton recalls, it started on Nov. 8, 2011, when Brian and Stanton were exposed to weapons-grade Plutonium 239 and Americium 241, both highly radioactive substances.

This would be the date that family members believe Brian was handed a death sentence. Video of the moment of Brian and Stanton’s exposure can be found online.

Brian and Stanton were part of a 16-member crew, which was to repackage a Plutonium 239 stainless-steel-clad plate from a clamshell container, place it in a can and repackage it in a drum to be sent to another Department of Energy site.

As Stanton and Brian expected, disaster struck. The clamshell containing the radioactive plate was compromised. When Stanton opened it, the appearance of black powder, a result of oxidation of the plate, meant that everyone in the room that day was exposed to differing levels that could cause radiation poisoning.

“When I opened it, Brian said, ‘We’ve got powder. I hope that wasn’t what I thought it was,’” Stanton said.

Unfortunately, Brian was right.

His and Stanton’s lives were never the same.

Living with a new reality

According to the Mayo Clinic, the physical symptoms of Acute Radiation Sickness include nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, headache, fever, dizziness and disorientation, weakness and fatigue, hair loss, bloody vomit and stools from internal bleeding, infections and low blood pressure — many of which Brian and Stanton experienced.

Stanton said they had extreme fits of bloody diarrhea and vomited blood.

“You could tell that the radiation was killing us from the inside,” Stanton said.

As the years passed, mental symptoms from the exposure also became apparent.

In 2019, Stanton was diagnosed with severe depression.

“It’s a lot more than one day you wake up and you have the blues,” Stanton said. “It’s debilitating. It was a lot worse than I would have ever imagined.”

A few months before his untimely death, Brian reached out to Stanton.

“He wanted me and my wife to come down to Maricopa and help him put on a show,” Stanton said. “He offered to put us up and pay us $10,000 each. But we couldn’t make sense of it. Brian had a quick wit, but he wasn’t a comedian, and we knew that there wasn’t a show planned.

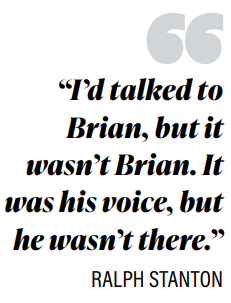

“I’d talked to Brian, but it wasn’t Brian. It was his voice, but he wasn’t there.”

Stanton had spent countless hours educating himself on radiation exposure and reached out to a doctor he’d been seeing to ask about Brian.

In 1986, two massive explosions at Chernobyl, a Russian nuclear power plant, killed 28 people and left thousands sickened from cancer and other conditions from the fallout.

As the years passed, mental illness from the disaster also became a concern. In fact, the Chernobyl Forum, a conglomeration of United Nations agencies founded in 2003 to scientifically assess the environmental consequences of the disaster, concluded that mental health was the largest public-health problem unleashed by the accident.

In 2000, Ukrainian researchers Dr. Konstantin N. Loganovsky and Dr. Tatiana K. Loganovskaja conducted a study of workers who performed cleanup duties at the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone from 1986 to 1991. They found those people were five times more likely to have schizophrenia disorders than the public in Ukraine.

Additional studies show those exposed at Chernobyl also were at a significantly higher risk of developing other psychological conditions, including anxiety or depression.

A downward spiral

Was Brian, in fact, schizophrenic at the time of his death? The answer to that question will never be known.

Brian was a strong-willed man determined to live life on his terms. As his father, Hal, explained, those terms were becoming more and more difficult for those close to him to embrace with each passing day.

Hal made the trip down to Maricopa in February of 2022 to visit his son, and while the two were talking, Brian started fighting with Hal. A family member stepped in to pull Brian off his father.

Hal was upset at Brian’s actions, but he had no desire to file charges.

“We were in the truck together and I said something that Brian didn’t like, and he jumped over the console and started beating on me,” Hal said. “It was a scene, and a passerby called the law and before we could get out of there, they were onsite.”

Being that Hal was Brian’s father, it was a domestic violence incident, which meant the officer could press charges. Brian went to jail for 10 days. Hal filed for a Title 36, or a 72-hour hold for a psychiatric evaluation for his son. It’s an involuntary process for care and treatment of those with a mental disorder. It was a father’s attempt to get help for his son.

“I told everyone who would listen that Brian needed a brain scan or something,” Hal said.

“I told everyone who would listen that Brian needed a brain scan or something,” Hal said.

While Brian was in jail, Hal saw Brian’s living conditions at home.

