You can’t see it, but you can feel it. It’s a visceral reaction.

Like your body knows what lies inside those thick plastic bags on cold metal tables when you step into the freezer at the Pinal County Medical Examiner’s Office.

A foul, almost sickly smell hits the nose just after the puff of icy air. It causes your chest to tighten, your heart rate to jump and the hair to rise on the back of your neck.

This is where the medical examiner keeps nearly two dozen unidentified remains, each simply labeled with a case number. They were given a name at birth. They yearn to be given a name in death.

Who are they? What brought them into the desert only to die alone and unknown?

That’s an answer PCMEO medicolegal investigator Suzi Dodt hopes to find after she received a $500,000 grant from the National Institute of Justice, an arm of the U.S. Department of Justice.

But she has her suspicions.

“We think that most of our skeletal remains are migrants,” Dodt said.

Pinal County has 147 unidentified persons cases, about 20 of which are stored in bags and boxes inside the medical examiner’s freezer. Of those, 18 are suspected to be undocumented migrants from Mexico and other Central American countries.

“They were found in areas where migrants typically are known to cross,” Dodt said. “The belongings with them tend to be Mexican pesos, non-traceable cellphones, water jugs, camouflaged backpacks and clothing items. And they’re all skeletal.”

Borderlands

Experts say there are migrant corridors a “stone’s throw” from Maricopa, weaving through the mountains and brush flanking Thunderbird Farms and Hidden Valley.

A surge occurred last year with border crossings when the Biden Administration lifted Title 42, an immigration policy re-established during the pandemic to limit the spread of the disease.

In its most recent quarterly report, U.S. Customs and Border Patrol said it processed more than 629,000 people at the border — as many people as live in Boston. This included more than 219,000 processed in Arizona.

Around that time, towns and cities like Bisbee and Casa Grande reported seeing higher numbers of undocumented migrants released when seeking asylum from their home countries, with Casa Grande estimating hundreds of drop-offs weekly.

Pinal County Sheriff Mark Lamb said he has helped carry the bodies of migrants he found dead.

“A lot of the times we land or hoist them up into the helicopter and fly them to one of the border patrol stations and turn them over,” he told Feb. 14.

Humane Borders Board Chair Laurie Cantillo believes there is an element missing from the story.

“There’s so much noise about the politics of the border, but so little being said about the men, women and children dying out there,” she said. “There’s much more at play than politics. It’s about humanity.”

The journey

Humane Borders asserts the trek from Nogales to Tucson alone could take a person about five days of walking and most are grossly unprepared.

Cantillo said while migration in the Southwest has traditionally consisted of working aged men from Mexico and Central America, the number of families with kids crossing the border has grown exponentially.

“Recently, we have encountered many more families than usual from 18 different countries,” she said. “Many were assaulted or robbed along the way and yet, still, they want to come here because they are fleeing violence, oppression and poverty in their home countries.”

Each of the more than 629,000 encounters were processed under Title 8, a decades-old immigration law that includes swifter, stricter deportation measures, but also allows for a larger number of asylum and refugee seekers to enter the country.

For many, the journey was long and traumatic.

“One thing we observed is migrants are often lied to by smugglers — coyotes, as they’re known — about how easy the journey is going to be,” Cantillo said. “They may show up wearing sandals or kids in crocs or people pushing baby strollers through thorn-scrub because they were told it was just a 30-minute walk.”

And that ill-preparation can lead to devastating consequences.

Mapping death

“Dying alone in the desert of heat stroke is a horrible, horrible way to die,” Cantillo said.

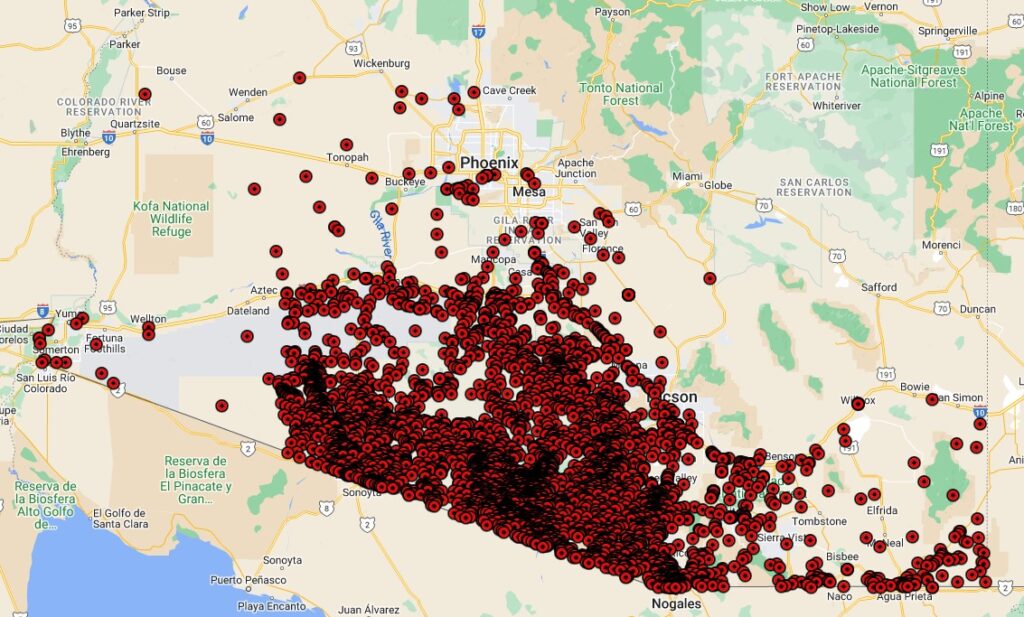

Aside from providing safe water stations to migrants, hikers and hunters throughout the Sonoran Desert, Humane Borders also publishes a migrant mortality map on its website.

There, visitors encounter a sea of red dots strewn across southern Arizona and extending north of Phoenix.

Each of the 4,177 dots is a case of a migrant’s body found over the last four decades, regardless of whether they were identified. Pinal County has the third-most with 288 cases reported since 1990.

Some causes of death in the desert are obvious: dehydration or overheating. A surprising number died by drowning, likely by attempting to drink from or cool down in a canal.

And others are suspicious. Blunt force trauma, multiple gunshot wounds and asphyxiation.

That was the case with Jesus Anaya Longoria who, at age 30, was found dead from multiple blunt force injuries near Amarillo Valley and Papago Roads in Thunderbird Farms in 2007.

Or a group of 21- to 40-year-old men found dead from multiple gunshot wounds in the chest and abdomen along Interstate 10 in 2003.

But so many are labeled with a case number and two words: “unidentified, undetermined.”

That is where the medical examiner and other players get involved.

Bones and dirt

These local cases of unidentified remains often play out like the opening scene of a Law & Order episode.

Hunters, hikers or ATV riders stumble across skeletal remains during an outing in the desert. They rarely encounter a complete skeleton or a decomposing body because of the harsh climate.

Instead, skulls, femurs or other bones are found scattered near remote trails, in dry washes or along roads.

The remains are reported to local law enforcement, which initiate the investigation and turn it over to the county medical examiner.

PCMEO contracts with cities and towns across the county as well as with the Gila River Indian Community, but not with the Ak-Chin Indian Community.

It begs the question of why — as of publication time, Ak-Chin member Joy Antone is still missing after nearly two months. She went missing Jan. 8 but Ak-Chin Police Department didn’t notify the community until Jan. 26.

Ak-Chin spokesperson Matthew Benson did not respond to several requests for comment.

These are the situations PCMEO wants to avoid.

“We bring everything found at the scene back to the office,” Dodt said. “We’ll search the clothing to see if there’s anything in the pockets, in the waistband, sewn into the clothing, anything like that. We try to find anything that can lead to an ID.”

These clues aren’t always present, and when they are they are usually worn and weatherbeaten.