“His house was awful,“ Hal said. “The Brian I knew was obsessed with being clean and organized. Before he’d moved to Maricopa, he’d get in my truck and ask me, ‘Dad, why do you have all that crap in here? Clean it up!’ He didn’t like any kind of mess in his house or in his vehicle.”

Hal said he arranged to get Brian’s home cleaned. For two days, four professional cleaners and a friend of Brian’s worked on the inside and outside of the home.

The effort was massive, but once Brian got back in the home, he wasted little time getting it back to a disorganized, cluttered state.

When Hal was back in Maricopa six months later to take care of Brian’s final affairs after his death, he couldn’t tell that the house had ever been cleaned.

“It was worse than it was … the first time,” Hal said.

Coming to Maricopa

Brian moved to Maricopa in January 2021.

“He told me that he met a couple, and they were all going to move to Arizona to sell solar panels,” Hal said. “The couple had moved down there a few months earlier.”

It didn’t take long for life to start falling apart for Brian in the desert.

Hal said that after six months, the couple vanished and left Brian high and dry. Hal believes they may have taken Brian for as much as $200,000.

“I’ve got a cousin that’s a lawyer who is working to get all of Brian’s bank statements from Chase and we’re trying to figure out what happened there,” Hal said.

In 20 months, Brian had 22 documented interactions with MPD, according to documents obtained by InMaricopa. Among them was Brian trying to file charges alleging his property had been stolen.

His first brush with the law came in March, 2021 at a routine traffic stop, where he was found to be driving on a suspended license.

The next was in January of 2022 — meaning his final 21 episodes with police were compressed within an eight-month period. There was an arrest in February of 2022 by the Chandler Police Department, where they found Brian driving a borrowed car with 13 guns and rifles. There was no additional information available about who owned the firearms.

On one call, Brian wanted to file a report that his car had been stolen. The officer on duty told Brian that his car was impounded and gave him the lot where it could be found. The report pointed out that Brian’s car had been abandoned alongside the road prior to being impounded by DPS.

Another time, Brian was charged with a misdemeanor on electronic communication of threats. In that investigation, Brian told officers he’d been robbed of $100,000 in goods and cash while trying to help people he’d met.

There were also a couple of calls involving Brian making threats, trying to get people to return goods he’d gifted them. On one call, he said he’d given away $1 million in gold, cash and Michael Jordan sneakers and wanted them back.

During one incident at Desert Financial inside Fry’s grocery store, reports state he tried to jump over the desk and assault a bank teller but was thwarted by a plexiglass barrier.

In the final month of Brian’s life, there were six calls leading up to the day of his death.

One involved a noise complaint in which he claimed he was working on a movie and gave the police the gift of a pair of cowboy boots made for UFC fighter Connor McGregor along with a box of bullets.

In another incident, he took off his shirt at the intersection of John Wayne Parkway and Honeycutt and threw it into oncoming traffic. When officers arrived, he ran from them, giving them the finger and running to his house. There was a criminal trespass charge for crossing Union Pacific Railroad tracks in an unauthorized area. The same report states that police officers watched Brian run into his house, but opted not to confront him that night, “due to Brian’s history of violence and his agitated state.”

It was clear to Maricopa Police officers Brian had mental health issues. Many of their reports obtained by InMaricopa noted that.

In addition, Hal and Cory, Brian’s brother, say they communicated those concerns to MPD officers. Both saw disaster on the horizon and were trying to do whatever they could to avert it.

On Aug. 13, about two weeks before his death, a call was made to Brian’s residence after he posted images of firearms tied with shoelaces on Facebook. At the behest of Brian’s brother, Cory, a crisis worker came by Brian’s residence with four officers. Brian refused to talk with the worker about mental-health issues. Instead, he gave pairs of shoes to each police officer and the crisis worker.

“I actually called the cops to help me get a crisis team there on the 13th of August,” Cory said. “And it was a completely wasted effort for what went on that night. We asked for the cops’ help. We pleaded with them to try to get us some help. We didn’t know what to do. He’s an adult.”

The police also saw trouble coming.

“Two days before they shot and killed him, they called me and said, ‘Your brother says you’re coming to get him. Are you coming to get him?’” Cory recalled. “And I said I’d been talking to him. He would answer the phone and then he wouldn’t. It was really sporadic to be able to talk to him and I said, ‘Whatever you do, please don’t kill my brother. We’re trying to get him help.’ They kept telling us the wrong officer would shoot him if he got too aggressive.”