Ripped, faded clothing or a work boot caked in dirt. A ripped paystub. A child’s folded drawing yellowed by the sun.

Sometimes, there’s nothing left but bones and dirt.

Forensic files

When the initial search doesn’t turn up any information, forensic anthropologist Courtney Koppenhaver-Astrom steps in.

“When looking at the skeletal remains, I’m trying to assess whether or not the person was male or female, how old they were, how tall they were, their ancestral background,” she said. “But then, also, is there any trauma, any signs of disease on the bones, missing teeth, anything that can be identifying.”

That process can take several hours.

From there, a biological profile is created and eventually entered onto the DOJ’s National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, better known as NamUs.

Unfortunately, that’s where many cases go cold.

While there is a national database maintained by the FBI for fingerprints, none exist for dental records or even DNA.

“Dentists are only required to keep their records for seven years,” Dodt said. “Also, we have databases where DNA can be put into, but it’s not like everyone’s DNA is magically there.”

Often, the only reason a DNA sample may exist is if a family member submitted DNA for testing or if a person with a criminal record already had their fingerprints and DNA logged.

When DNA is obtained, analyzed and still turns up nothing, an investigative genetic genealogist may take the helm.

Last resort

Cairenn Binder has worked with DNA Doe Project and Coast to Coast Genetic Genealogy Services for years to help solve cases of unidentified remains across the country. For some of the hundreds of unidentified deceased in Pinal County, she’s the last resort.

It can be like finding a needle in a haystack. But she’s done it before.

“The DNA profile is uploaded to two databases, and I get two outputs: an ethnicity report of some sort and a genetic match list,” she said.

From there, Binder can begin to build a family tree.

“Usually, we’re looking at third, fourth and fifth cousins,” she said. “We have to build out the genetic match’s family tree to find connections and eventually figure out who the person is we’re trying to identify. It could be less than a day, it could take months or years.”

While obtaining a usable DNA profile used to be the biggest obstacle, rapid scientific advancements have changed that. Instead, the bigger challenge these days is having enough profiles to match against.

“The databases we use are made up of mostly western Europeans and Caucasians,” Binder said. “When you get into minority populations, it can be very, very difficult or even impossible to identify the subject.”

Investigative genetic genealogists like Binder cannot use genetic profiles found on most consumer databases like 23andMe. Instead, they rely on the public to upload that information to the two databases they can use: FamilyTreeDNA and GEDmatch.

“It’s the most common misconception,” she said. “If every person that wants to see these cases solved would upload their DNA, we would solve so many more.”

‘Silent mass disaster’

This summer, PCMEO plans to use its new grant money to start the process of identifying its frozen remains. Over the next two years, the office will collect DNA samples from family members of missing persons via law enforcement and foreign consulates.

Each DNA analysis begins at $1,800 and can extend beyond $15,000 for forensic genealogy for addition testing, according to Dodt. That’s why the half-million-dollar grant is so important.

Everyone involved in solving unidentified and missing persons cases — from the officers who initially investigate cases to the investigative genetic genealogists like Binder — cite the importance of identifying remains.

“Some people have called unidentified remains a silent mass disaster,” Binder said. “We think about missing people all the time. Well, unidentified remains are the answers to missing people cases and their families are missing them.”

For forensic anthropologist Koppenhaver-Astrom, it’s about helping families.

“Helping families is the most important thing even if that’s just providing answers for what happened,” she said. “We deal with all sorts of death, that’s literally the job description. But we’re also here for the living as much as we are here for the dead.”

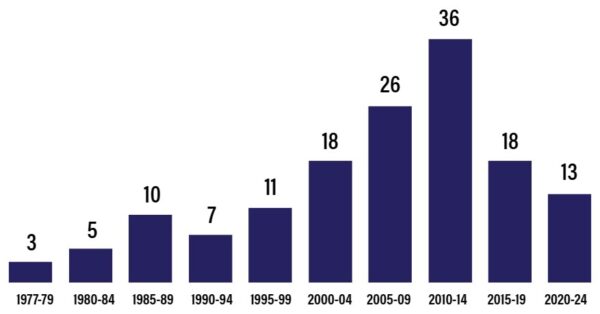

47 years of unidentified bodies in Pinal County

Records for Pinal County’s long-term unidentified persons cases began March 4, 1977, with the discovery of partial skeletal remains found in a desert wash. Since then, the county has documented 147 cases still pending identification.