Even when it’s apparent to everyone else that someone is dealing with mental-health problems, it’s difficult to get that person help if they don’t want it, as in Brian’s case, according to family members.

Making it more difficult is that Arizona ranks at the bottom of the country when it comes to mental health providers. Mental Health America, in its 2022 report, ranked Arizona 46th in access to mental-health providers. Another part of the same study that examined the overall population in need of mental-health care, patients with unmet needs and the size of the mental health workforce, ranked Arizona 49th.

Brianna Reinhold, the owner of Northern Lights Therapy in Maricopa and a licensed professional counselor, put it this way:

Reinhold pointed out that there’s an intersection between personal freedoms and getting people help that must be balanced.

“If you have anybody over the age of 18 that needs services, most providers are going to say that person needs to reach out to us directly because they’re a legal adult,” Reinhold said. “So, you’re going to start to get push back as it is, if you can get them into a facility.”

Months earlier, Hal made the effort to get Brian help when he had him committed for 72 hours, but Brian learned from the situation and effectively cut his family off afterward.

“I was out to dinner one night with some people, and I got a phone call, and I didn’t recognize the number, so I answered it and it was Brian and he says, what are you doing Dad? I said, ‘Well, I’m in Texas Roadhouse,’” said Hal, who was eating with five other family members.

“And he says, ‘Oh, well, real good. I’m in here with all these crazy people,’” Hal recalled. “And anyway, he just went off on me and said, ‘I’ll never talk to you again,’ …that’s how bad he was. And, I just had to hang up on him because everybody at the table could hear and the phone wasn’t on speaker. That’s really the last time I talked to him. He did text me back and say that I love you. But that’s all I got back from him. He was not in a good place.”

Sometimes, as Reinhold explained, people who need help but don’t want to face that fact figure out how to game the system.

It creates a situation where mental health professionals must try to hit a moving target.

“All they have to go off of is what’s happening in front of them in the moment,” Reinhold said. “This is where our system is going to fail people, because those that need it, if they know how to play the game well enough or they’re intelligent enough, they’re going to say the right things and are going to get themselves out.”

Brian had figured out the system. If he didn’t say anything, they couldn’t do anything.

When the police and the crisis team got back to Cory after that visit with Brian on Aug. 13, there wasn’t a lot to report.

“They called me back and said, ‘We can’t really tell you a lot because of HIPAA, but he didn’t display anything that could allow us to arrest him to get him in to get him some help,’” Cory said.

Families trying to help their adult children are going to face difficulty. Being out of state compounds that difficulty.

“If I had to help a grown child in another state, I wouldn’t even know where to start,” Reinhold said. “The laws are different everywhere and I know the laws in Arizona, but I’d be at a disadvantage in another state.”

The day it all ended

In a copy of the final investigation by the Pinal County Sheriff’s office obtained by InMaricopa, Brian told officers the day of his shooting – an interaction that started as a noise complaint – that he’d been up all night crying and started the interaction with smiles, fist bumps and hugs with the responding officers, who knew him by name.

But as the officers asserted themselves and asked Brian to turn his music down, the temperature of the interaction changed. Brian went from friendly to hostile.

Officers’ body-worn cameras of the incident show it all change in an instant.

Brian sat down in a lawn chair in his driveway and produced two handguns, which he later put down and followed up by brandishing a hatchet.

In the video footage, police can be heard yelling at Brian to put down the guns, then the hatchet and later shouting commands at him to get on the ground.

He responded with multiple obscene hand gestures and can later be heard telling officers, “I’ve got a bigger voice than you.”

After the police fired a shot of non-lethal force, essentially a bean bag, to get Brian to comply with their commands, the interaction got worse. Brian started walking to the carport and back into his house.

Then, according to the investigation report and video footage, said, “You’re ——ing done mother———-,” which led to another shot of less lethal force.

Brian walked backward into his house where officers feared he had more weapons and ammunition, which the PCSO’s investigation confirmed.

Brian retrieved a 12-gauge shotgun from his house, sought cover from behind a cinderblock wall in his side yard and fired a round of birdshot at police officers. Officers returned fire, killing Brian.

According to the Pinal County Medical Examiner’s report, Brian was shot six times. He suffered two bullet wounds to the chest cavity that damaged multiple vital organs and another to the back. He also suffered multiple dog-bite wounds from a K9 unit.

Looking for answers

The shootout, a block from Butterfield Elementary School, demonstrates the dangers of untreated mental illness.