Before 2017, the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office handled local cases, which is why Pinal County currently only has 20 unidentified remains in its office.

Here’s a look at the number of unidentified cases over the years.

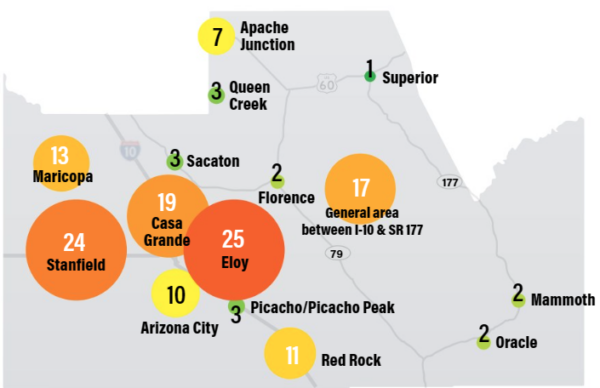

Who are Maricopa’s unidentified persons?

Thirteen unidentified persons cases are active in and around Maricopa. Nearly all of them are Latino men between the ages of 15 and 50 found in the desert, in washes or near roadways between 1983 and 2021.

The three most recent cases — remains found from February 2019 to January 2021 — are all suspected by a county forensic anthropologist to be from the same person.

Details about each case, including circumstances, available physical descriptions, evidence photos and specific locations, can be found at NamUs.gov.

Missing and murdered

Missing and murdered Indigenous people have made headlines in the U.S. and Canada in recent years, particularly women and girls. Some call it a crisis based on centuries of violence and disenfranchisement.

The U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs reports more than 84% of American Indian and Alaska Native women have experienced violence in their lifetime. But the numbers of those who went missing are underreported and vary widely across platforms.

For example, BIA lists 33 Indigenous people missing across the country, including five in Arizona, on its missing and murdered cases website. However, the department also estimates there may be as many as 4,200 missing and murdered cases that have gone unsolved.

The National Missing and Unidentified Persons System cited 853 missing Indigenous people across the country as of mid-February. In Arizona, 83 went missing from 1956 to 2023. In Pinal County, six.

Meanwhile, social media posts about missing children and adults proliferate on dedicated pages like “Indian Country’s Missing” or “MMIP in AZ & NM.” Updates on those found safe aren’t always provided.

Helpful websites

DNAsolves.com – Allows users to contribute DNA to a national database to help solve John and Jane Doe cases

GEDMatch.com – Allows users to contribute DNA to a national database

NamUs.gov – A national database and resource center for missing, unidentified and unclaimed persons cases across the country