Brian’s 21 prior interactions with police highlight the inadequacies of Arizona’s mental health and legal systems that left Brian’s family helpless.

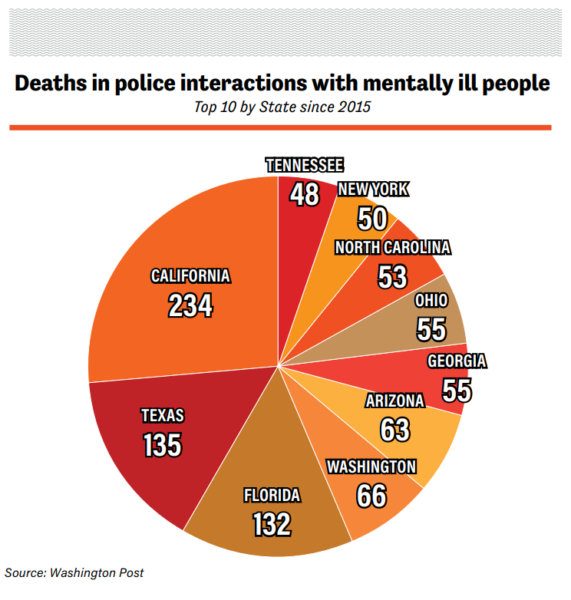

Brian’s story, unfortunately, isn’t all that unique. The Washington Post curates a database of police-involved shootings that dates back to 2015. Nationally, there have been 1,695 shooting deaths by police during interactions with mentally ill people, which accounts for roughly 21 percent of all police-involved shooting deaths.

Arizona is fifth on the list with 63. California leads the way with 234.

The issue of mental illness and policing is of growing concern. Studies done as recently as 10 years ago estimated that 1 in 10 police interactions were with mentally ill subjects.

Michael Scott, director of the Center for Problem-Oriented Policing and a clinical professor in the School of Criminology & Criminal Justice at Arizona State University, recently analyzed data with the Phoenix Police Department concerning mental illness.

“The frequency with which police officers are encountering people with mental illness does appear to be on the rise,” Scott said. “I recently did some work with the Phoenix Police Department in reviewing some of their data and we estimated that mental illness may play a factor in as many as one call in every eight. And that’s a lot of interactions.

“Most of those interactions are going to be resolved peacefully. The mental disorder may not be acute: It’s not serious, it’s not dangerous. It’s just a person having some difficulty. But it does necessarily increase the probability that at least some of those encounters and more of them will be high risk.”

In a September interview with InMaricopa during his final days as Maricopa’s police chief, James Hughes wouldn’t speak directly about the situation with Brian, but Hughes said he believes that dealing with all people effectively — including those mentally-ill – is part of their job.

“They are social problems, mental illness and homelessness,” Hughes said. “Often those calls happen during hours when the city is closed. So, who gets the call? The police.”

Hughes pointed out that many times, the police know these people and can offer important background.

“I think the police should still be involved in some of those people-related things,” Hughes said. “If you’ve engaged with the community, you know who Joe is and what his problems are. He may be a veteran who maybe served his country and was injured and is having some problems.

“Yet when you have a 25-year-old police officer who is trained in compliance with patrol and he’s saying, ‘Get your hands out of your pocket! What are you doing here? No, you can’t go to the bathroom,’ it’s not going to end well.”

Scott agreed that tone, when dealing with someone with mental illness is important.

“Once the police officers have the sense of whether this person has some kind of a mental disorder, then it’s usually advised that police officers not resort to barking, or shouting commands, which they normally would do if the person was completely mentally fit,” Scott said.

“The police might use aggressive language, assertively giving commands in a very loud and authoritative voice. But that often is counter-productive in dealing with a person who may be suffering some form of mental disorder. It can be disorienting to the person. They may not be able to follow the commands, it can be intimidating, they could actually escalate the tensions rather than de-escalate them.”

Hughes said that whenever possible, it’s a good idea to keep the situation light.

“We’ve done a good job teaching officers that if you ask these people to do the same thing six times, the seventh time is not going to be the magical response,” Hughes said. “Re-evaluate what you’re doing. Inject a little humor or take a different approach. That’s how you de-escalate.”

Prior to becoming a counselor, Reinhold served in the criminal-justice system as a detention officer and worked with the Glendale Police Department as a volunteer, offering peer support for officers in officer-involved shootings and deaths in the line of duty. She believes that for the most part police officers are often thrust into an impossible situation.

“And then, we need a secondary source for callouts once they’ve identified that it’s a mental-health issue. How can we include local resources or their own team, that’s staffed with mental-health providers to help in those situations? That’s really what every agency needs.”

Monica Williams, public information officer for Maricopa’s police, fire, and emergency management, said training for Maricopa’s police officers is ongoing.

“The city of Maricopa Police Department’s officers participate in de-escalation and crisis intervention training prior to their initial field duty and repeat the training annually,” Williams said. “Those trainings ensure our officers understand how to approach a range of dynamic scenarios and begin a dialog with individuals in crisis. The primary goal is to ensure the public and our officers are safe, while de-escalating situations.

“Our department has designated Crisis Intervention Specialists, who are officers who have elected to participate in further training beyond the annual requirement for all officers.”

Those officers are liaisons with community partners that provide resources, such as mental-health counseling, substance-abuse treatment and shelter space to those in crisis. While the Police Department does not directly provide the resources, according to Williams, officers are equipped to connect individuals with mental-health resources or other resources they need, including Community Bridges Inc., Horizon Health & Wellness, La Frontera Impact & Maricopa Behavioral Health Services.

Remembering Brian

It will take years for the Simmons family to recover from losing Brian twice, first to radiation poisoning and later to the exchange of gunfire.

“I feel like I lost my best friend,” Cory, Brian’s brother, said. “We did everything together. But after the exposure, Brian changed. He cut himself off from the family. I couldn’t understand it. He loved snowmobiling and then he’s telling me that he can’t stand the cold and wants to move to Arizona? I didn’t know what to think.”

Cory said that prior to the exposure, Brian had the world at his feet.

“He could get any girl,” Cory said. “He could play any sport. He was smart and funny. He was talented in every way, shape, or form. He was everything under the sun and then some — and absolutely taken down in his prime.”

Cheri, Brian’s sister, said he became an older brother to her sons. She was 10 years older than Brian.

“I got married kind of young and started having kids and my boys were really close with him,” Cheri said. “They liked to hang out with him, and he was really good to my kids. He would play basketball with them, take them places or he would play video games with them. He’d always buy the newest game. So, they love going to play with him. He would take them out to eat and just go do things with them because they were kind of, like, his little brothers in a way.”

“He just changed,” Cheri said. “He struggled with things, he started pulling away from people and kind of isolating himself. He didn’t want to be around everybody as much and he was stressed out because he was going through a court case, and he just changed.

“He started worrying about things that he never worried about before.”

That, in turn, caused Cheri to worry about him.

“I always kept trying to call him,” she said. “We were trying to get him some help, but we didn’t realize all of the effects that had happened to him, the schizophrenia from the radiation. We didn’t realize that’s what it was.”

“I was plumb stupid about the effects of the radiation poisoning and mental health,” Hal said. “I didn’t realize what was going on until I talked to Ralph. When we started talking, everything started making sense.”

Hal and Stanton hadn’t talked that often before Brian’s death, but curiosity and a hunch led the two to see if Brian had any other answers to share from the great beyond.

Brian was cremated and his ashes were at the wake held the night before the funeral. Stanton and his wife, Jodi, were on hand.

“An hour before that started, I got a radiological device from one of my friends,” Stanton said. “And I talked Hal into taking Brian’s ashes into one of the back rooms. I took a scoop like, you know, like laundry-detergent scoop, off the top of his ashes, put it on a piece of paper.”

The device perked up as Stanton took a radioactivity reading.

“And his ashes were still (radioactive) hot.”

Correction: An incorrect number of shots fired by Brian Simmons during an altercation with Maricopa Police on the day of his death was reported in the March InMaricopa magazine. The correct number was one.

![City gave new manager big low-interest home loan City Manager Ben Bitter speaks during a Chamber of Commerce event at Global Water Resources on April 11, 2024. Bitter discussed the current state of economic development in Maricopa, as well as hinting at lowering property tax rates again. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-041124-ben-bitter-chamber-property-taxes-web-218x150.jpg)

![3 things to know about the new city budget Vice Mayor Amber Liermann and Councilmember Eric Goettl review parts of the city's 2024 operational budget with Mayor Nancy Smith on April 24, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-042424-preliminary-budget-meeting-web-218x150.jpg)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)

![City gave new manager big low-interest home loan City Manager Ben Bitter speaks during a Chamber of Commerce event at Global Water Resources on April 11, 2024. Bitter discussed the current state of economic development in Maricopa, as well as hinting at lowering property tax rates again. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-041124-ben-bitter-chamber-property-taxes-web-100x70.jpg)