HumaneBorders.info – Interactive migrant mortality map

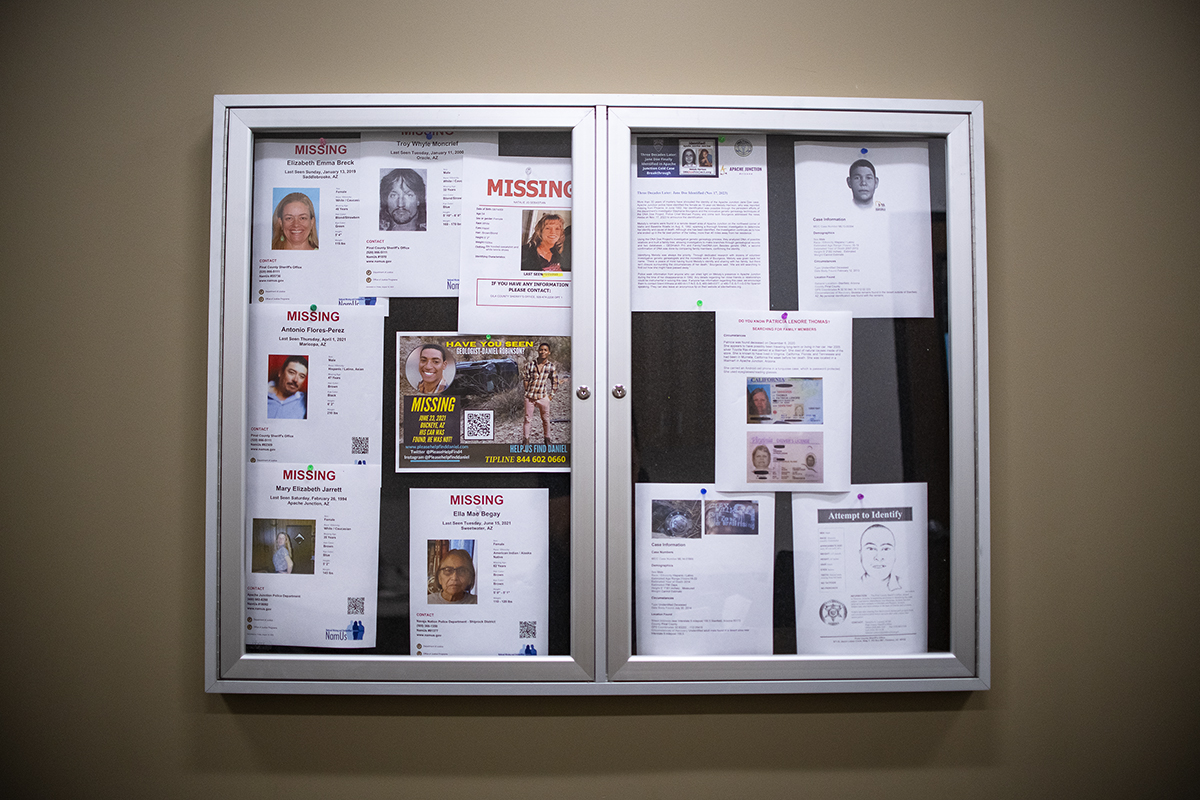

![spencer-020624-pinal-county-medical-examiner-unidentified-01 Photos, news headlines and other memorabilia are pinned to a board in Senior Medicolegal Investigator Suzi Dodt's office at the Pinal County Medical Examiner in Florence on Feb. 6, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/spencer-020624-pinal-county-medical-examiner-unidentified-web-01-1068x712.jpg)

![Photos, news headlines and other memorabilia are pinned to a board in Senior Medicolegal Investigator Suzi Dodt's office at the Pinal County Medical Examiner in Florence on Feb. 6, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/spencer-020624-pinal-county-medical-examiner-unidentified-web-01.jpg)

![City gave new manager big low-interest home loan City Manager Ben Bitter speaks during a Chamber of Commerce event at Global Water Resources on April 11, 2024. Bitter discussed the current state of economic development in Maricopa, as well as hinting at lowering property tax rates again. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-041124-ben-bitter-chamber-property-taxes-web-218x150.jpg)

![3 things to know about the new city budget Vice Mayor Amber Liermann and Councilmember Eric Goettl review parts of the city's 2024 operational budget with Mayor Nancy Smith on April 24, 2024. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-042424-preliminary-budget-meeting-web-218x150.jpg)

![Alleged car thief released without charges Phoenix police stop a stolen vehicle on April 20, 2024. [Facebook]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_5040-218x150.jpg)

![City gave new manager big low-interest home loan City Manager Ben Bitter speaks during a Chamber of Commerce event at Global Water Resources on April 11, 2024. Bitter discussed the current state of economic development in Maricopa, as well as hinting at lowering property tax rates again. [Monica D. Spencer]](https://www.inmaricopa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/spencer-041124-ben-bitter-chamber-property-taxes-web-100x70.jpg)